New Jersey Future Blog

New Jersey Future Provides Direction at Joint State Senate and State Assembly Climate Hearing

August 16th, 2022 by Hannah Reynolds

“As New Jersey works to advance decarbonization and resilience efforts, we must ensure that residents are able to make informed decisions for themselves, and their families, in the wake of growing climate risks,” said New Jersey Future (NJF) Policy Manager Kim Irby, at the August 11th joint legislative committee hearing hosted by State Senator Bob Smith (D-17) and State Assemblyman James Kennedy (D-22) last Thursday. She continued, “New legislation with long overdue reforms would ensure that New Jersey homebuyers, renters, and business owners are fully informed about the ever-increasing risks of flooding so that they can protect their belongings and families.”

Kim Irby and Pete Kasabach (NJF) providing testimony to the joint committee on environment last Thursday. Photo Credit: Hannah Reynolds

Irby’s remarks, accompanied by an introduction and conclusion from NJF Executive Director Pete Kasabach, were part of a joint hearing on the environment and climate change, with representatives from the New Jersey State Senate and State Assembly present. The testimony outlined added costs of the growing threat of flooding for New Jersey homes and communities, before introducing the potential for flood disclosure laws to help inform buyers of risks of flooding associated with the properties they purchase. Presently, Irby informed the committee, flood disclosure laws in New Jersey fall significantly below the nationwide standard. Irby and Kasabach suggested that the legislature take steps to build transparency around flood disclosure, including requiring data to be available surrounding historical flood data, flood projections, and flood insurance status, to name a few. All six official recommendations are listed in NJF’s testimonial, available online.

As NJ grapples with drought and braces for an impending storm season, the joint Senate Environment and Energy Committee and the Assembly Environment and Solid Waste Committee hearing examined an array of legislative approaches to addressing climate change. The testimony on flood disclosure proved to be very timely and important within the broader context of the hearing. Commissioner of the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection Shawn LaTourette opened the meeting with remarks on the growing impacts of climate change and the need for urgent political support to mitigate growing climate risk, including flooding, stormwater management, and rising sea levels. Other environmental advocates presented concerns around coastal resilience and sustainable development in coastal NJ communities. Finally, the legislature heard public testimony on two proposed bills related to renewable energy portfolios and fossil fuel divestment.

The hearing offered an opportunity to address the widespread risks of climate change experienced in New Jersey, and the flood disclosure testimony from NJF staff contributed meaningfully to the diverse dialogue on climate and environmental issues across the state. In all, as Commissioner LaTourette explained, “There is no one silver bullet that will protect every community… There is, however, a network of solutions that will ensure the resilience of our communities and economies in the face of a changing climate.” Improved flood disclosure laws offer one such solution.

Meet New Jersey Future’s 2022 Summer Interns!

August 9th, 2022 by New Jersey Future staff

New Jersey Future’s internship program is developing the next generation of thinkers in smart growth. We offer graduate and undergraduate students the opportunity to assist us with various projects, including research, writing, communications, and administration. We appreciate their wide-ranging contributions! See a list of our previous interns and learn how to apply.

Here is what this summer’s interns worked on, in their own words.

Claire Brennan

Temple University

Field of Study: Journalism

I had the pleasure of working alongside Mo Kinberg and Chris Sturm on the Clean Water, Healthy Families, Good Jobs campaign, working alongside a coalition of environmental, business, and labor groups lobbying for Governor Murphy and the legislature to designate American Rescue Plan (ARP) funds to rehabilitate New Jersey’s outdated water infrastructure.

The beginning of my internship focused on gathering information on municipalities that suffered from combined sewer overflows (CSOs), lead-lined pipes, and drinking water utilities contaminated by forever chemicals called PFAS. This research was used to gauge which legislative districts had the widest array of infrastructure issues, and ultimately, as prep for meetings with the legislators of these districts.

Once much of the groundwork of the campaign was laid, I focused on communicating with endorsing members and alerting them of upcoming events and ways to help advance the campaign. I also reached out to legislators to inform them of issues surrounding New Jersey’s failing utilities, and the opportunity that ARP funds provided to begin fixing them.

While working on the campaign, I’ve garnered research skills, a wealth of knowledge on water infrastructure, and the confidence to communicate the importance of its vitality. I feel privileged to be a part of a campaign to keep people healthy, and to see our coalition’s values reflected in the legislature’s budget.

Aishwarya Devarajan

College of the Atlantic

Field of Study: Human Ecology, Policy

My name is Aishwarya Devarajan, a sophomore at the College of the Atlantic, and an intern with New Jersey Future (NJF). Through my time with NJF I have had the opportunity to interact with many local experts in multiple states to learn about the implementation of green and complete streets. Throughout these meetings, I have witnessed the relentless passion of advocates for complete and green streets, who care about people and the planet. As our streets get more crowded and more polluted, disparities within populations grow, decreasing accessibility within our communities. Complete and green streets are community hubs that bring accessibility, safety, sustainability, stormwater management, and economic benefits. The New Jersey Department of Transportation (NJDOT) has the ability to help these advocates create safe streets for communities to enjoy. NJDOT should incorporate green infrastructure and pedestrian safety measures into state-owned streets, encourage municipalities to implement best practices, and develop new set-aside grants for complete and green streets. New Jerseyans deserve clean air to breathe, safe and accessible streets to get around, and support for local businesses.

