New Jersey Future Blog

Five Community Planning Initiatives To Solve Problems and Save Money

June 6th, 2023 by Chris Sturm

Local officials face a rapidly changing world due to forces beyond their control. Impacts from the pandemic, climate change, and the racial reckoning cannot be ignored, nor can new state government requirements, ranging from housing to flood resilience. But by investing in community planning initiatives, municipal and county leaders can solve problems, save money, and strengthen their communities. Five especially pressing community issues in 2023 are: fulfilling Mount Laurel requirements for affordable housing, growing communities without displacement, navigating real estate market shifts, adapting to climate change, and decreasing pedestrian fatalities.

Mount Laurel Requirements for affordable housing. New Jersey municipalities are experiencing accelerated construction of deed-restricted affordable housing and associated market-rate housing, as described in a new report, Dismantling Exclusionary Zoning: New Jersey’s Blueprint for Overcoming Segregation, Between 2015 and 2022 New Jersey’s Mount Laurel housing requirement resulted in the construction of nearly 22,000 new deed-restricted affordable housing units and an additional 50,000 multi-family housing units in “Mt. Laurel associated projects”. The pace of affordable housing production will increase as additional approved units are built. Meanwhile, these new housing units are creating much-needed homes for people and families across the state.

The next phase of affordable housing requirements, called “the Fourth Round,” will commence on July 1, 2025. The 350 or so affected municipalities can begin planning now for Fourth Round requirements so they can increase supply, variety, and affordability of housing stock and remain an attractive place for households of all types and incomes. Proactive municipalities are identifying the most advantageous sites and getting them ready. Win-win-win sites are well-located near jobs, schools and shopping; redevelop vacant or underutilized properties rather than natural lands; are served by water infrastructure, and are resilient to flooding. Sites in downtown locations can also boost economic development. But some of the best sites have obstacles to housing production that take time to resolve. Municipalities that begin now will find themselves better able to steer future housing construction than those that wait until deadlines loom. Adopting an inclusionary zoning ordinance that requires a share of new housing units be affordable gives municipalities another head start.

Inclusive Communities. Affordable housing in affluent areas represents just one side of the coin when it comes to reducing the high racial and economic segregation of New Jersey’s communities. It can be complemented by attracting market-rate development to poorer communities—but only if those developments benefit, rather than harm, existing residents and businesses. For example, new market-rate development can spark a wave of investment that escalates rents and property taxes, which in turn displaces residents and small businesses. Redevelopment planned without community input can undermine neighborhood cohesion and quality of life.

Proactive cities are finding ways to ensure residents benefit from new investment. Jersey City, Newark, and others have adopted inclusionary zoning ordinances that require creation of affordable housing units as a part of new development projects. This ensures some units remain affordable to those with lower incomes even as real estate values rise. If well structured, Community Benefit Agreements can ensure that developers provide tangible benefits tailored to local needs. For example, they can guarantee jobs for local residents, deliver investments in desired neighborhood amenities, and ensure local input into project designs. Community Benefits Agreements (CBAs) are now required for certain projects funded through two of the New Jersey Economic Development Authority’s tax incentive programs. Cities can employ many additional strategies, including giving existing residents a strong voice in decision-making.

Real Estate Market Shifts. The coronavirus pandemic accelerated market forces that are reshaping communities. The shift to remote work and hybrid schedules have cut office occupancy rates, affecting the vitality of downtowns, office parks and corporate campuses, and undermining restaurants and other businesses that cater to workers. The surge in e-commerce has also hurt the already shrinking storefront retail sector. Some of these trends may revert to pre-pandemic levels as the pandemic recedes, but others are likely to stick, and local governments need to adapt.

Cities and towns are beginning to seek ways to convert vacant office and retail spaces for new uses, such as housing, which is in short supply in New Jersey. Suburban office parks and malls offer opportunities for creating new mixed-use centers where none existed before, by repurposing existing buildings and by adding new buildings and uses on surface parking lots.

E-commerce has also fueled a spike in demand for warehousing, superimposed on top of trends in international trade that are increasing the volume of goods arriving at the state’s major ports in North Jersey. The rising demand for logistics facilities of all sizes has caught many communities by surprise. Affected municipalities can employ the tools provided in the Warehouse Siting Guidance from the Office of Planning Advocacy in order to proactively plan for and locate warehouse development in a manner that avoids negative impacts.

At the same time, New Jersey’s population is aging, and many municipalities are working to design their communities in ways that support older adults. Changes that help us remain in our communities as we age also benefit people of all ages. These include having a greater range of housing options, providing equitable access to open spaces and other facilities, supporting downtown economies, and improving transportation and walkability.

Flooding and other Climate Change Impacts. Due to sea level rise in coastal areas, and more intense precipitation events statewide, many developed areas face more frequent and more intense flooding. In response, the NJ Department of Environmental Protection has updated projections for precipitation and sea level rise and municipal permits addressing water quality, particularly due to stormwater runoff. The Department is also considering multiple regulations that will impact municipal stormwater management, development in flood prone areas, and re/development standards.

Prudent municipalities are investing resources to assess their vulnerabilities to climate change and understand new regulatory and planning requirements. A climate change-related hazard vulnerability assessment, now required in the land use element of municipal master plans, is a foundational first step in local climate adaptation; stay tuned for detailed guidance from New Jersey Future later this year. Strategies to limit flood damage to property and people include better stormwater management, more resilient design standards, and in some places, transitioning away from high hazard areas through zoning changes and NJDEP Blue Acres buyouts. In order to fund infrastructure improvements that address flooding, many towns are exploring creation of a stormwater utility.

