New Jersey Future Blog

Helping NJ Drive Less: The Need to Dedicate Funding to Transit and Safe Streets

January 31st, 2023 by Kimberley Irby

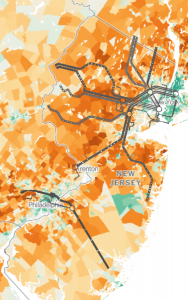

The New York Times (NYT) Climate Impact Map of New Jersey overlaid as closely as possible with NJ Transit lines, emphasizing the NYT data which shows how people living in denser areas, where there is typically less driving, are responsible for fewer carbon emissions.

Electric vehicles are great, but they won’t reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the transportation sector fast enough, nor will they do anything to alleviate congestion. This past October, the United Nations published the Emissions Gap Report 2022, declaring that an important action for the transportation sector is to “integrate land use and transportation planning to prioritize public transit over private automobiles.” As we confront climate change alongside congestion, road fatalities, and high gas prices, it is imperative that New Jersey not only facilitates increasing electric vehicle adoption, but focuses on the range of solutions that encourage people to drive less.

Though record-high gas prices last year reminded us of the expense of vehicle ownership, the costs of car dependency are more than economic. Traffic deaths are on the rise, revealing the human cost of our dangerous streets and roads. People waste precious hours of their lives idling in traffic, which emits pollution that disproportionately harms low-income and Black and Brown communities too often encroached upon or divided by urban highways. Meanwhile, there are many benefits of transit, biking, and walking, including improvements in affordability and equity, health and safety, climate and economy, and increasing leisure time.

State and federal transit agencies, nonprofits, and private partners are aiming to reduce our dependence on private vehicles, but there is much more to be done. Alternatives to driving mostly include active transportation (e.g., walking, biking, rolling) and public transit (e.g., bus, rail, light rail). We must ensure more money and planning goes towards those activities. This would mean sufficient capital and operating funds to ensure public transit is efficient and reliable and active transportation routes are safe and accessible.

We can also address the issue of car-dependency through the lens of land use: building destinations closer together, ensuring safe connectivity between transit stations, and creating safe streets. What is known as “Complete Streets” design and implementation is crucial to improve safety and accessibility for all active transportation modes. Overall, there is a need to be more intentional about creating places and investing in infrastructure that support both driving shorter distances and using other modes of getting around.

NJ Transit, in particular, is a vital service and tool in helping New Jerseyans drive less. It is the nation’s largest statewide public transportation system of buses, rail, and light rail, and it serves nearly one million riders per day. Despite its potential to get people out of cars, there is currently no reliable, dedicated source of funding for the system’s essential operating needs. For years, NJ Transit has relied on rider fares and funding diverted from various sources, such as the state’s Clean Energy Fund, to sustain itself. Since the onset of the pandemic, NJ Transit has utilized federal relief to plug budget gaps, but the agency faces a fiscal cliff when aid money runs out in 2026. With the push for more electric vehicles on the road, gas tax revenue is expected to shrink, reinforcing the imperative to find a steady source of funding elsewhere.

NJ Transit requires capital funds to maintain a state of good repair, upgrade the existing system, and become more environmentally sustainable, by, for example, acquiring electric buses. Operating funds are just as vital, allowing the agency to provide reliable, affordable service. The first draft of next year’s state budget will be issued in February, and now more than ever, we need our legislators to commit to adequate funding for NJ Transit operations, both in the short- and long-term, that does not detract from the agency’s capital budget or the state’s Clean Energy Fund. Strengthening NJ Transit helps all New Jerseyans when it comes to transportation: it directly supports those who do not want to rely on or are not able to afford private vehicles, and indirectly supports drivers by reducing congestion.

We all benefit from living and working in places where we have the flexibility to move between critical places without relying on a car, and we should demand relevant solutions from our elected leaders. Whether you walk, bike, ride public transit, or simply want reduced congestion, prioritizing funding for strategies that can ultimately help reduce car dependency improves all of our commutes and air quality. As we strive to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions, especially from transportation, and to be a state that is rich with various mobility options, we must prioritize center-based design, implement safe street design, and provide operating funds for public transit. Doing so will not only help us mitigate the climate crisis, but also will enable better placemaking to improve the lives of all New Jerseyans.

Transit-Oriented Development is Pedestrian-Oriented Development

January 30th, 2023 by Tim Evans

Trenton Transit Center, Trenton NJ. Photo Credit: New Jersey Future

Despite being the most densely populated state in the country with over 150 train station towns, New Jersey is not a safe place for pedestrians of any age. In our effort to reduce car dependency, increase pedestrian safety, and encourage placemaking that serves the public, NJ ended 2022 with several announcements designating funds for advancing pedestrian and bicycle safety and transit-oriented development (TOD), indicating that the administration recognizes the importance of creating and fostering transportation options besides driving. Here’s a few recent developments of note:

- NJ Transit receives federal grant funding to study light rail in Hudson and Bergen Counties. [NJ.com]

- New engineering contract indicates major step forward for light rail line connecting Camden and Glassboro. [NJ.com]

- Murphy Administration disperses money across 56 municipalities to implement street safety and connectivity projects. [ROI-NJ]

The common goal among these projects is compact, walkable urbanism. Transit-oriented development must be pedestrian-oriented development, since transit riders become pedestrians the moment they step off the bus or train. Before private automobiles became the default method of transportation, most towns, including most of New Jersey’s urban centers and first-generation “streetcar” suburbs, were designed with walking in mind. The whole point of transit-oriented development was to enable transit riders to safely access the station on foot, and to access other commercial destinations along the way. These same clusters of destinations also made trips shorter and more efficient, often without needing a car, for other local residents who were not transit commuters.