Margaux Petruska

Lehigh University

Field of Study: Environmental Policy

This spring, I have been grateful to work as a research intern on the Clean Water, Healthy Families, Good Jobs Campaign for New Jersey Future, under the supervision of Mo Kinberg. Through these few months, I have focused primarily on legislative district profiles and conducting research that was utilized as background knowledge for meetings about the campaign with legislators. I researched information about various NJ districts and learned about their drinking and wastewater infrastructure. I compiled summaries with highlights on problems within districts such as lead service lines, forever chemicals like PFAS, combined sewer overflows (CSOs), and contaminants. Additionally, I delved into data with Jyoti Venketraman separating updated LSLI data into their subsequent utilities. Having just begun my Master’s program, it was incredibly enriching to learn more about environmental and water policies through New Jersey Future while learning about it in my classes. I learned how to work outside of my comfort zone toward a specific goal, such as the campaign.

I am grateful for this opportunity to help me delve deeper into the field of advocacy and the progress it can make, and I hope to continue work as important as this organization does in the future.

Sasha Weber

Barnard College

Field of Study: Urban Studies

My name is Sasha Weber and I’m a senior at Barnard College, where I’m an Urban Studies major with a concentration in Environment and Sustainability. This semester I have been working on the Mainstreaming Green Infrastructure team. Since March 2, 2021, NJ municipalities have been required to utilize green infrastructure as a stormwater management technique on all new public and private developments. My role has been to research municipalities’ updated stormwater ordinances and determine which ones have gone above and beyond New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection’s requirements to protect communities from flooding and pollution. In my research, I have interviewed representatives from several municipalities to learn more about how they developed their stormwater ordinances. I have also explored case studies highlighting these new requirements in action. I have enjoyed learning about how diverse municipalities have used their resources and considerations of ecological conditions to create these new ordinances and I am excited for the future of green infrastructure as a tool for flood and pollution prevention, urban heat reduction, and ecological resilience.

Isabel Yip

Princeton University

Field of Study: English

Through the Princeton Recognizing Inequities and Standing for Equality (RISE) program, I worked with New Jersey Future on the Geography of Inequality project, conducting qualitative analysis by interviewing key figures in New Jersey towns about economic and racial integration. My research focused on affordable housing, zoning, the use of space to bring people together, and the importance of community relationships in places throughout New Jersey. I spoke with mayors, the leaders of community groups, council members, and city planning officials about how New Jersey towns work towards integration and maintain their diverse identities. With New Jersey Future’s director of research, Tim Evans, I created a report compiling my interviews with New Jersey leaders and research into the town’s history, which documented former hindrances to integration like formerly redlined districts, as well as developments like inclusionary housing ordinances. The interviews and research I conducted resulted in a series of recommendations for other places in New Jersey in order for them to become more stably diverse and integrated. I am thankful to New Jersey Future, the Princeton RISE program, the community leaders throughout New Jersey who gave me their insight into integration, and to my supervisor Tim Evans, who heightened my understanding of housing in New Jersey and of how the use of space can contribute to socioeconomic inequality.

Amidst rising pedestrian and traffic fatalities, New Jersey seeks to advance safe street design

July 19th, 2022 by Michael Atkins

Photo Credit: City of Hoboken

Street fatalities are on the rise nationally, and right here in New Jersey. The National Highway and Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) reports that 2021 marked a 16 year high in roadway fatalities. In New Jersey, our streets and roads claimed 699 lives in 2021, with 220 pedestrian fatalities accounting for approximately 30% of those fatalities. This pace shows no signs of slowing this year: “318 people have been killed on New Jersey’s roadways [as of July 2022], already an 18% increase from last year’s historically high rates.” This deadly trend has arisen even as commutes remain disrupted from the coronavirus pandemic, with more people opting out of the daily commute to work from home or remotely. In short, while less driving should be associated with fewer fatalities, we have observed the opposite effect, both locally and nationwide. Even with less car travel overall, the increase in fatalities reveals the need to focus on the development of safe streets in our broader efforts to help people drive less.

This month, Smart Growth America released its Dangerous By Design Report for 2022, which paints a stark picture of our lack of progress on street safety nationally and in New Jersey by delving deep into the 2021 statistics on crashes throughout our roadway systems. The results depict New Jersey as the nineteenth most dangerous state in the United States when it comes to street safety.

Pedestrian fatalities directly relate to street design that prioritizes automobile speeds and places pedestrians and cyclists in conflict with larger, faster, deadly vehicles. Conditions that pose the greatest risks to pedestrian safety include places without sidewalks, crosswalks, street lighting (as is common in areas of South Jersey), or urban areas where pedestrians and cyclists must compete with an array of motorized vehicles along busy city arterials(common in North Jersey). As the report states, “Lower-income neighborhoods are much more likely to contain major arterial roads built for high speeds and higher traffic volumes at intersections, exacerbating dangerous conditions for people walking.” In New Jersey, as throughout the United States, these lower-income neighborhoods are predominantly communities of color facing economic hardship and historic disinvestment.

One commonly dangerous type of roadway found throughout New Jersey is what is known as the “stroad”. The term “stroad” was coined to express the conflict within modern traffic engineering to balance “street” uses, like commerce, temporary parking, and property entrances, with “road” usage, where high speeds are prioritized to connect vehicles between longer distance destinations. Stroads often lack sidewalks and crosswalks, and are particularly dangerous for pedestrians and multi-modal transit users. New Jersey has developed dozens of stroads throughout the state—in part, our famous jughandles are aimed at reducing conflicts on stroads between drivers making turns across oncoming traffic.

Despite the predominance of stroads, not every corner of the state is facing a pedestrian fatality crisis. We need look no further than Hoboken to find a city that has managed four years without a pedestrian fatality. The City of Hoboken has made a concerted effort to transform its streets during standard repaving efforts into complete streets, facilitating safe crossings for pedestrians, bicyclists, and importantly, people with disabilities who use a walker or a wheelchair when traversing urban streets.

The attention to street safety and fatality rates is increasing in tandem with a greater focus on “Vehicle Miles Traveled” (VMT), a measurement that advocates assert provides more information than measurements of congestion, speeds, or greenhouse gas emissions alone. Looking closely at VMT in tandem with land use patterns can assist planners and transportation agencies in reducing car trips overall (along with congestion and fatalities), by informing decision-makers about where to build denser housing and mixed-use developments, reduce speeds, add bus-only lanes, or expand public transit options.