Pedestrian Safety. In a 2022 report, New Jersey ranked as the 19th most dangerous state for pedestrians, with 870 pedestrian deaths in the five-year period between 2016 and 2020. The most dangerous roads in New Jersey for pedestrians are usually four- or six-lane highways in developed areas with a large amount of commercial businesses but few sidewalks and intersections. At the same time as pedestrian deaths are rising, state policy encourages greater reliance on walking and biking since they are climate-friendly transportation options that emit no greenhouse gas emissions. As long as our crosswalks put pedestrians in the crosshairs, we will fail to see broad adoption of walking as a primary mode of zero emissions transportation through our communities.

Pedestrian Safety. In a 2022 report, New Jersey ranked as the 19th most dangerous state for pedestrians, with 870 pedestrian deaths in the five-year period between 2016 and 2020. The most dangerous roads in New Jersey for pedestrians are usually four- or six-lane highways in developed areas with a large amount of commercial businesses but few sidewalks and intersections. At the same time as pedestrian deaths are rising, state policy encourages greater reliance on walking and biking since they are climate-friendly transportation options that emit no greenhouse gas emissions. As long as our crosswalks put pedestrians in the crosshairs, we will fail to see broad adoption of walking as a primary mode of zero emissions transportation through our communities.

Proactive communities in New Jersey are retrofitting streets, including main streets, as “complete streets” that are consciously designed to be safe and inviting for all users–not only drivers, but also pedestrians and cyclists. They can obtain resources on complete streets from the New Jersey Department of Transportation (NJDOT) and the Bicycle and Pedestrian Resource Center and adopt a model complete streets policy. They should also apply for project grants from the following local aid programs: Bicycle and Pedestrian Planning Assistance, Safe Routes to School, and Safe Streets to Transit.

Community Planning Success Stories. It’s all too easy to put off community planning projects until nagging problems become crises. Thankfully, leading county and municipal officials across New Jersey offer successful models for tackling affordable housing, inclusionary communities, real estate market shifts, climate change impacts, and pedestrian safety. Each of these topics, and many others, will be explored by expert practitioners at in-depth workshops at the 2023 Planning and Redevelopment Conference on June 21–23. Additional panels will focus on the role that the state and federal government play in planning and redevelopment, including one featuring an expected update to the New Jersey State Development and Redevelopment Plan. Seize the day and invest in planning to solve problems and save money.

New Report Highlights Link Between Local Zoning and Housing Affordability

May 17th, 2023 by Tim Evans

New Jersey is experiencing a housing affordability crisis, one that hits lower-income households particularly hard. But New Jersey has a unique set of laws requiring local governments to zone for affordable housing, and a new report demonstrates that these laws work when enforced.

New Jersey is one of the most racially and economically segregated states in the nation, and also has among the country’s highest housing costs, due in part to exclusionary local zoning that limits the types of housing that are permitted. Zoning limitations on both the supply and variety of housing options drive up costs, and put many places out of reach for lower-income households. Barriers to affluent, low-density zoned neighborhoods remain high, especially for Black households who experienced redlining and still experience forms of systemic racism. Because of the correlation between race and income, exclusionary zoning is a prime driver of both racial and economic segregation.

Fair Share Housing Center’s new report, Dismantling Exclusionary Zoning: New Jersey’s Blueprint for Overcoming Segregation, demonstrates how enforcement of court-imposed requirements resulting from the Mount Laurel State Supreme Court decisions in the 1970s and 1980s, which mandate local governments to provide affordable housing, is addressing regional inequities. In particular, it illustrates how the production of affordable units accelerated since supervision of municipal compliance was turned over to the courts following the 2015 dissolution of the Council on Affordable Housing (COAH), the state agency created by the Fair Housing Act in 1985 to implement requirements, but which became ineffective.

Not only does the report show that New Jersey’s system works when it is actually enforced, it also shows how local zoning changes designed to comply with affordable housing requirements have had a much broader effect, stimulating the production of more market-rate multi-family housing types that benefit middle-class and working-class households who are also increasingly facing the affordability crunch. Towns often meet their obligations by producing affordable units as part of “inclusionary” developments that also include market-rate units, and these inclusionary developments are almost always multifamily developments, which increase the supply of rental units in a municipality.

By focusing on local zoning and on the increased production of multifamily housing, this report creates a new starting point for the discussion of how New Jersey can increase supply, variety, and affordability of housing stock and remain an attractive place for households of all types and incomes. We look forward to building on this work to ensure that more people can afford their homes in well-planned, smart growth communities that are open and inclusive of all races and incomes.

Rolling Along: Why New Jersey Should Join Other States and Offer an E-Bike Incentive Program

May 17th, 2023 by Kimberley Irby

Electric bicycles, along with programs intended to incentivize their adoption, are rolling out across the country and New Jersey can’t afford to be left behind in this transportation revolution. Transportation emissions, which account for more than a third of all total greenhouse gas emissions in the state, are a critical target for climate change mitigation, necessitating the use of every tool to help us drive less. E-bikes in particular have huge potential to increase transit equity, since they add a transportation option for those who can’t afford a car, choose not to have one, or are unable to drive. However, even e-bikes can be prohibitively expensive, which is why incentive programs are particularly important for supporting low-income individuals with their purchase and ultimately reducing how much we drive. New Jersey’s density is an asset in encouraging bicycle and e-bike mobility and infrastructure and all the more reason to implement a statewide program encouraging more e-bikes on our streets. This analysis examines successful e-bike incentive programs at the state, county, and local levels across the nation to better inform a comprehensive and successful incentive program in New Jersey.