These older centers present a massive opportunity for NJ to reduce car dependency. Centers with multiple destinations (sometimes including a transit station, sometimes not) located within easy walking distance fell out of favor in the second half of the 20th century, as automobile ownership became nearly universal and development patterns changed to focus on accommodating cars rather than people. But the legacy of walkable urbanism is still visible in New Jersey’s relatively low rate of vehicle ownership, compared to other states that experienced most of their development after the car became dominant. In NJ, 11.2% of all households1 do not own a vehicle, the third-highest rate in the country after New York and Massachusetts. (This translates to about a million people who are reliant on some other mode of transportation besides a car for their daily needs.) And another 34.8% of households have only one vehicle available, bringing the share of NJ households that are able to live either car-free or “car-light” (only one vehicle) to 46%, or almost half.

The good news is that towns that embody the live-work-play-shop environment are becoming popular again, giving states like New Jersey with many older centers a competitive advantage. The 153 municipalities in New Jersey that host a transit station (rail, ferry, or major bus terminal) accounted for 68.6% – more than two-thirds – of total statewide population growth between 2010 and 2020, up substantially from only 27.8% of total growth in the 2000s and 35.8% in the 1990s. More precisely, the 124 municipalities that best embody the concept of walkable urbanism (with or without transit stations) and score high on all three New Jersey Future smart growth metrics—high activity densities (people + jobs per square mile), mixed-use downtowns, and well-connected, walkable street grids—together accounted for more than half (57.5%) of the statewide population increase in the 2010s, compared to only 13.6% of total growth in the 2000s.

Compact, walkable, mixed-use centers produce a host of societal benefits. For one thing, given the transportation sector’s outsized role in the state’s overall carbon footprint, enabling people to take at least some of their trips on public transit, or by non-motorized means —and shortening travel distances for those trips that are still taken by car—is an effective strategy to reduce the state’s greenhouse gas emissions without waiting for electric vehicles. Reducing the need to drive by making non-driving options more accessible and comfortable would also address other problems that electrifying the vehicle fleet will do nothing to resolve, such as reducing traffic congestion, improving pedestrian and bicyclist safety, reducing the expenses involved in owning a vehicle (especially important for lower-income households), allowing people to spend less time in the car commuting and running errands, improving public health as a result of more people using more active modes of transportation, and reducing per-capita infrastructure needs and the public expenditures they engender.

To encourage less car dependency, alternatives must be safer, more enjoyable, and available to more people. To this end, transportation planners at the New Jersey Department of Transportation, New Jersey Transit, and at the county and municipal level need to include the needs of non-drivers as an integral part of the planning process and not just as an afterthought. This includes incorporating pedestrian improvements into efforts to promote TOD. Because all users of the transportation system are pedestrians at some point.

__________________

12021 American Community Survey one-year estimates

New NJDEP Watershed Improvement Plan Requirement and What This Means for Municipalities

January 4th, 2023 by New Jersey Future staff

By Lindsey Sigmund and Patricia Dunkak

Stormwater picks up oil, trash and other contaminants. If it is left untreated, the stormwater conveys the contaminants into streams. Photo credit: Andrew Tabas. Location: Bordentown, NJ

In our highly developed state, upgrading and retrofitting New Jersey’s stormwater infrastructure and reducing impervious cover is a key way to address nonpoint source pollution. It is estimated that up to 60% of the State’s existing water pollution is attributable to stormwater and nonpoint sources of pollution. Stormwater best management practices (BMPs), including green infrastructure, are an integral part of improving the quality of New Jersey’s lakes, rivers, streams, and bays, and reducing dangerous flooding events worsened by climate change.

Pipes convey stormwater from impervious surfaces into the Delaware River. Photo credit: Andrew Tabas. Location: Trenton, NJ.

New Jersey’s Department of Environmental Protection’s (NJDEP) newly issued MS4 permit reflects a move toward watershed level planning for addressing water quality issues and flooding in New Jersey’s communities. The 2023 Tier A Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System (MS4) permit went into effect on January 1, 2023, and the implementation of its requirements on the local level will help address water quality and stormwater issues related to new and existing development. New Jersey already has a high number of impaired water bodies and experiences frequent flooding. The problem is anticipated to get worse: according to the New Jersey Scientific Report on Climate Change published in 2020, “surface and groundwater quality will be impaired as increased nutrients and contaminants enter waters due to runoff from more intense rain events.” The new MS4 permit is an opportunity to improve local implementation that will protect New Jersey’s waterways in the face of climate change.

What is an MS4 permit? The state issued permit requires municipalities with separated stormwater systems—essentially any municipally owned stormwater infrastructure that is not a combined sewer system (CSS)—to address their Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs). The TMDL program identifies impaired streams and the pollutants contributing to their degradation. Despite prior MS4 permits and their requirements for municipalities to address water quality impairments, an overwhelming number of municipalities have not achieved compliance, and many of New Jersey’s waterways are still considered impaired.

What this new permit means for municipalities. A significant shift from 2018, when the last permit went into effect, is the change in the number of municipalities that are now considered Tier A. All towns previously considered Tier B, over 100 municipalities, have been reclassified as Tier A. This reclassification means all of New Jersey’s municipalities are subject to permitting obligations informed by federal regulations, which include more stringent requirements set forth in the Clean Water Act. Another significant change from 2018 is the inclusion of a Watershed Improvement Plan (WIP) requirement. The WIP process and its eventual implementation will begin to address nonpoint source pollution throughout New Jersey. This process includes three phases for communities to map out actions to improve water quality by reducing pollutants and reducing or eliminating flooding in municipalities. The three steps to the WIP process over the five year permit cycle include:

- Mapping: Municipalities are required to map all publicly and privately owned stormwater infrastructure, impervious cover, and other relevant data by 2026.