“New Jersey Future believes that safe street redesign and embracing vision zero principles will facilitate lower fatalities, vehicle miles traveled, and greenhouse gas emissions,” said Tim Evans, research director with New Jersey Future in a statement released in response to Smart Growth America’s Dangerous By Design report.

State Senator Diegnan and Assemblyman Karabinchak introduced a bill in June 2022, S2885/A4296, which would establish a Vision Zero Task Force to address traffic safety for all road users by prioritizing “access, equity, and mobility” and to advise state leaders and agencies on policies and programs to “help achieve the goal of zero traffic fatalities and serious injuries” on New Jersey’s streets and roadways.

“At the end of the day, this all boils down to lives on the line. We have an imperative to reduce fatalities on our streets with safe design, just as we have a duty to cut our greenhouse gas emissions by reducing car trips and vehicle miles traveled. If we want people to drive less, we need to make safe places for people to travel without a car. Fostering safer street design will encourage people to consider multi-modal and low-emission transportation options by making walking, biking, and scooter trips more inviting to New Jerseyans,” stated New Jersey Future’s executive director, Peter Kasabach.

Opportunity to Participate in a Pilot Program to Track Vehicle Miles Traveled in New Jersey

July 19th, 2022 by Kimberley Irby

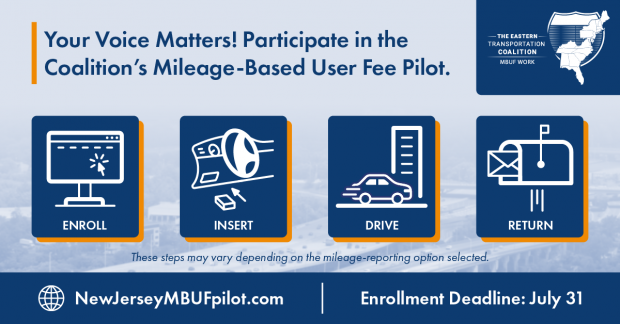

Image Credit: The Eastern Transportation Coalition

Did you know that a fuel tax you pay at the pump is largely responsible for funding a well-functioning transportation system that gets you to where you need to go, delivers packages to your door, and keeps groceries on the shelves? But as vehicles go farther on less fuel and some stop using any fuel at all, it becomes harder to maintain our aging transportation system.

The Eastern Transportation Coalition, a partnership of 17 states and Washington D.C., needs your help to explore an alternative approach, called a Mileage-Based User Fee (MBUF), which means each driver pays for the miles they drive instead of the fuel they buy.

In addition to being a viable alternative to fuel tax funding, it could also help New Jersey track where and how much driving is happening. This, in turn, could be incredibly helpful as the state promotes less car dependency in the pursuit of co-benefits such as reduced greenhouse gas emissions, and greater access and affordability.

To better understand how a Mileage-Based User Fee program could work, the Coalition is conducting a Pilot Program in New Jersey and they want you to join and tell them what you think! It is free to participate, and there are strict privacy protection measures to safeguard your data.

Here’s how to join the Pilot in four easy steps:

- Enroll – Fill out the enrollment form by clicking the link on the website.

- Insert – Plug a small device into your vehicle to record mileage.

- Drive – Then drive as you normally do.

- Return – After a few months, mail back the device.

Image Credit: The Eastern Transportation Coalition

*These steps may vary depending on the mileage-reporting option selected.

Your voice is important, so visit NewJerseyMBUFpilot.com to learn more and enroll. Participants who qualify can receive up to $100. Have questions? Contact a Pilot team member at 609-293-7800 or by email (NewJersey MBUFpilot

MBUFpilot org) .

org) .

The Risk to Our Roofs: Considering and Harnessing the Climate-Housing Nexus

July 11th, 2022 by Michael Atkins

Plenary session “The Risk to Our Roofs: Considering and Harnessing the Climate-Housing Nexus” during the New Jersey Future and APA-NJ New Jersey Planning and Redevelopment Conference 2022 at the Hyatt Regency, New Brunswick on June 16, 2022. Photo Credit: Keith Muccilli

New Jersey faces major challenges with the dual threat of climate change and housing unaffordability. While at face value, these two issues seem to pertain to natural or built environments, respectively, the two are inseparably linked and must be addressed in tandem.

At the 2022 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference, co-hosted by New Jersey Future and the American Planning Association New Jersey Chapter (APA-NJ), the intersection of housing and the environment was given center stage during the lunch plenary session. This session featured a row of experts in this field, moderated by Thomas Dallessio, Vice President of Policy, APA-NJ.

As the experts enumerated, the idea of forming “resilient cities” is aimed at providing protections for residents and erecting environmental buffers to protect the people housed in climate vulnerable communities. As opening panelist Dana Bourland, senior vice president at the JPB Foundation, outlined, “gray” communities—or the existing impermeable hardscape and car-centric design of many buildings, commercial corridors, and communities—exacerbate inequalities that overburden people of low-income and Black and Brown communities.

Dana Bourland speaking at New Jersey Planning and Redevelopment Conference 2022. Photo Credit: Keith Muccilli

“Green” developments seek to capitalize upon climate resiliency and carbon sequestration by utilizing recycled materials, alternative energy sources (i.e. solar roofing), and integrative design into the fabric of the community. Through integrative design, low-income and eldery residents can more easily live car-free or conveniently utilize multimodal transportation options that encourage public health and reduce carbon transportation emissions. Bourland is the author of “From Gray to Green: A Call to Action on the Housing and Climate Crises”, a book on this subject recommended to all audience members and readers, and has also developed a publicly available toolkit, “The Green Communities Criteria,” which is available online at greencommunitiesonline.org.