Electric bicycles, along with programs intended to incentivize their adoption, are rolling out across the country and New Jersey can’t afford to be left behind in this transportation revolution. Transportation emissions, which account for more than a third of all total greenhouse gas emissions in the state, are a critical target for climate change mitigation, necessitating the use of every tool to help us drive less. E-bikes in particular have huge potential to increase transit equity, since they add a transportation option for those who can’t afford a car, choose not to have one, or are unable to drive. However, even e-bikes can be prohibitively expensive, which is why incentive programs are particularly important for supporting low-income individuals with their purchase and ultimately reducing how much we drive. New Jersey’s density is an asset in encouraging bicycle and e-bike mobility and infrastructure and all the more reason to implement a statewide program encouraging more e-bikes on our streets. This analysis examines successful e-bike incentive programs at the state, county, and local levels across the nation to better inform a comprehensive and successful incentive program in New Jersey.

Read the full report here.

Eliminating Lead Service Lines: Filling the Funding Gap, One Drop at a Time

May 11th, 2023 by Gary Brune

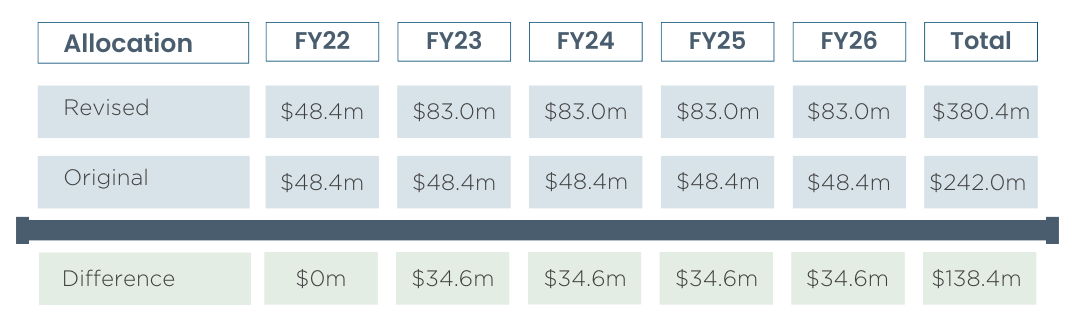

In early April 2023, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced a major change in the allocation of federal funds provided through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) to remove lead service lines (LSLs), replacing a distribution scheme that failed to properly recognize states with older housing stock where the lion’s share of LSLs are likely to exist. This was welcome news to New Jersey, as the state’s allocation will more than double from 1.7% to 3.8%, increasing annual funding for LSL replacement by $35 million (73%), from $48 million to $83 million. This could potentially yield as much as $138 million in additional funds for LSL replacement (LSLR) over the remaining four years of the BIL program. In total, New Jersey seems in line to receive $380 million through fiscal year 2026.

To judge this properly, some context is important. Ranked eighth among states based on its estimated 350,000 LSLs, New Jersey faces a total potential price tag of $2.8 billion to completely remove this public health scourge, which poses a particular threat to young children. While $380 million certainly sounds like a lot of money, it actually represents less than 14% of New Jersey’s total need.

As required by federal law, the initial BIL allocation in fiscal year 2022 was not based on the known or suspected location of LSLs, but rather on all water and wastewater needs (e.g., treatment plants, pumping stations), as reported by states in EPA’s Drinking Water Infrastructure Needs Survey and Assessment (DWINSA) completed in 2018. However, that distribution bore no relationship to the actual need for LSLR projects. As a result, the $48 million appropriated to New Jersey in fiscal year 2022 provided a benefit of only $138 per resident, second lowest amount in the country. A total of 23 other states with significantly fewer LSLs received at least $1,000 per capita. In an extreme example, California received $250 million in fiscal year 2022, or $3,838 per capita for the relatively few LSLs thought to exist in the Golden State.1

As enacted by Congress in 2018, America’s Water Infrastructure Act provided a potential solution by requiring states to estimate their LSLs as part of the 2022 DWINSA survey. However, since most states benefited from the EPA’s original allocation, it was not clear how soon this change would be implemented, and advocacy seemed destined to be a steep, uphill climb.

To its credit, EPA expedited the survey results, ensuring that the revised allocation influenced the funding distribution for the second year of the five year BIL program. And as is true with most successful advocacy efforts, collaboration and partnerships helped amplify the call for change. As part of the Clean Water, Healthy Families, Good Jobs campaign, which advocates for additional water infrastructure funding, New Jersey Future (NJF) joined forces with organizations such as the NJ Laborers Union, the NJ Business and Industry Association, and the NJ Utilities Association. NJF also worked with the Environmental Policy Innovation Center, the Natural Resources Defense Council, and a national forum of advocates from other states with heavy LSL concentrations (e.g., IL, NY, and OH). Information sessions with New Jersey’s congressional delegation, as well as substantive comments submitted to EPA, stressed why it was so important from an efficiency and environmental justice standpoint to stop short changing the states with the greatest need.