- Planning: Communities will outline potential water quality improvement projects, provide an estimate of funding necessary for these improvements, and provide other relevant water quality data by 2027.

- Final Plan and Implementation: Municipalities will submit final project locations for water quality improvement projects by 2028.

Despite progressive state requirements, there will be compliance obstacles. Resources are currently available for municipalities to get started, but more guidance and technical assistance is needed to ensure compliance, especially for reclassified Tier B permittees. New Jersey Future and partners will update and provide resources for MS4 permittees made available through the New Jersey Green Infrastructure Municipal Toolkit. Another obstacle is funding. NJDEP has identified stormwater utilities as one of the potential funding mechanisms for WIPs and other MS4 permit obligations. Stormwater utility fees, based on how much hard surface, such as rooftops or pavement, is on a property, provide a dedicated source of funding for upgrading and maintaining stormwater infrastructure, including green infrastructure. However, state agencies could and should provide additional funding through grants to supplement financing provided through the state Water Bank to ensure compliance.

Bioswale in a parking lot in Asbury Park, NJ. Image Credit: New Jersey Future

Stormwater pays no mind to municipal or political boundaries. This new state mandated watershed planning approach to addressing water quality and flooding is a step in the right direction. However, watersheds, much like flood waters, do not follow municipal boundaries. Therefore municipalities should be working together to share resources and plan on a regional level to effectively address stormwater issues in their watersheds. If properly implemented, this new permit will improve water quality and reduce flooding, which is more important than ever as New Jersey braces for and seeks to minimize the impacts of climate change.

NJDEP Finalizes Water Infrastructure Investment Priorities for 2023

November 29th, 2022 by New Jersey Future staff

Photo Credit: Moriah Kinberg

By Brianne Callahan and Lindsey Sigmund

All New Jerseyans deserve to drink clean water, to avoid flooding and sewage backups in their homes and neighborhoods, and to pay affordable water and sewer charges. Every single one. Unfortunately, we’re not there yet. Today, our state’s outdated, overwhelmed, and undersized water systems are failing at an alarming rate, endangering public health and public safety, and holding us back from being the healthy, vibrant, and resilient state that we want to be. Staggeringly, an estimated $26 billion is needed to fix New Jersey’s water infrastructure over the next 20 years.

The good news is that we’re getting closer. To begin addressing our infrastructure funding gap, our Governor and Legislature allocated $300 million of New Jersey’s American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) dollars in June, 2022. Following our state leadership’s example, the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) announced that $248 million of this ARPA funding will be used to address combined sewage overflows (CSOs), in which localized flooding and raw sewage is dumped into rivers and streams from older water systems. This is welcome funding for New Jersey’s 21 CSO communities, and we are excited about what this funding will accomplish. It certainly seems like a lot of money, but it’s only a small fraction of the billions needed to improve our water infrastructure.

Let us explain. Throughout New Jersey, there are a myriad of infrastructure needs. Our systems have been sorely neglected over the last 50 years, and, in addition to addressing CSOs, communities are required to replace lead service lines by 2031 and comply with ever increasing stormwater management requirements—a necessary, but often prohibitively costly step towards building more resilient water systems in communities. The NJDEP Intended Use Plan for federal and state water infrastructure funding includes 679 water infrastructure projects in need of approximately $6 billion in funding. The $300 million in ARPA funding mentioned above is expected to be paired with the $1 billion for water infrastructure received from the federal Bipartisan Infrastructure Law over the next five years. If you do the math, this equates to an estimated $4.7 billion gap in funding for the backlog of projects outlined in the Intended Use Plan. Further piling on, this number does not include high priority projects not yet identified and/or submitted by localities due to timing or lack of planning resources. This funding gap demonstrates in no uncertain terms the priority which water infrastructure improvements must be given in the coming years and decades, in order to protect our communities and avert even greater crises in the future.

So, let’s keep our foot on the proverbial gas. Continuing their problem-solving leadership, the Governor and the Legislature should allocate a significant portion of the estimated $1.4 billion in remaining ARPA dollars to address this funding gap and ensure ratepayer relief for New Jerseyans who would otherwise see increases in water bills, sewer bills, and possibly local property taxes. Every New Jerseyan deserves access to clean and healthy water systems, and it is the responsibility of our elected leaders to ensure this is the case.

PFAS in the Garden State: What It Is and What We’re Doing About It

November 11th, 2022 by New Jersey Future staff

By Hannah Reynolds and Brianne Callahan

If the increased prevalence of the term “perfluoroalkyl” has you scratching your head, you’re not alone! Read on to learn about per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), why you should care, and what we’re doing about it here in New Jersey.

Perfluoro- what?!

In addition to being incredibly difficult to pronounce, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a large class of human-made chemicals that repel water and oil and are resistant to heat and chemical reactions. Two of the most prevalent PFAS compounds are perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS). They are commonly used in commercial and manufacturing applications, and unfortunately they are becoming more and more infamous as they are linked to serious health effects for humans and animals.

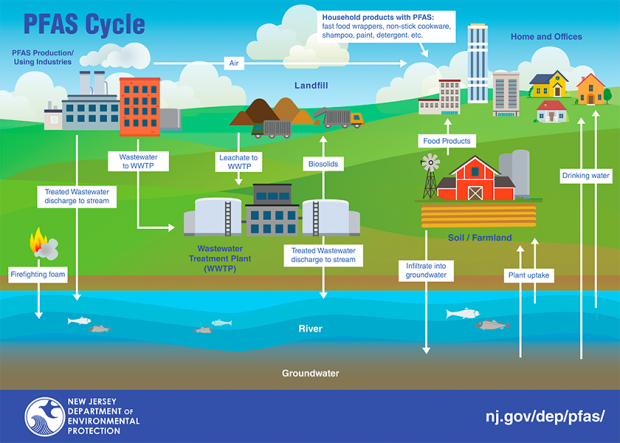

Manufacturing of PFAS chemicals began in the 1940s, to create non-stick cookware, firefighting foam, and many other common products including detergents, fast-food wrappers, paints, and even beauty products. Most famously, PFAS chemicals are present in DuPont’s teflon cookware—a fact your grandparents could most assuredly corroborate.