Georgeen Theodore—professor at Hillier College of Architecture and Design of the New Jersey Institute of Technology—shared a rich presentation that explored best practices in design and redevelopment to foster physical resilience from storms and flooding, focusing on housing development and environmental landscaping in coastal communities. Theodore sought to illustrate techniques to move residents from low-lying flood prone areas to higher ground, by both constructing new resilient housing and providing floodplain buy back funding for existing residents to assist their move. She also highlighted that floodplain reclamation presents an occasion to develop grassy wetland areas that can serve not only as a buffer between the bay and housing in a storm, but provide access to open space and recreational opportunities for residents through all seasons.

Georgeen Theodore speaking at New Jersey Planning and Redevelopment Conference 2022. Photo Credit: Keith Muccilli

Kelvin Broddy grounded the entire conversation with real-life, firsthand experiences by sharing his perspective of flooding and housing in Newark. Boddy is director of Healthy Homes and Communities, Housing and Community Development Network of New Jersey (HCDNNJ), a statewide membership-based organization with over 270 members including foundations, businesses, community development corporations,and private developers. Together, members work to construct affordable housing that is “healthy in both construction and location.” Affordable housing is too often constructed in undesirable and precarious land, or cordoned off into one section of a city or town. These development patterns leave residents of affordable housing–-who are low-income and/or of Black and Brown communities—vulnerable to not only floods, but extreme heat and poor air quality.

Kelvin Broddy speaking at New Jersey Planning and Redevelopment Conference 2022. Photo Credit: Keith Muccilli

In the past decade, Superstorm Sandy (2012) and Hurricane Ida (2021) expose the vulnerability of affordable housing units in Northern New Jersey, and the rate we can expect extreme weather events to continue to occur. Boddy pointed to examples in Newark, Elizabeth, and Penns Grove to illustrate the placement of affordable housing in flood-prone areas, or along tributaries that stand to flood regularly in the century ahead.

Not all hope is lost, as Boddy issued a series of solutions proven to address the issue of affordable housing vulnerability to flooding associated with climate change. Primarily, new public and affordable housing should be developed without residences on the ground floor. Existing affordable housing must be preserved, and in some cases restorated, so that cities and towns do not lose their affordable housing stock in the wake of an extreme weather event. Finally, tree plantings and green space improvements in existing and future affordable housing complexes can cool temperatures and improve air quality. Boddy concluded, “With an influx of money from both state and federal governments for the development of affordable housing, it is more important than ever that we ensure both new and old development can meet any challenges the state’s climate presents.”

The State of New Jersey’s Housing Market: We Need More

July 11th, 2022 by Tim Evans

Breakout session “The State of Housing in New Jersey” during the New Jersey Future and APA-NJ New Jersey Planning and Redevelopment Conference 2022 at the Hyatt Regency, New Brunswick on June 16, 2022. Photo Credit: Keith Muccilli

New Jersey is facing an acute housing shortage. Nationally, we are millions of housing units short of meeting demand, and the situation is proportionally worse in New Jersey. That was the big-picture message delivered by Debra Tantleff, founding principal of Tantum Real Estate, to kick off the session on The State of Housing in New Jersey at the 2022 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference, hosted jointly by New Jersey Future and the New Jersey chapter of the American Planning Association. Demand for housing in New Jersey is far exceeding supply, especially middle-income housing. Failure to produce enough housing, both in terms of the types of housing that potential residents are looking for, and in the kinds of places where today’s homebuyers and renters want to live, puts upward pressure on prices and incentivizes people to look elsewhere.

Adam Gordon, executive director of the Fair Share Housing Center, said that housing unit growth did not keep pace with population growth in the 2010s, particularly because of low production of multi-family housing in the first half of the decade. The slowdown happened in the wake of the 2011 dissolution of the Council on Affordable Housing (COAH), the state agency that had been in charge of overseeing municipal compliance with the Mount Laurel Supreme Court decisions, which require municipalities to allow the creation of housing for low- and moderate-income households. Many towns have chosen to satisfy their Mount Laurel obligations via mixed-income, multi-family projects that include a lower-income component along with market-rate units. The interim between the demise of COAH and the subsequently instituted system of enforcement by lower courts created temporary uncertainty about the determination of municipalities’ obligations, leading to a temporary dropoff in multi-family construction in general.

The lull in multi-family housing production illustrates the extent to which the state implicitly relies on Mount Laurel requirements to provide not just housing for low- and moderate-income households but much of the state’s new middle-income housing as well. Without Mount Laurel, it is not clear how much multi-family housing the state would be producing at all—and it might not be very much, if the rest of the New York metropolitan area is any indication. In the 2010s, the counties of northern New Jersey produced vastly more new housing units per capita than did Long Island, the Hudson Valley, or southwestern Connecticut. This raises questions as to whether relying on the Mount Laurel mechanism is really a sustainable long-term solution for ensuring that the middle class can continue to afford to live in New Jersey.

Fortunately, not all towns take a reactive approach to producing middle-class housing. Scotch Plains is an example of a suburban municipality proactively trying to adapt to evolving market demand for compact, walkable neighborhoods. Thomas Strowe, director of Redevelopment for the Township, spoke about the Township’s recent redevelopment efforts, which are focused on invigorating its small downtown and turning it into more of a mixed-use destination. The Township seeks to make downtown living available to a wider range of households via mixed-income projects that will be enabled by downtown overlay zones and density bonuses. The bonus requires a 20% inclusionary component (that is, 20% of the units must be affordable to low- and moderate-income households), along with public open space and other amenities, thus allowing the Township to address its Mount Laurel obligations while pursuing a broader redevelopment goal. Multiple developers are seeking to take advantage of the bonuses, another sign of the pent-up demand for in-town living.