Looking to the future, there may be other ways to increase the financial assistance that New Jersey can provide for LSLR projects. The points noted below could serve as the next logical targets for advocacy to address NJ’s funding gap on this important issue:

- Unspent State Revolving Fund (SRF) Balances—To encourage prompt spending, EPA requires states to contract SRF funds for water and wastewater projects within two years, after which balances are reallocated to other states that are ready to spend. The federal BIL funds are administered through the SRF program, and though it is too early to judge how quickly they will be obligated for LSLR projects, it is interesting to note that approximately 4% of all SRF funds were not committed from 2011–2020.2 If that pattern holds true for the $15 billion authorized by Congress for LSLR, $600 million could be available for reallocation among the states.

- Galvanized Service Lines—Unlike New Jersey, some states do not mandate the complete replacement of galvanized service lines, despite the fact that they are a known source of lead in drinking water. Therefore, EPA’s current funding formula does not take those lines into account. Since EPA estimates that New Jersey may have over 180,000 galvanized lines, this places the state at a distinct disadvantage for having done the “right thing” to protect public health.

- American Rescue Plan (ARP)—In New Jersey, over $1 billion in federal ARP funding remains unallocated. While $300 million in ARP funds was appropriated to water infrastructure last year, that was largely directed to combined sewer overflows. In his Fiscal Year 2024 Budget Message, Governor Murphy committed to increase support for water infrastructure from ARP and other sources, providing another potential solution to get the lead out of drinking water.

__________________

1IIJA Lead Service Line Replacement Funding Distribution (nrdc.org)

2Uncommitted State Revolving Funds (duke.edu)

Opinion: Car-Free Inspiration From an Overseas Adventure

May 1st, 2023 by Chris Sturm

This piece originally appeared in Streetsblog, USA on April 14, 2023

For four months last fall, my lifestyle changed dramatically when my husband and I lived car-free. As life-long suburbanites, we have always driven a lot to get around. I was the mom-in-the-minivan, and am now the professional-in-a-Prius. But when we took an overdue sabbatical, we lived near universities in three developed countries — England, Germany, and Japan — where everything we needed was within easy reach by foot, bike, bus, or train. This experience convinced me that New Jersey can and should pull out the stops to deliver more of these options for all of its people — young and old, commuters and job-seekers, the affluent, and those who cannot afford a car.

Our Car-Free Experience

Our first stay was in Cambridge, England, a small city of 145,000 inhabitants. Cambridge is called England’s “city of cycling,” and we quickly figured out that renting bikes was our best option, whether for a two-mile commute, running errands, and exploring the countryside. There were initial terrifying moments as we adjusted to riding on the left-hand side of the road, learned the signs for where cyclists are (and are not) allowed, and navigated traffic. Thankfully, bus and car drivers go slowly and defer to cyclists. Special street features kept us safe, including my favorite: a dedicated zone at traffic lights just for cyclists, so they can go in front of the cars while they wait for their very own traffic signal, which allows them to pass through the intersection first. Meanwhile, I managed to indulge my lifelong obsession for pastries and a new penchant for fish and chips without gaining a pound.

Parents commute with special cargo bikes that have a big cart in front for kids and groceries and our 80-year old landlords cycled to shop and go to church.

In early October, we moved to Stuttgart, Germany, a growing mid-size city of 630,000. Notwithstanding its fame as an automotive headquarters (Porsche, Mercedes-Benz), Stuttgart has an amazing downtown for walkers and a robust bus, subway, and local train network. Our apartment was located two blocks from downtown, and literally on top of a subway stop (complete with a first floor bakery). Because the city is so compact and destinations are clustered near stations, we never needed a ride-share, even for unplanned medical visits, suburban musical theater, downtown opera and ballet. I bought groceries every few days at nearby stores and seductive indoor and outdoor markets, loading up my backpack and building bone density as I walked home. I used the public bike share program and rode for exercise through a beautiful urban park, walked to my favorite restaurants, and conveniently hopped on the regular, reliable bus when met with the inconvenience of rain.

Effective land use controls not only prevent development from sprawling into the German countryside but ensure that most destinations are close at hand in the town center, as in Rottweil shown here.

In mid-November we landed in Tokyo, the world’s second largest metro area with 23 million residents. Our neighborhood, located between Tokyo University and Ueno Park, surprised us with its low-rise buildings, bikeability, and livability. Despite Tokyo’s reputation as a sprawling, busy city, parents use cargo bikes and kids walk to school. Armed with Google Maps on my smartphone, I happily walked four minutes to the subway station and traveled all over the city. Street crossings are safe, and drivers and pedestrians alike follow the rules. My Japanese friend let me try her e-bike, which I found to be really cool. However, I chickened out on renting one, which I hope to change soon. Our neighborhood was full of tiny, cheap restaurants ranging from a humble, mouthwatering ramen place to cozy izakaya (pubs) with cold beer and grilled fish, to an excellent western bakery, but with all the walking, my high cholesterol actually diminished.

In mid-November we landed in Tokyo, the world’s second largest metro area with 23 million residents. Our neighborhood, located between Tokyo University and Ueno Park, surprised us with its low-rise buildings, bikeability, and livability. Despite Tokyo’s reputation as a sprawling, busy city, parents use cargo bikes and kids walk to school. Armed with Google Maps on my smartphone, I happily walked four minutes to the subway station and traveled all over the city. Street crossings are safe, and drivers and pedestrians alike follow the rules. My Japanese friend let me try her e-bike, which I found to be really cool. However, I chickened out on renting one, which I hope to change soon. Our neighborhood was full of tiny, cheap restaurants ranging from a humble, mouthwatering ramen place to cozy izakaya (pubs) with cold beer and grilled fish, to an excellent western bakery, but with all the walking, my high cholesterol actually diminished.