Why You Should Care

There’s no sugarcoating it—PFAS pose a big problem. These chemicals are linked to serious health issues for humans and animals alike, and they are wreaking havoc on communities across the United States. Known as “forever chemicals,”contaminants in the PFAS family accumulate in the body over extended periods of time, and are associated with a higher risk of health problems including liver damage, thyroid disease, decreased fertility, high cholesterol, obesity, hormone suppression, and cancer. PFAS can pass into our bodies through water, food, and air, and their usage is widespread. It is found in food packaging and textiles, is sprayed on agricultural fields through biosolids, and it seeps into groundwater at commercial sites, airports and military bases. Widely accepted estimates indicate that one-third of Americans drink water contaminated with PFAS, though more recent studies suggest that exposure to PFAS may be much higher.

New Jersey is no exception. In fact, New Jersey is among the top three states, behind Michigan and California, in the prevalence of PFAS. A 2015 study of Northeast waterways—the first to examine endocrine disruption in US national wildlife refuges— indicated estrogenic contaminants like PFAS were present in the water, having feminizing effects on male fish. Just last year, six towns in the Garden State discovered unsafe levels of PFAS in their drinking water. PFAS chemicals are estimated to be present in the drinking water of roughly 6% of 9.2 million New Jerseyans, with 34 community-based and 40 non-community-based water systems exceeding state thresholds for safe levels of consumption impacting over 500,000 people. Our densely-populated state is particularly vulnerable to PFAS and other toxic chemicals in our water, especially with high rates of waste, landfills, and industrial manufacturing contributing to high levels of PFAS in the water.

One of the biggest difficulties that PFAS presents is its impact on water utilities. In many cases, water utility companies are tasked with the burden of monitoring and reporting levels of PFAS in the drinking water, while simultaneously facing the consequences when levels of PFAS exceed the state and national thresholds. Utilities often must alert the public of unsafe levels, which can create alarm and tarnish the utilities’ public image; clean up the contamination or find a new supply of water; and pay the costs of both monitoring and cleanup—all the while not being responsible for the contamination in the first place. More often than not, these costs fall upon both utilities and the public’s water bills.

What New Jersey Is Doing To Protect Public Health

New Jersey leadership has been incredibly responsive and proactive in addressing PFAS contamination. The New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) recently established strict standards for PFAS in drinking water, as the first state to adopt a maximum contaminant level (MCL) for PFAS. New Jersey has an MCL for a few PFAS compounds: 14 parts per trillion (ppt) for PFOA and 13 ppt for PFOS. As of last year, the state requires all public water systems to be monitored for these chemicals. If you learn that PFAS have been detected in your drinking water above the New Jersey MCL, consult the current recommendations for limiting exposure from the US-EPA here.

In addition, the state is addressing the source of PFAS. In 2019, the NJDEP ordered five companies (3M, DuPont, DowDuPont, Chemours, and Solvay) to pay millions of dollars for cleanup of PFAS under the Spill Act, demonstrating the capacity for the state to enforce such measures and ensure adequate cleanup takes place. We need New Jersey’s strong leadership to continue as the state addresses this pervasive threat to environmental and public health.

Next Steps

Though we’ve gotten a good start here in New Jersey, there is much to do with regards to PFAS. A number of opportunities exist to address PFAS through investment in technology, funding for water quality remediation and treatment efforts, advocacy for stricter policy at the state level, enforcement of strict monitoring for contaminant levels, and holding polluters accountable. In Wisconsin, an innovative study lends us hope, as it has shown great success in decreasing concentrations of PFAS in the soil through the use of microbes which break down the compound. With the announcement of $1 billion of the state budget allocated to water infrastructure over the next five years, there are opportunities to direct funding to equip wastewater treatment facilities with the capacity to target PFAS and other contaminants in the water. At the same time, advocating for stricter standards for PFAS at the federal level can help to keep Americans safer from PFAS, following the model of New Jersey, which has one of the strictest limits on PFAS levels in the country. Currently, there is no national MCL, but the EPA recently proposed setting enforceable MCLs of 4 parts per quadrillion (ppq) for PFOA and 20 ppq for PFOS. A nationwide standard would also set the groundwork for enforcing PFAS limits under federal policy. Further, it is important to take steps to hold polluters accountable, requiring that those responsible for PFAS pay for remediation– not utilities or taxpayers. The bottom line is that keeping our communities safe from PFAS isn’t going to be easy, but if we work together and focus on transparency and creative solutions, keeping New Jersey waterways clean and healthy is attainable.

Ten Years After Sandy, a Look at Population and Housing Trends at the Jersey Shore

October 25th, 2022 by Tim Evans

Both before and after Superstorm Sandy, the trend at the Jersey Shore has been toward higher home values, a smaller percentage of housing units being occupied year-round, and an increasing presence of retirees among year-round residents. Is the Shore becoming a playground for the rich? And specifically rich retirees?

On the occasion of the tenth anniversary of Superstorm Sandy, we took the initiative to examine a looming question: how have New Jersey shore towns changed, in terms of the year-round vs. seasonal nature of their populations and housing stocks, in the wake of such a major flooding event? We are interested in towns that function as second-home or vacation-rental destinations and are dependent on seasonal visitors1, as opposed to year-round towns like Long Branch, Asbury Park, and Atlantic City, which face a different set of issues.