Breakout session “The State of Housing in New Jersey” during the New Jersey Future and APA-NJ New Jersey Planning and Redevelopment Conference 2022 at the Hyatt Regency, New Brunswick on June 16, 2022. Photo Credit: Keith Muccilli

Meanwhile, on the other end of the spectrum are older, more urbanized municipalities where, until recently, the main problem was not lack of supply but lack of demand for market-rate housing. Tiffany Harris-Delaney, the Director of Policy, Planning, and Development for the City of East Orange, talked about the flurry of recent development projects happening in her city, particularly near its two NJ Transit commuter rail stations. Harris-Delaney pointed to East Orange’s diverse housing stock (84% of its housing units are something other than single-family detached) as a reason the city has long been affordable to a wide range of household incomes, and city leaders would like to keep it that way.

In the face of surging demand for walkable and transit-accessible neighborhoods, East Orange is more vulnerable to the displacement of existing residents than most places, with renters comprising 76% of its households, so together, the City and developers have worked to ensure that new projects incorporate both market-rate and lower-income units, in order to mitigate upward pressure on prices. Gordon said the Fair Share Housing Center has been working with many older urban centers facing similar pressures, encouraging them to adopt inclusionary zoning ordinances–that is, requirements that new residential developments designate a certain percentage of their units for occupancy by low- and moderate-income households–as a way of getting ahead of the displacement issue as market demand returns to cities after decades of absence.

Panelists agreed that cooperation between the public and private sectors makes housing production easier, especially for inclusionary projects. Debra Urban, chief of Multifamily Programs at the New Jersey Housing and Mortgage Finance Agency and the session’s moderator, said that her agency has multiple programs that are designed to help close financing gaps for inclusionary projects, as well as the well-known Low Income Housing Tax Credit program, which has been responsible for facilitating affordable housing projects in a wide variety of places in New Jersey. Tantleff mentioned the importance of payments in lieu of taxes (PILOTs) and redevelopment area bonds (RABs)—both of which require municipal participation—for making projects cheaper and simpler to finance. She also advised towns to talk to developers in advance about the feasibility of different kinds of housing in redevelopment plans. Strowe pointed out that Scotch Plains has adopted a redevelopment plan for its publicly-owned properties and is soliciting proposals. Tantleff and Gordon each praised both Scotch Plains and East Orange for thinking ahead about the kinds of development they want to see and working with developers to make it happen.

When asked whether the goals of affordable housing advocates and the goals of private developers will continue to coincide over the next 20 years, Tantleff said essentially yes. As Gordon explained, there is so much pent-up demand for housing that it will take a long time for supply to catch up, part of the reason that developers are still able to build for the top of the market in most places. If New Jersey wants to be able to continue to welcome or retain people of all income levels, it needs to both produce more multi-family housing at scale, and preserve existing affordable housing supply. This may involve considering statewide zoning reform, in addition to relying on the Mount Laurel system to incentivize the production of middle-income housing options, and it may mean that inclusionary zoning ordinances should become the rule rather than the exception, in order to avoid displacing existing residents. One way or another, New Jersey needs to find a way to break its housing supply logjam. As Gordon put it, “We shouldn’t need subsidies to produce a $500,000 house.”

State Agencies Shape Infrastructure Programs to Address 21st Century Challenges

July 11th, 2022 by Chris Sturm

Plenary session, “Addressing Key Redevelopment Challenges and How New Federal Funding Will Help Us Get There” during the New Jersey Future and APA-NJ New Jersey Planning and Redevelopment Conference 2022 at the Hyatt Regency, New Brunswick on June 16, 2022. Photo Credit: Keith Muccilli

Communities Advised to Prepare Now to Access Funds

With a record state surplus and billions of dollars of federal funding from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), New Jersey communities enjoy a rare opportunity to address redevelopment challenges, explained Peter Kasabach, New Jersey Future’s executive director. But a “lack of readiness” will be their biggest obstacle to accessing those funds, asserted New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) Commissioner Shawn LaTourette. He and co-panelists Preethy Thangaraj, policy advisor to Governor Murphy, and Tim Sullivan, CEO of the state’s Economic Development Authority, each described their various approaches to harnessing the new federal funds at the 2022 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference plenary session, Addressing Key Redevelopment Challenges and How New Federal Funding Will Help Us Get There.

Local officials can look to the Governor’s Office for information and guidance on new federally-funded programs, according to Preethy Thangaraj. A soon-to-be-launched website will act as a central source for IIJA opportunities, including $2.5 billion in discretionary grant opportunities for transportation, water, broadband and green and complete street projects. Newly appointed Infrastructure Coordinator Richard Sun is connecting locals with state agency staff who can help them apply for funds.

Tim Sullivan noted that the bulk of IIJA funding for New Jersey will come to the state through the federal Surface Transportation Reauthorization Act. The remainder is dedicated to water, energy, and broadband infrastructure, with some monies for workforce development. Together with the state’s share of funding from the federal American Rescue Plan, Sullivan argued that these monies could enable the state to completely finish work on certain issues such as lead in drinking water, so “kids don’t need to drink that water ever again.”

Plenary session, “Addressing Key Redevelopment Challenges and How New Federal Funding Will Help Us Get There” during the New Jersey Future and APA-NJ New Jersey Planning and Redevelopment Conference 2022 at the Hyatt Regency, New Brunswick on June 16, 2022. Photo Credit: Keith Muccilli

Can IIJA funds help the government focus on the future and prepare for rising sea levels and more extreme precipitation? Commissioner LaTourette explained that the NJDEP will use the new funding to change the “mechanics” of modernizing infrastructure by coordinating it with forthcoming interagency climate action plans, updated flood rules, and new spending programs. NJDEP’s share of IIJA funds will go to two areas: long-term flood protection projects for “worst-case scenarios” and local water infrastructure projects that address day-to-day concerns. The agency will funnel $1 billion for water infrastructure projects through the state’s Water Bank as it simultaneously pushes to right-size the state’s share of national water infrastructure funding.