Even in Tokyo’s skyscraper-filled downtown hubs, pedestrians are safe and comfortable on the streetscapes. Some districts offer Hokousha Tengoku, or “pedestrian paradise,” on Sundays, including the Ginza and Sagenjaya, shown here.

Secret To Success: What Cambridge, Stuttgart and Tokyo Do Right

These three places — small, medium, and giant — all deliberately prioritize the development patterns and transportation systems that deliver great options for getting around. The three places we visited have:

- Compact development and a mix of uses so every day trips — to work, school, shopping, the park — are short.

- Lots of green space in public parks, rather than in private yards.

- Streets designed for all users, with ample sidewalks, all kinds of bike lanes and paths, benches, signage, traffic signals, etc.

- A culture of “Sharing the Road” rather than cars being “King of the Road.”

- Less car parking, mostly underground or in garages. Plenty of bike parking.

None of this happens on its own. Consider these ambitious walk-bike-ride initiatives in the news:

- The City of Cambridge is considering a congestion charge proposed by the Greater Cambridge Partnership to reduce car traffic and raise revenues for better bus service. It’s highly controversial, but London and Birmingham offer precedent. Meanwhile, the Cambridge Cycling Campaign actively advances the needs of cyclists.

- To return transit ridership to pre-pandemic levels and lower the cost of living, the German government offered a cheap (nine euros (about $10) per month) transit pass last summer. It was wildly popular and saved an estimated 8 million tons of carbon emissions by reducing car trips. The government now plans to launch a permanent “D-ticket” on May 1 for €49 per month to offer “a strong argument to switch from the car to a climate-friendly means of transit,” at an estimated cost of €3 billion annually.

- Japan’s largest private railway firm, JR East, recently announced an ambitious goal to expand its property asset management model in order to better ensure the financial sustainability of its transit systems. JR East and other Japanese railway firms generate substantial funds for their system operations from station-area real estate. Transit-oriented development not only generates income for rail operations, but also grows ridership.

New Jersey Has a Head Start on Becoming a National Mobility Leader

New Jersey is well-positioned to act on lessons from abroad. One reason is that New Jersey can “place-make” as well as anywhere. This year, I’ve had the pleasure of meeting people in Haddonfield, Highland Park, New Brunswick, Somerville, Trenton, and Bordentown, all of which boast a walkable town center. On weekends we go further afield: biking along the spectacular Hudson River waterfront and grabbing a bite to eat in Hoboken or Jersey City; visiting transit- and beach-accessible Ocean Grove and Asbury Park; and walking between Newark Penn Station, Harrison’s Red Bull Stadium, and the Ironbound’s food scene.

When it comes to improving walk-bike-ride opportunities, New Jersey is not starting from scratch. The state’s public transportation system of buses, rail, and light rail is the nation’s largest statewide system, and serves nearly one million riders per day. New Jersey is the nation’s densest state, and has a legacy of historic walkable villages, towns, and cities.

The local leaders with whom I’ve spoken are excited about the prospect of developing a robust walk-bike-ride network in their municipality and are hungry for help with project planning and design, the essential first step to accessing state and federal capital funds for construction.

Keeping the Car-Free Magic Alive Now that I Am Home

My sabbatical felt life-changing. The experience of getting around by walking, biking and riding provided triple benefits: reducing my carbon footprint, improving my personal health, and freeing up time. Now that I am home, I’ve asked myself: what will I do differently?

While eliminating automobile travel or moving to a dense mini-downtown are off the table for now, I’ve committed to a more modest switch to going “car-light” by eliminating two car trips a week. Because we live in New Jersey, we have quality transit options that I am using more often, like taking NJ Transit train service to meetings in New Brunswick. Even though the trip takes twice as long, I get 30 more minutes of productive time to read or answer emails, and 15 minutes of joyful walking and fresh air. The dollar cost is identical, and my carbon footprint is reduced. Alternatives to driving are worth pursuing: as I learned in my time abroad, traveling “car-free” is living more “care-free.”

Access to Parks is an Environmental Justice Issue

April 19th, 2023 by Hannah Reynolds

Conversations around environmental justice (EJ) and social determinants of health are commonly focused on the inequities that are present in underserved communities: the dangerous developments and contaminants. Often, the focus of environmental justice efforts is on remediating the lead and forever chemicals like PFAS found in the drinking water of low-income communities, or cleaning up the massive superfund sites or improving air quality near freeways that are often sited in communities of color. So naturally, there is a limited discourse in the environmental justice movement on what is missing in communities that have been historically marginalized, especially when it comes to things taken for granted as amenity, like parks.

Camden, New Jersey

“To provide an overarching perspective, there are 100 million people in the United States—of which 28 million are children—who don’t have access to a park within a ten-minute walk of their homes. That’s an equity statement,” said Scott Dvorak, the Associate Vice President and New Jersey State Director of the Trust for Public Land. “In communities of color, the parks people do have access to are, on average, half the size and serve five times as many people as those in privileged areas. In these parks, the programming needs and demand are higher, but the entities responsible for maintaining the parks often have restricted resources.”