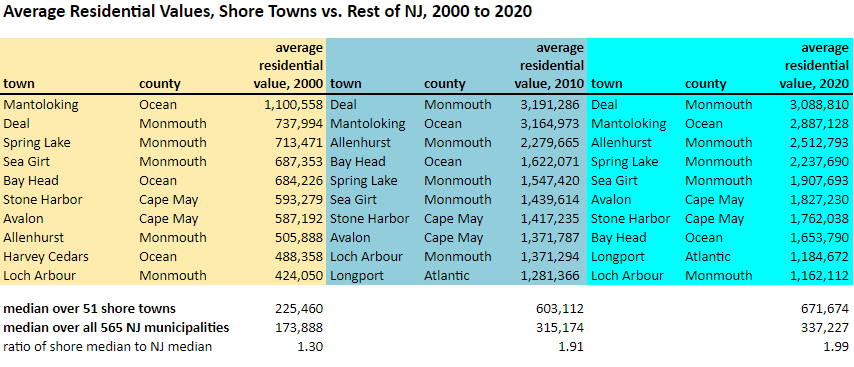

Home values in shore towns are expectedly high, but the differential is getting more conspicuous over time. Among the 51 towns, 38 had an average residential value in 2020 that was higher than the median municipal average of $337,2272 over all 565 NJ municipalities. This is similar to the situation in 2010, when 39 shore towns had average home values that exceeded the municipal median of $315,174. But the number is up from what it was in 2000, when 32 shore towns were above the municipal median. The upward trajectory of home values at the shore relative to the rest of the state was in place well before Sandy made landfall in 2012.

The values in these shore towns are not just high, they are significantly higher than the state median municipality’s average value. Among the 38 shore towns with 2020 average home values that exceeded the median municipal value, a full 25 of them had average values that were more than double the average value in the median municipality. Only 75 municipalities in the entire state exceeded this threshold, meaning that one-third of these high-value places statewide are shore towns, even though the shore towns make up fewer than one in ten municipalities overall. Among the 23 municipalities statewide having an average residential value of more than $1,000,000 in 2020, 13 were Shore towns, including eight of the top 11 (Deal, Mantoloking, Allenhurst, Spring Lake, Sea Girt, Avalon, Stone Harbor, and Bay Head).

Direct access to the ocean appears to be driving housing values. Most of the 13 Shore towns in which the 2020 average residential value is not higher than the median municipality’s tend to be the ones with substantial inland territory (e.g. Stafford, Ocean, and Eagleswood townships in Ocean County and the large mainland townships of Cape May County) and/or which front mainly on a bay rather than directly on the Atlantic (e.g. West Wildwood, Ocean Gate). In other words, most of the lower-value shore towns are places where few if any homes are within walking distance of the Atlantic Ocean itself, and even if you live “down the Shore,” you still drive to the actual beach. The only exceptions are Seaside Heights, Ventnor City, and Wildwood. By and large, if most or all of a town’s territory is on a barrier island, or it fronts on the ocean in the part of Monmouth County where there are no barrier islands, then its home values are going to be higher than average, often significantly higher.

Many of these homes are not lived in year-round. All 51 of these shore towns have vacancy rates that are higher than the statewide rate by virtue of how we are defining “the Shore,” but the trend is toward a greater percentage of housing units being occupied only seasonally, whether as second homes or as summer rentals. (Homes that are not occupied in the off-season are counted as “vacant” by the Census Bureau, even if they are lived in for part of the year.) Among the 51 shore towns, the median housing vacancy percentage has crept steadily upward, from 41.2% in 2000 to 48.6% in 2010 to 54.0% in 2020. So as of 2020, more than half of these shore towns are more than half empty in the off-season, hinting at a decline in the number of year-round residents.

As the percentage of housing units occupied only seasonally has trended upward, year-round populations have in fact trended downward. The 51 shore towns as a group saw their number of year-round households decrease by 2.6% from 2010 to 2020, even as the number of households statewide increased by 3.0%. Among the 51 towns, more than two-thirds (36) experienced absolute decreases in the number of households, and an additional five increased at a slower rate than the state. Most of the 10 towns in which the number of households increased faster than the statewide rate are among those with mostly inland territory, where home values also tended to be lower and where population growth is most likely not taking place in the oceanfront areas.

Year-round Shore residents are increasingly likely to be retirees. In 2000, the median percent of residents age 65 or older among the 51 shore towns was 22.3%, increasing to 25.0% in 2010 and further to 31.8% in 2020. The percentage of people age 65+ statewide increased from 13.2% in 2000 to 13.5% in 2010 to 16.2% in 2020, as the huge Baby Boom demographic cohort has begun aging into retirement, but the increases have been more dramatic at the Shore. In 2020, 14 of the 51 shore towns had a 65+ percentage of 40% or more, up from only eight in 2010 and only one such town (Cape May Point) in 2000.

Rising residential values, an increasing share of housing units being occupied only seasonally, and the increasing presence of people age 65 and older among year-round residents all point to Shore towns becoming increasingly off-limits for year-round occupancy for all but wealthy retirees. This raises fundamental questions about the future of the Jersey Shore. Given the risks from sea-level rise and climate change more generally, who will be able to live at the Shore on a part-time or year-round basis? Should there be a stable or growing population at all? Will only wealthy people be able to afford to move there? And will these wealthy residents be required to rebuild with their own money the next time disaster strikes? These are all questions that state decision-makers should be considering, perhaps as part of a much-needed update to the State Development and Redevelopment Plan.