Latourette acknowledged that the Water Bank program “shuts out” some of the communities that are the most in need, so his agency plans to engage engineers and grassroots leaders to help them successfully apply for funding. The department has also formed a Community Investment and Economic Revitalization Program to make opportunities for state-local partnership opportunities clear and available, which includes the agency’s Community Collaborative Initiative program. He added that in the next few weeks the NJDEP would announce grant programs for towns to pursue the creation of stormwater utilities.

Tim Sullivan highlighted three new EDA funding programs that seek to encourage resilient, compact growth and redevelopment:

- Aspire, a gap financing tool for real estate development projects.

- The Historic Property Reinvestment Program, a $50 million competitive tax credit program

- The Brownfields Impact Fund

EDA will receive some IIJA funding for brownfields grants and port infrastructure for off-shore wind in South Jersey. In addition, the governor’s proposed budget provides $25 million for transit-oriented development, $300 million for affordable housing, and funding to integrate climate resilience into the State Development and Redevelopment Plan.

When asked how the state will employ IIJA funds to support historically overburdened communities, Preethy Thangaraj explained that investments will center on policy imperatives in the state’s Environmental Justice Law. For example, the NJDEP map of overburdened communities will be used as a tool to prioritize investments, and the Governor’s Office will rate projects using an equity and sustainability index.

Deploying federal infrastructure dollars in New Jersey will be a team effort between proactive local governments and well-organized state agencies. Communities should prepare now by hiring grant writers to apply for funding and then planners, engineers and architects to design projects and manage construction. The benefit: infrastructure and redevelopment that is ready for growing challenges like climate change.

Social Determinants of Health: National and Local Perspectives

July 11th, 2022 by Jyoti Venketraman

Social determinants of health are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age that shape their health and well-being. In other words, these are the non-medical factors that impact health outcomes. Social determinants of health include traditional planning domains such as transportation, housing, green spaces, and social domains like good schools and access to good jobs.

Social determinants of health are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age that shape their health and well-being. In other words, these are the non-medical factors that impact health outcomes. Social determinants of health include traditional planning domains such as transportation, housing, green spaces, and social domains like good schools and access to good jobs.

At the 2022 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference, co-hosted by New Jersey Future and the New Jersey Chapter of the American Planning Association, a session titled “Social Determinants of Health: National and Local Perspectives” examined and addressed racial and health inequities through planning, policy, community organizing, and culture change by showcasing national and local perspectives. Speakers included Vanessa Barrios, the manager of Advocacy Programs at Regional Plan Association; Michael Kolber, senior planner for the City of Trenton; and Melanie Hughes McDermott, senior researcher with Sustainable Jersey at the Sustainability Institute at The College of New Jersey. The session was moderated by Pamela Russo, senior program officer at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

“Social determinants of health provide an opportunity for planners to have an expanded scope when it comes to redevelopment. In order to achieve sustainability one must incorporate equity.” said Pamela Russo, setting the stage for the session, and inviting viewers into this vital conversation.

Panelist Vanessa Barrios showcased the national perspective on how the Regional Plan Association (RPA) has integrated this lens of social determinants of health. In her presentation and comments, Barrios explained, “Health is integral to well-being. Racial justice, health equity are very vital to regional planning.” Barrios went on to stress how planners make vital decisions that shape the built environment, which in turn impacts the health and wellbeing of all communities. Using the example of RPA’s Healthy Regions Planning Association, Barrios showcased work happening nationally in 10 regions. The regions are exploring how race and racism impacts the built environment through planning, and seek to center community voices in their design process of planning. One takeaway Barrios shared was how by intentionally centering the voices of impacted communities, health equity can be integrated into regional planning to improve health outcomes.

Panelist Melanie Hughes shared a state-level perspective, highlighting Sustainable Jersey’s Gold Star in Health standard, a voluntary program for NJ municipalities. To obtain a Gold Star in Health certification, towns must use existing data, engage multi-sector stakeholders, and connect the dots between social determinants of health and potential action solutions, like access to green spaces and safe streets. Hughes shared that through their work with the Gold Star program, intersection of health and housing, Sustainable Jersey includes housing as an action area, developing a suite of actions that promote healthy housing, with a particular focus on lead poisoning.

Panelist Michael Kolber highlighted the local perspective of the City of Trenton, which was the first city in 2021 to have a Community Health and Wellness plan as part of its master plan. Kolber explained, “Everything in Trenton revolves around our master plan—housing and land use, public safety, arts and culture, [and] health.” Trenton’s Community Health Plan includes many goals, such as increasing access to food, increasing physical activity, improving access to health care, and focusing on seniors, to name a few. Trenton’s planning and zoning meetings use this health plan as part of land use applications review to determine whether the plan relates or justifies development. Decisions like removing grocery store barriers, permitting primary care facilities in all land zones, exploring equitable distribution of parks, and addressing barriers to parks that some face were shared as examples of how community health plans enable integration of health equity in planning decisions at the local level.

The panel and the discussion brought up common themes that were shared across the examples highlighted, including the vital role of cross-sector partnerships, building cross-sector consultative grassroots work, intentionally centering the voices of impacted communities in planning, and learning from past mistakes to rebuild trust. As billions of dollars for infrastructure investment begin flowing into communities across the nation, healthier and more equitable communities can be achieved when racial and health inequities are addressed through planning, policy, community organizing, and cultural change.