Nearly a third of Americans do not have easy access to parks, making access to parks and public space a luxury in our country. However, the data shows striking disparities in park access for people in underserved communities and from marginalized backgrounds. An estimated 76% of people living in low-income communities of color live in places deprived of nature, with communities of color experiencing roughly triple the rate of nature deprivation compared with predominantly white communities. Consequently, people living in low-income, majority-minority communities disproportionately experience firsthand the impacts of the destruction of nature related to air and water pollution, waning biodiversity and the spread of diseases, and the impacts of climate change, to name a few. In New Jersey, Governor Phil Murphy has moved to cut admission fees to state parks, with the state charging no state park fees in 2022 and seeking to do the same in summer 2023. By reducing cost barriers to visiting parks, New Jersey has taken great strides toward creating more accessible parks for all New Jerseyans to enjoy. But why is access to parks so important for promoting environmental justice?

The accessibility, availability, and funding of parks plays a crucial role in health outcomes. One major function of parks for health is to foster access to open space for exercise and physical activity. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that young people get at least an hour of physical activity per day and that adults do at least an hour and a half of aerobic activity each week to stay healthy. However, the majority of Americans do not get enough exercise, with only 25% of adults meeting these recommendations and with nearly a third of American adults engaging in no exercise in their leisure time.

Lack of physical activity is associated with a number of physical health concerns including obesity, high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol, heart failure, stroke, osteoarthritis, reproductive and bladder issues, and pregnancy complications, as well as many mental health concerns like depression, eating disorders, and low self-esteem. Overall, the trends of insufficient exercise and physical health concerns within the population hold serious ramifications for the wellbeing of Americans.

However, access to parks offers opportunities for health outcomes to be improved, with the availability and accessibility of green outdoor spaces for recreation acting as social determinants of health. When Americans obtain increased access to parks and advertisements about park offerings, events, and amenities, studies show that exercise can increase in frequency by nearly 50%. At the same time, energy levels, weight loss, and flexibility generally improve with heightened access to a place for exercise. Further, mental health is significantly associated with access to parks and nature, with reports of heightened attention, mood, and cognitive functioning, as well as reduced stress.

Beyond this, the benefits of accessible parks extend to community health, with social cohesion and economic outcomes—such as lowered healthcare spending and heightened financial security—are also found to be correlated with park accessibility. In other words, reliable access to parks and open outdoor spaces promotes exercise and consequently boost health outcomes in an otherwise too-sedentary population. Therefore, park equity can and should be considered a matter of environmental justice just as much as contaminated water or toxic construction sites.

Beyond supporting health outcomes, green spaces can benefit the natural environment, curbing urban heat island effects, supporting stormwater management naturally, and enhancing air quality. Reduced air pollution related to parks can lower rates of asthma, which disproportionately impacts people of color, and has been found to be associated with the spread and mortality of COVID-19. Altogether, it becomes clear that low-income areas with high sprawl development—where the expectation of driving limits access to parks and green spaces for low-income people—can negatively impact health outcomes, posing a serious inequity for marginalized and underserved populations—which begs the question, why aren’t we investing more in parks?

Beyond mere access to green space, equity issues around parks extend to quality and upkeep of these public spaces, as well as the safety of walking or biking to a given park. While two-thirds of Americans have access to parks within a 10-minute walk, according to Scott Dvorak, there remains vast disparities around quality, size, demand, and maintenance of parks. Many parks situated within low-income communities of color are often poorly maintained, dangerous, understaffed, or underfunded. Investing in existing parks to create safe, clean, resilient parks for all to enjoy will meet the demands of the communities they serve. Not only that, but maintenance of green spaces saves money. One study reports that for every one dollar spent on creating and maintaining park trails, three dollars of healthcare spending can be saved.

However, the ability to walk to a park within a ten-minute radius does not guarantee that the infrastructure and streets to get there are safe, clean, or even present. Especially in low-income communities, there may not even be sidewalks connecting local people to such parks. Therefore, if a park is only truly accessible by driving, this will limit who can enjoy a park, preventing many low-income people from spending time at the park. Though New Jersey ranks second in the country for most land dedicated to park spaces, as the nation’s most densely-populated state, urban sprawl, disinvestment in urban areas that largely consist of people of color and people with lower socioeconomic status, lack of connectivity, and poor planning all have contributed to determining which New Jerseyans have easy and safe access to parks, which is certainly not equitable or inclusive for all. Through all of this, it is clear that equity around park access is dependent upon not only the presence of parks, but also their quality.

“Accessibility is not only, of course, about race and income. It’s also about ability, age, special needs, and making parks accessible for the whole spectrum of human condition.” Scott Dvorak of the Trust for Public Lands put it well. It is crucial to not only advocate for increased availability of parks, but also to ensure that parks have proper funding, maintenance, staffing, and connectivity with the community, in order for local peoples to enjoy all the benefits of public spaces and parks. At present, too many Americans lack access to nearby parks and the environmental and health benefits they offer, demonstrating that park access can act as a predictor of health outcomes. Ultimately, if we are to achieve an environmentally-just world, equitable and reliable access to parks and open spaces for all people is an essential step.

From Federal Dollars to State Investment: Understanding Technical Assistance for Water Systems

April 17th, 2023 by Diane Schrauth

At New Jersey Future’s Planning and Redevelopment Conference in June 2022, New Jersey Commissioner of Environmental Protection, Shawn LaTourette, emphasized the historic funding opportunities for NJ flowing from the federal government and implored attendees, “If you don’t have a grant writer on staff, hire one. If you do have one, hire a second.” LaTourette concluded his remarks by stating his desire for New Jersey to seize the opportunity for federal funding, and to position itself well for any additional rounds of funding.