__________________

1We define the 51 “Jersey Shore towns” as municipalities along the Atlantic coastline (as opposed to the Raritan and Delaware bays) in Monmouth, Ocean, Atlantic, and Cape May counties in which at least 10% of housing units were tabulated as “vacant/seasonal” by the Census Bureau in 2010. (The Census Bureau did not distinguish seasonally vacant units in 2020.) The full list of Shore towns by county:

Monmouth County: Allenhurst, Avon-by-the-Sea, Belmar, Bradley Beach, Deal, Lake Como, Loch Arbour, Manasquan, Monmouth Beach, Sea Bright, Sea Girt, Spring Lake, Spring Lake Heights

Ocean County: Barnegat Light, Bay Head, Beach Haven, Eagleswood Township, Harvey Cedars, Island Heights, Lavallette, Little Egg Harbor Township, Long Beach Township, Mantoloking, Ocean Gate, Ocean Township, Point Pleasant Beach, Seaside Heights, Seaside Park, Ship Bottom, Stafford Township, Surf City, Toms River, Tuckerton

Atlantic County: Brigantine, Longport, Margate City, Ventnor City

Cape May County: Avalon, Cape May, Cape May Point, Lower Township, Middle Township, North Wildwood, Ocean City, Sea Isle City, Stone Harbor, Upper Township, West Cape May, West Wildwood, Wildwood, Wildwood Crest

2 To clarify, each of the 565 municipalities has an average residential value, and the median of those 565 averages is $337,227

New Jersey Future Shapes and Supports New Flood Disclosure Legislation

October 21st, 2022 by Kimberley Irby

New Jersey Future’s Kim Irby and Peter Kasabach testifying at the August 11, 2022 joint Assembly and Senate Environment Committee hearing. Photo Credit: Hannah Reynolds

New Jersey has started down the path to join 29 other states that require home sellers to disclose past flood damages to potential buyers. Senate Bill 3110, which would benefit renters in addition to homeowners, was introduced last week at the Senate Environment and Energy Committee hearing on Thursday, October 6. This bill took shape two months after a joint Assembly and Senate Environment Committee hearing in which New Jersey Future testified on the need for robust flood disclosure legislation. In addition to New Jersey Future, Environment New Jersey and the Coalition for the Delaware River Watershed testified in support of flood disclosure transparency, while the New Jersey Apartment Association testified against the bill, suggesting a few changes to the portion relevant to landlords.

The destruction wrought by the remnants of Hurricane Ida in 2021 is still fresh in the state’s memory, and, even more recently, the remnants of Hurricane Ian caused flooding issues along the Jersey Shore just days before the committee hearing. Mandating flood disclosure is a common sense action for a state with coastal and inland flooding risks that are increasing due to climate change. Improving consumer transparency through this law will not only benefit current renters and homeowners, but also future generations who seek to locate in newly designated flood zones as FEMA and insurance companies update their maps. Ultimately, this legislative action will help save current and future New Jerseyans money and stress in the long term.

New Jersey Future worked through the Rise To Resilience Coalition and with the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) to advance specific flood disclosure requirements to both the New Jersey seller’s property disclosure statement and lease agreements. This work, also done in consultation with relevant stakeholders such as New Jersey Realtors, culminated in this bill, which will hopefully undergo a smooth process to reach the finish line.

Earlier this year, the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) published a report that estimated far higher damage costs to previously flooded homes in comparison to homes that had not been flooded. In response to that report, Pete Kasabach said: “New Jersey is the most developed state in the nation. This intense development coupled with the experiences of [Hurricanes] Sandy and Ida have demonstrated just how vulnerable our coastal and riverine communities are to flooding… It is well past time that New Jersey residents get the most complete and timely information about flood risks before they rent or purchase a home.”

The Senate bill was unanimously voted out of committee, with amendments, and now makes its way to the Senate floor, with an Assembly version assumed to be forthcoming. If the bill is signed into law at the Governor’s desk, as is widely anticipated before the close of this legislative session, New Jersey Future will work to ensure implementation is swift. It is past due time that all New Jersey homeowners or renters can consider the extent of their flood risk before choosing the place they will make their home.

Clean Water in the Garden State: Reflecting on 50 years of Progress and Challenges

October 18th, 2022 by Lindsey Sigmund

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the monumental piece of legislation known as the Clean Water Act (CWA). The CWA plays an important role in cleaning water pollution and protecting healthy waterways in the State of New Jersey for drinking water supply, healthy habitat for fish and wildlife, and economic and recreational activity. As we look ahead, we also acknowledge the work that still must be done to ensure that the CWA’s legacy is lived out in full.

In response to growing concerns over the quality of our nation’s bodies of water, the federal government passed the CWA in 1972, an amended version of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1948. The CWA established the structure for regulating the discharge of pollutants into the waters of the United States and regulated water quality standards of surface waters and wetlands. Prior to the passage of this landmark legislation, there was minimal regulation of what could be dumped into our waterways, which led to polluted rivers and lakes, contaminating many sources of drinking water and causing serious impacts for human health. Thankfully, today, it is unlawful for any pollutant to be discharged from a point source into navigable water without obtaining a permit.

Delaware River, Trenton, NJ, 2022. Photo Credit: Alyssa Zabinski, New Jersey Future

Since the 1970s, a significant volume of pollutants have been better managed, more lakes and rivers are fishable and swimmable, and the overall health of our waterways and wetlands has improved. However, progress has not been linear. Even today as we watch the Sackett v. EPA case unfold in the Supreme Court—where the classification of which bodies of water are considered waters of the United States (WOTUS) and thus can be regulated under the CWA is being determined—it is clear that the specifics of the CWA’s power have been largely contested. Over the past few decades, the Supreme Court and presidential administrations have restricted or reinstated protections for wetlands, streams, and other bodies of water. While battles may ensue on the federal level, New Jersey has been fairly consistent, going beyond minimum federal standards to protect the quality of our water resources.