Warehouse Development: Regional Significance Calls for Regional Perspective

July 11th, 2022 by Tim Evans

Industries devoted to the movement and storage of goods are a pillar of New Jersey’s economy, providing jobs to nearly one out of every eight employed New Jersey residents. Growth in e-commerce and in the volume of international trade arriving at the country’s second-busiest port, the major facilities of which are located in North Jersey, are creating unprecedented demand for warehouse space. At the 2022 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference—hosted jointly by New Jersey Future and the New Jersey chapter of the American Planning Association—a session titled Warehouse Development: Regional Significance Calls for Regional Perspective drew attention to the importance of the industry, and offered advice to towns scrambling to figure out how to deal with warehouse development proposals.

Industries devoted to the movement and storage of goods are a pillar of New Jersey’s economy, providing jobs to nearly one out of every eight employed New Jersey residents. Growth in e-commerce and in the volume of international trade arriving at the country’s second-busiest port, the major facilities of which are located in North Jersey, are creating unprecedented demand for warehouse space. At the 2022 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference—hosted jointly by New Jersey Future and the New Jersey chapter of the American Planning Association—a session titled Warehouse Development: Regional Significance Calls for Regional Perspective drew attention to the importance of the industry, and offered advice to towns scrambling to figure out how to deal with warehouse development proposals.

Jim Gilbert, a member of New Jersey Future’s Board of Trustees and a former chair of the State Planning Commission, served as the session’s moderator and started off the discussion by noting that the surge in demand for warehouse space is creating a host of problems that have caught state and local leaders off guard: unanticipated demands on transportation facilities, loss of farmland, and disruptions to urban areas, among other concerns that land-use decision-makers are confronting.

The big news to come out of the session is that the Office of Planning Advocacy (OPA), which serves as the staff for the State Planning Commission, has issued guidance (viewable on their website under the heading “Reference Materials”) that is designed to help local leaders better understand the goods movement industry so they can make more informed decisions about where to site warehousing facilities. Donna Rendeiro, the executive director of OPA, provided an overview of the guidance and discussed how OPA can assist local decision makers with updating their planning and zoning to incorporate and reflect the information provided in the guidance.

Not all warehouse proposals have the same set of land-use and transportation needs or are appropriate for the same kinds of sites, a fact not well understood by local officials or residents who oppose warehouse development. To shed some light on how the industry works, Anne Strauss-Wieder, director of freight planning at the North Jersey Transportation Planning Authority, elaborated on the different types of warehouse buildings. Warehouses can range from the behemoths that receive goods coming off giant cargo ships and distribute them to smaller warehouses across the eastern half of the country to the local delivery centers from which the ubiquitous UPS or Amazon vans are dispatched to deposit packages at their final destinations, effectively performing the same role as local shopping centers but without the inbound car traffic.

Strauss-Wieder also touched on the types of vehicles that the different types of facilities tend to attract, an important consideration as to where a given facility might best be located relative to the transportation network. The OPA guidance has a section devoted to the hierarchy of buildings involved in goods movement and storage.

The larger facilities that are involved in wide-scale distribution of entire shiploads of goods tend to want to locate as close to the port as possible. But the older urban centers that surround the major port facilities in Elizabeth, Newark, and Bayonne are often also home to “overburdened communities,” neighborhoods characterized by high percentages of people of color or lower-income households. Because many of these neighborhoods have historically experienced a variety of environmental stressors, the legacy of New Jersey’s industrial past, the pollution emitted by the steady stream of trucks accessing the warehouses can represent a much more significant cumulative impact here than elsewhere. The OPA guidance has a section on air quality and health impact considerations, to draw attention to these cumulative impacts and recommend against locating certain kinds of goods-movement facilities in these neighborhoods.

This is not to say that warehouse development cannot offer positive outcomes to urban communities, however. Wilda Diaz, former mayor of Perth Amboy, described how a warehouse proposal provided her city with the opportunity to clean up a contaminated site formerly occupied by an abandoned steel mill. As part of a comprehensive agreement with the City that included numerous improvements (e.g. roads, stormwater infrastructure, implementation of green and sustainable initiatives), the warehouse developer mitigated the environmental hazards on the property, turning a polluted eyesore into a new source of tax revenue for the city and a source of employment for nearby residents–an important benefit for the municipality with the highest unemployment rate in Middlesex County. What’s more, the developer’s improved connections to the local street network enable some local residents to walk to work—especially important in a place where many households can’t afford cars—while allowing trucks to access the regional highway network in the other direction without having to travel on local streets. Diaz explained that communicating the potential benefits of the project via a public outreach campaign was important in overcoming negative perceptions, and that negotiating the benefits agreement with the developer was key to getting buy-in from the surrounding community.

Warehouses pose a different set of problems in more outlying locations. Julia Somers, executive director of the New Jersey Highlands Coalition, mentioned the risk of paving over important groundwater recharge areas in the Highlands, which are traversed by Interstates 78 and 80, two of the major arteries feeding into the port areas in North Jersey. The stretches of Warren and Hunterdon counties along I-78 are also home to some of the state’s prime farmlands, which can also be attractive to warehouse development because of proximity to the highways and lower land prices than at closer-in locations. New Jersey is a leading nationwide producer of certain fruit and vegetable crops, so when agriculture and warehousing compete for the same land parcels, it sets up a conflict between two industries of statewide importance, a conflict that may not be optimally resolved by leaving the decision to the local unit of government.

Warren County commissioner Jim Kern, as both a former mayor and now a county official, spoke to the need for regional coordination. He talked about New Jersey’s “home rule” system that invests municipal governments with power over land-use decisions and how the promise of property-tax revenue often leads towns to court development that may have negative effects on the environment or local quality of life, both within the host municipality and in surrounding jurisdictions. Somers pointed out that in other cases municipalities zone land for industrial use as a sort of placeholder, mainly to prevent it from being developed as housing, and are unprepared when a commercial developer proposes to actually build a warehouse on it, an example of the “be careful what you wish for” phenomenon.