New Jersey Future at the CIFA Summit on Water Infrastructure. From left to right: NJF Funding Navigator Program Manager Aoi Morel, Environmental Policy Innovation Center Funding Navigator Director Denise Schmidt, US Water Alliance CEO Mami Hara, NJF Policy Director of Water Diane Schrauth, and US Water Alliance Director of Policy and Government Affairs Scott Berry.

New Jersey Future (NJF) is partnering with a national organization, the Environmental Policy Innovation Center, as its on the ground partner in New Jersey for its national Funding Navigator program. The Funding Navigator will provide technical assistance to help water systems and municipalities—particularly those serving overburdened communities—access federal and state funding for water, sewer and stormwater issues. New Jersey’s Funding Navigator will formally launch later this month (April 2023).

As NJF highlighted in a blog from November, New Jersey has a myriad of water infrastructure needs, including addressing combined sewer overflows, achieving full lead service line replacement by 2031, and increasing stormwater requirements. New Jersey was an industrial powerhouse in the 19th century, which led to rapid development and construction of infrastructure to accommodate a growing population. The many systems that comprise our statewide water infrastructure are, in many cases, over a century old, and in dire need of replacement. With the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) there is roughly four times as much funding available for water infrastructure projects as usual. This funding is sorely needed, with at least a $30 billion price tag for water infrastructure improvements over the next 20 years in New Jersey.

National research shows that smaller communities and communities of color are less likely to access federal and state water infrastructure funding. The Funding Navigator will work with water systems and municipalities servicing those communities to help access that funding by facilitating connections to finance and funding streams, technical assistance, and community engagement.

If you’re interested in learning more about NJF’s Funding Navigator once it’s launched, please fill out this form for our team to follow up with you.

As we work to get our New Jersey Funding Navigator off the ground, we want to help folks understand the various technical assistance programs available at the federal, regional, and state levels. NJF will be partnering with many of these entities, which are also in the process of getting their programs up and running.

National Technical Assistance Providers

The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has provided funding to a set of national and regional organizations through its Environmental Finance Centers program to help communities access funds for infrastructure projects. National Technical Assistance Providers and their likely areas of emphasis:

- Environmental Policy Innovation Center (Sand County Foundation is the fiscal sponsor)— lead service line replacement and small-to-midsize systems

- Moonshot Missions—needs assessment

- Rural Community Assistance Partnership (RCAP)—rural systems

- U.S. Water Alliance—large systems

Communities interested in requesting free EPA water assistance can fill out a simple interest form on their Water Technical Assistance program page.

Regional Technical Assistance Providers Serving New Jersey

The Syracuse University—Environmental Finance Center works with communities in New Jersey, New York, and Puerto Rico to help access funding and financing for municipal water infrastructure. Partners will include Cornell College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Moonshot Missions, New Jersey Future, Quantified Ventures, and RCAP Solutions.

Technical Assistance Programs in New Jersey

- The EPA’s Lead Service Line Replacement Accelerator Program will provide targeted technical assistance services to underserved communities to make progress on replacing lead pipes that pose risks to the health of children and families. A consultant will work with these communities directly with support from the EPA. The accelerators will collectively work in 40 communities across the four states—Connecticut, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin—to accelerate lead service line projects by supporting the development of:community engagement plans, lead service line inventories, lead service line replacement plans, State Revolving Fund funding applications. NJF is a partner in this program.

- New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP)

- NJDEP offers no-cost assistance using its contracted technical service providers to water systems for various activities such as engineering services, program navigation, and financial and needs assessments. Water systems can apply using this Technical Assistance Request Form.

- The Technical Assistance Program (NJTAP) will help disadvantaged or overburdened communities to identify lead service lines, develop asset management and capital improvement plans, and identify sources of state and federal funding to assist with important water quality improvement projects. NJTAP will provide support via a consulting firm that will work directly with water systems to address lead in drinking water.

- New Jersey Infrastructure Bank (I-Bank) will be providing technical assistance to help communities access the Water Bank. This program will resource a pool of qualified engineers to provide assessments of public water facilities, including fiscal condition and inventory of assets. NJF was selected as part of the I-Bank’s Early Engagement Assistance Services Pool that will work with the engineering consultants.

The success of New Jersey’s Funding Navigator program will require ample relationship building with agencies and municipalities to extend the greatest available resources to New Jersey communities, especially those serving low-income residents. NJF’s Funding Navigator team is ready and able to assist communities large and small with achieving our common goals of improving public health and resilience in the face of climate change by funding improvements to New Jersey’s water infrastructure. Please reach out to Lee Clark (lclark njfuture

njfuture org) with questions or fill out this interest form, and keep an eye out for New Jersey’s Funding Navigator launch later this month!

org) with questions or fill out this interest form, and keep an eye out for New Jersey’s Funding Navigator launch later this month!