One of the benefits of the CWA was the establishment of shared responsibility between the federal government and the states for regulation of waterways. For example, the CWA includes the option for states to assume the management of the Section 404 permit program to regulate dredge or fill material for certain waters not preempted by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. New Jersey is one of the few states that formally manage the permit program and acts as an example for other states working through clean water regulatory issues. While CWA enforcement is shared by the EPA and states, states have primary responsibility of ensuring compliance is achieved and programs are tailored to the unique needs of their communities.

A prime example of New Jersey’s leadership around clean water is the work of late Governor James Florio. As a congressman in the 1970s, Florio fought for the passage of the CWA. As governor, Florio was responsible for the Clean Water Enforcement Act (CWEA) of 1990, which solidified New Jersey’s commitment to water quality protections. The CWEA requires the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) to inspect permitted facilities and municipal treatment works annually. The CWEA is an excellent example of the reinforcement and reinstatement of the CWA on the state level.

The passage of the CWA has improved the quality of New Jersey’s waterways through regulating point source pollution, but nonpoint source pollution is still a looming concern. Non-point source pollution is caused by rainfall or snowmelt traveling over impervious cover, such as roads or roofs, carrying pollutants into storm inlets or directly into waterways. With a highly developed state such as New Jersey, retrofitting our impervious cover to include best management practices such as green infrastructure to decrease nonpoint source pollution and improve water quality and reduce flooding, is paramount.

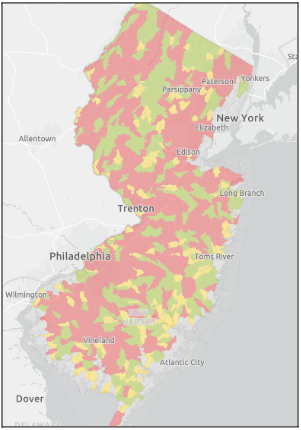

Impared streams in New Jersey shown in red (NJ Water Risk Equity Map, Rutgers University, Jersey Water Works)

In 2020 NJDEP published a new set of stormwater management rules that require the use of green infrastructure for new development. Prior to the rule change going into effect March of 2021, New Jersey Future, along with our partners, advocated for strengthening said rules to capture additional projects that increase impervious cover in order to better manage stormwater runoff across the state. With the reinforcement of sound research and public support, New Jersey improved its stormwater management rules and further increased protections of our water resources.

To improve current conditions, NJDEP anticipates approving a new and improved Tier A Municipal Separate Storm Sewer (MS4) permit early next year. The draft permit sets forth watershed level planning requirements for municipalities to address stormwater runoff. In response to the draft permit issued in July 2022, New Jersey Future issued comments and provided testimony to emphasize the need for faster implementation timelines and additional technical assistance and guidance from NJDEP to ensure permittees can reach compliance.

Sometimes rule updates, permitting updates, and other statewide initiatives are not always voluntary; at times the federal government gets involved. Through the National Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) Policy, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued requirements for all states with combined sewer systems to have their municipalities mitigate their combined sewer overflows through projects outlined in a Long Term Control Plan (LTCP). The LTCP outlines the most cost-effective manner to regulate CSOs to meet water quality standards. For the past few years, the Sewage Free Streets and Rivers campaign, staffed by New Jersey Future, has brought together grassroots organizations and residents of environmental justice communities with combined sewer systems to advocate for compliant LTCPs and robust community engagement around the planned water infrastructure projects. The LTCPs have been submitted to NJDEP, however these submittals have not been formally approved. The contents of these plans and their implementation will drive major infrastructure overhauls in 21 municipalities that currently experience overflow events that degrade their waterways. The results should drastically improve water quality, however the issue of funding and who foots the bill is ever-present.

In addition to permitting, NJDEP provides funding for local stormwater management projects through the 319(h) provision of the CWA. Earlier this year, NJDEP awarded $9.4 million in grants to municipalities, nonprofits, universities and others to fund local stormwater management projects. Municipalities including Newark, Trenton, and Jersey City received funding for tree plantings, green infrastructure, and other public improvements to manage stormwater to restore and protect water quality in their watersheds. Despite these funding sources, there is still a significant gap in funding, especially for overburdened communities. With the passage of the American Rescue Plan (ARP) in 2021, New Jersey allocated $300 million of its relief package to fund critical water infrastructure. However, additional outreach and technical assistance is needed to ensure that this infrastructure funding reaches overburdened communities. It is imperative that green infrastructure and other water infrastructure improvements are implemented in New Jersey’s overburdened communities, where improved management of our contaminated water legacy will make for healthier communities.

While great strides have been made in the past half of a century, many of our state’s waterways are still considered impaired, as indicated in the map above. Many of these waterways are contaminated from historic industrial uses, unregulated non-point source pollution, and mismanaged water and sewer infrastructure. All of these contributing factors are further exacerbated by climate change and related increasing temperatures and shifting precipitation patterns. As New Jersey grapples with our industrial past, surface and drinking water impairments, climate change, and environmental injustices, there is still a great need to progress further toward the original intent of the Clean Water Act. Here’s to the next 50 years of working toward fishable and swimmable waters for everyone in the Garden State!

New NJF Report Explores How to Promote Racial Integration in NJ Municipalities

September 22nd, 2022 by Tim Evans

Jersey City, NJ

New Jersey is paradoxically one of the most diverse and most segregated states in the nation. The state has grown more diverse over the last two decades, with its non-Hispanic white percentage shrinking from two-thirds of the state population in 2000 to a little more than half as of the 2020 Census, with notable proportional growth among Hispanic and Asian-American communities. But New Jersey’s macro-level diversity often does not translate into integration at the local level, and places that are integrated at the local level don’t always stay that way. New Jersey Future’s new report, “Promoting and Maintaining Racial Integration: Lessons from Selected New Jersey Towns,” examines what towns can do and have done to foster stable racial integration since 2000.