As an example of what higher levels of government can bring to the table, Kern cited a Light Industrial Site Assessment that Warren County completed in 2020 that provided an overview of sites in the county that were zoned for warehousing and illustrated how many such sites were located next to roads that were not up to the task of accommodating truck traffic. In urban areas, concerns focus on trucks passing through residential neighborhoods while in rural areas the issue is two-lane roads that were not built to handle big trucks, but both situations illustrate the need to consider transportation networks when siting warehouses, which local governments may not be best equipped to do. The OPA guidance has a section intended to educate local officials about this issue.

In general, the OPA guidance is designed to offer a statewide perspective on warehousing, covering a broad set of issues. In the coming months, New Jersey Future will be reviewing the guidance and looking for ways that it can be institutionalized in state agency policies and practices, and we will be exploring the potential of its proposal for county-level technical advisory committees as a vehicle for bringing together the perspectives of multiple stakeholders as inputs into the warehouse siting process. We applaud the OPA guidance as a critical step toward a more systematic approach to accommodating growth in one of the state’s key industries.

Walking the Talk: Planning for Places that Actualize Equity and Inclusion

July 8th, 2022 by Kimberley Irby

“In this era of racial reckoning, especially triggered by the murder of George Floyd, we have to pause and ask what our role is as a profession, what responsibility we have had in creating the societies in which we live, and how we rectify [problems] with an equity lens,” stated Eleanor Sharpe, deputy director for planning and zoning in the City of Philadelphia, a panelist in the first plenary session of the 2022 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference, hosted by New Jersey Future and and the New Jersey chapter of the American Planning Association.

“In this era of racial reckoning, especially triggered by the murder of George Floyd, we have to pause and ask what our role is as a profession, what responsibility we have had in creating the societies in which we live, and how we rectify [problems] with an equity lens,” stated Eleanor Sharpe, deputy director for planning and zoning in the City of Philadelphia, a panelist in the first plenary session of the 2022 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference, hosted by New Jersey Future and and the New Jersey chapter of the American Planning Association.

The virtual plenary, titled Walking the Talk: Planning for Places that Actualize Equity and Inclusion, served as a follow-up to the previous year’s plenary called the Geography of Equity and Inclusion, which covered a big picture view of spatial segregation in the nation and in New Jersey specifically, as well as how we could mitigate it. The goal for this year’s plenary was to clarify what the planning and redevelopment community can and should do to achieve equity and inclusion in our communities.

The panel, moderated by Zunilda Rodriguez, senior associate at Nishuane Group, featured four distinguished speakers, including Sharpe; Maritza E. Mercado Pechin, deputy director of the Office of Equitable Development in the City of Richmond, VA; April de Simone, principal at Trahan Architects and co-founder of designing the WE; and Allison Ladd, deputy mayor and director of the Department of Economic and Housing Development in the City of Newark. During this plenary, speakers emphasized the importance of building trust with historically marginalized communities and establishing a robust process for their involvement throughout the stages of development or redevelopment, from planning to implementation.

How can we support accountability and transparency at the local level?

In response to this first question posed by Rodriugez, Mercado Pechin offered an example from the City of Richmond, citing a transportation policy guide that shared the blunt history of inequitable transportation projects, and thus, set the stage for choosing projects that could help remedy past mistakes. Later on, Pechin highlighted the legitimate concern of displacement from a project that will reconnect a community previously severed by a highway, and said that her office is examining solutions, such as ensuring there are more homeownership opportunities.

De Simone, a New York-based architect who co-led a national exhibit project called Undesign the Redline, reinforced the point that understanding historical context is necessary to avoid perpetuating inequitable outcomes, especially through projects that aim to undo the mistakes of the past, like highway capping. She reminded us not to assume that “just because we see development happening [in historically marginalized communities]… that the systemic conditions of inequity and disparities of poverty, health, and wealth-building opportunities are solved.”

How can we begin to rebuild trust with communities that have been left behind with empty promises for decades?

Several speakers brought up the challenges of building trust with the community and the audience asked for suggestions to tackle them. Sharpe, with the City of Philadelphia, urged planners to “listen more and talk less” when engaging with the public, noting that just hearing and acknowledging people is half of the work. Beyond this, Ladd, with the City of Newark, underscored the ability to adapt based on what the community is saying, as well as the need to be consistent with execution (i.e., following through on what one says they’re going to do). Ladd also acknowledged that “sometimes the listening and hearing parts are challenging, but we have to hear it even when it’s aggressive or uncomfortable, because that friction is actually where change happens.”

How can we thread equity and inclusion into local planning and/or processes?

Throughout the discussion, panelists echoed Sharpe’s saying, “slower is faster,” emphasizing that good community engagement requires time and deliberate, intentional focus. Sharpe also illustrated that effective engagement can empower communities to have a meaningful role in the creation of projects that will affect them. For example, she referred to the creation of Philadelphia’s Citizens Planning Institute, which educates cohorts of residents on planning and zoning, enabling them to translate technical aspects of government projects to their neighbors and assuage their concerns.

Additionally, Mercado Pechin shared that the City of Richmond used a similar community ambassador mechanism during their master plan process. All panelists agreed on the importance of compensating community volunteers for their time, both to ensure a socioeconomically diverse group and to affirm that insights from their lived experiences are just as valuable as the work they pay consultants to do.

To ensure equity and inclusion in community redevelopment, the panelists suggested that we intentionally engage in a way that brings different people to the table, especially those who have been historically left out. Though this can be challenging when trust is lacking, it is critical to build, or rebuild, a mutually beneficial relationship. Sharpe continually emphasized we are all learning and that there is no easy answer or silver bullet. Nevertheless, Sharpe reminded us that, “These are exciting times. There is a lot of opportunity as the world is shifting and changing, and our profession can show up and make our mark.”