To explore possible answers, New Jersey Future summer intern Isabel Yip researched examples of New Jersey towns that have achieved and maintained an above-average level of diversity over two decades, to see what state and local leaders and policy makers might be able to learn from them. With advice from some of New Jersey Future’s professional colleagues who have experience in promoting integration and fighting discriminatory land-use practices, Isabel gathered information and insights from local officials, housing advocates, and engaged residents from a set of seven case-study municipalities that have engaged, in one way or another, in efforts to promote racial inclusivity.

These municipalities included:

- Montclair: The legacy of redlining recedes as demand grows for walkable and transit-oriented development–and raises concerns about displacement.

- Asbury Park: A town with a recent history of inclusion now struggles to maintain its diversity in a changing market.

- Cherry Hill: A former destination for “white flight” embraces diversity.

- South Orange and Maplewood: A coalition of residents from two neighboring towns demonstrates the value and importance of active and continuous engagement on integration.

- Jersey City: The state’s most diverse municipality finds that diversity is not a static concept.

- Pennsauken: Community engagement is important – and so is diversity in leadership.

Yip and New Jersey Future found that the concept of “stability” is elusive, and that promoting integration is an ongoing process that requires consistent attention and dedication from civic leaders and community members. Other themes that emerged from her fact-finding effort included policies like inclusionary zoning ordinances to maintain housing affordability, community engagement by public-facing agencies like police departments and school boards, and the creation of spaces in communities that promote casual interactions among people of diverse backgrounds. As the public becomes more aware of the degree to which local decisions about housing and land use affect who your neighbors are, the lessons and methods captured in this report indicate areas of success and improvement for municipalities and communities to adopt or avoid.

Read the full report here.

Next Steps for Warehouse Planning – and Regional Planning More Broadly

September 21st, 2022 by Tim Evans

The State Planning Commission has adopted new warehouse siting guidance. The next step should be to translate the principles articulated in the guidance into a map indicating the best places for future warehouse growth to take place.

The State Planning Commission has adopted new warehouse siting guidance. The next step should be to translate the principles articulated in the guidance into a map indicating the best places for future warehouse growth to take place.- In preparing the map, the Office of Planning Advocacy should coordinate with the New Jersey Department of Transportation, which is preparing a Freight Plan that will address freight as it moves over the transportation network.

- State efforts to address warehouse growth are serving to highlight the importance of statewide planning—and the long-dormant State Development and Redevelopment Plan—in channeling future growth in a way that makes efficient use of infrastructure and resources while also preserving the state’s quality of life.

The State Planning Commission at its Sept. 7 meeting officially adopted the Warehouse Siting Guidance drafted by the Office of Planning Advocacy (OPA) earlier this summer, intended for use by municipalities in deciding how best to plan for warehouse developments. With the rapid growth of the goods-movement industry in New Jersey in recent years, more municipalities will need help sorting through the issues involved, which the officially adopted Warehouse Siting Guidance is intended to provide.

While the guidance document offers much-needed assistance to local officials who are struggling to anticipate the likely effects of warehouse development, none of its recommendations are mandatory—New Jersey remains a “home rule” state where local governments have authority over land-use decisions. For municipalities that may be interested in operationalizing some of the concepts laid out in the guidance, OPA staff are working on a model ordinance and will be seeking feedback on it in the coming months.

Goods movement is a key pillar of New Jersey’s economy. The wholesale trade (NAICS code 42) and transportation and warehousing (NAICS codes 48 and 49) sectors of the economy account for one out of every eight jobs in the state, the highest percentage among the 50 states. By addressing the land-use needs and impacts of a major statewide industry, the warehouse guidance document serves to bring back into the spotlight the importance of regional planning and OPA’s role in promulgating the New Jersey State Development and Redevelopment Plan (“State Plan”), the policies of which are referenced throughout the warehouse guidance.

A logical next step for OPA would be to translate their guidance into a map indicating the locations of potential development and redevelopment sites that best meet the warehouse-siting criteria articulated in the guidance, similar to how the State Plan map illustrates the principles that animate the Plan playing out on the ground. OPA should coordinate with the New Jersey Department of Transportation (NJDOT), which is currently working on an update of its Statewide Freight Plan (the most recent edition of which dates to 2017), to identify sites that are optimally situated near the regional transportation network and best able to accommodate the truck traffic that large warehouse buildings attract. If the Freight Plan is concerned with moving freight from one place to another, while a state warehouse plan would be focused on the spaces occupied by freight while it is standing still, each process should be able to inform, and be informed by, the other. Sites that appear well-suited to warehouse development from a transportation standpoint could then be compared to map layers illustrating other relevant constraints, like the locations of prime farmland or of lower-income communities already suffering from poor air quality.

A statewide warehouse map and its accompanying analysis could serve as a stand-alone product or could be incorporated into a broader (and overdue) revision of the whole State Plan, which has not been updated since 2001. The point of the State Plan has always been to anticipate future growth and determine how and where to accommodate it in a way that makes the most efficient use of state resources while also preserving the state’s quality of life. These are the questions that shippers and industrial real estate developers are presently confronting with respect to warehouses, but the questions are not unique to the goods-movement industry.

Much has changed about New Jersey’s development landscape in the last 20 years. Targeted growth areas, transportation corridors, land preservation priorities, and redevelopment opportunities all need to be updated to reflect current conditions. Future growth strategies also need to reflect threats from climate change, which Superstorm Sandy, Hurricane Ida, and other major weather events have brought to the fore in the two decades since the State Plan was last updated. If state agencies are to target infrastructure investments and development incentives—whether for warehouses, residential growth, or any other type of development—to places where they best advance the state’s vision of its own future, a new edition of the State Plan would give them an up-to-date baseline from which to work. For these reasons, and more, New Jersey Future supports a robust and inclusive update of the outdated State Plan.