Transportation for Everyone: Designing Safe, Sustainable Options for Women

March 17th, 2023 by Hannah Reynolds

Last year, New Jersey Future explored how women and gender nonconforming people face disproportionate obstacles when accessing public transit, biking, or walking as forms of transportation. We found that 65% of women-identifying people have experienced street harassment in their lives and that 99% of the NYC public transit riders who reported sexual harassment on the subway identified as female. We learned that people who identify as women face a higher risk of assault when walking, biking, or riding public transit, and that low-income women often face the highest dependence on these modes of transportation. While these alternatives to driving cars are typically more sustainable and affordable than their gas-powered counterparts, the potential costs of walking, biking, or taking public transit for women—namely the inherent threat to personal safety—could be taken as an implication that cars are the safest option for women-aligned people to get around. However, cars are unsafe for everyone: drivers, pedestrians, bikers, and especially, people assigned female at birth (AFAB).1 As cars get bigger and heavier, drivers of smaller, more sustainable cars face heightened risk in collisions. At the same time, drivers of larger vehicles are more prone to rollover crashes and hitting pedestrians due to increased blindspots and limited fields of vision. Beyond this, private automobiles manufacturers boast annual safety awards as they deliver safer and safer automobiles, it is important to acknowledge that automobile safety is also subject to the same biases that prioritize men found throughout our economy and society.

Last year, New Jersey Future explored how women and gender nonconforming people face disproportionate obstacles when accessing public transit, biking, or walking as forms of transportation. We found that 65% of women-identifying people have experienced street harassment in their lives and that 99% of the NYC public transit riders who reported sexual harassment on the subway identified as female. We learned that people who identify as women face a higher risk of assault when walking, biking, or riding public transit, and that low-income women often face the highest dependence on these modes of transportation. While these alternatives to driving cars are typically more sustainable and affordable than their gas-powered counterparts, the potential costs of walking, biking, or taking public transit for women—namely the inherent threat to personal safety—could be taken as an implication that cars are the safest option for women-aligned people to get around. However, cars are unsafe for everyone: drivers, pedestrians, bikers, and especially, people assigned female at birth (AFAB).1 As cars get bigger and heavier, drivers of smaller, more sustainable cars face heightened risk in collisions. At the same time, drivers of larger vehicles are more prone to rollover crashes and hitting pedestrians due to increased blindspots and limited fields of vision. Beyond this, private automobiles manufacturers boast annual safety awards as they deliver safer and safer automobiles, it is important to acknowledge that automobile safety is also subject to the same biases that prioritize men found throughout our economy and society.

While driving—unlike walking, biking, or taking public transportation—allows women-aligned people to get from place to place with minimal threat of harassment or assault, studies show that cars too are not designed with women’s safety in mind. Presently, safety features like seat belts and airbags and even dashboards are created to best fit the safety needs of someone the size of an average man in the 1970s, an outdated measure which has resulted in disproportionate injuries in people who are AFAB, aging adults, people who are overweight or obese, children, and other diverse human bodies. Beyond cisgender women being smaller on average than men, the anatomical differences between biological males and females heighten the risk of serious injury and death for people who are AFAB in crashes. People with female anatomy tend to sit further forward when driving, so that their legs can reach the pedals, and they tend to sit more upright in order to see over the dashboard. This means that biologically-female people are considered “out of position drivers,” meaning that most people assigned female at birth (over half the population) tend to sit outside the position that is optimized for driver safety—increasing their risk of internal injury in frontal collisions. As a result, a biological woman in the driver’s seat is 73% more likely to be seriously injured if the car crashes and 17% more likely to die than a male driver. Women are also more likely to experience whiplash in rear-end collisions especially, given their lighter weight, less muscle composition in the neck and upper torso, and varying spinal columns compared with men. Slow-speed crash tests with biological women indicate that they are thrown forward harder and faster than biological men in rear-end collisions, given their smaller size and body composition. Overall, car design prioritizes male drivers in terms of safety and structure, posing heightened risks for cisgender women.

While safety features in cars are predominantly designed for average-sized men, the disregard for women’s safety in automobile manufacturing extends beyond design: crash testing also prioritizes male safety. Crash-test dummies, first introduced in the 1950s, are most commonly based off of the average cisgender male—at 5 feet, 10 inches tall and weighing 168 pounds, with the muscle composition and column associated with biological males. It was not until 2011 that ‘female’ crash dummies were first implemented, but these dummies are merely modeled after male dummies scaled down to the 5th percentile. As a result, ‘female’ dummies fail to accurately model the average female geometry (shape and form of the torso), muscle mass and distribution, ligament size, spinal alignment and vertebrae spacing, body sway and dynamic responses to trauma, and bone density. All of these factors impact how a biologically-female body experiences a car crash, which without adequate testing and design of appropriate safety features can give way to serious injury and death.

Even more appalling, however, are the outdated assumptions about women-aligned people who use automobiles for transportation. Despite the fact that as of 2019, more than half the licensed drivers in America are woman-aligned people, ‘female’ crash dummies are predominantly tested in the passenger and back seats. There is an assumption—dating back to the 1950s, but implemented in 2011, when ‘female’ crash dummies were first mandated—that those identified as women are not primarily drivers, so prioritizing safety in passenger positions is sufficient in safety testing. At the same time, using a baseline ‘average’ size from 1970 is unrealistic and inadequate, as more drivers today are overweight or obese. Further, testing pregnant crash dummies is not mandated by the US, despite the existence of dummies modeled after pregnant people—a glaring safety concern for both birthing people and their unborn children. Car crashes are the number one cause of fetal death from maternal trauma, yet 62% of third-trimester parents cannot fit in a standard seatbelt. Through all this, it appears that car manufacturers continue to perpetuate outdated understandings of female autonomy and fail to consider and design for the needs of biologically-female drivers, effectively putting women’s safety at risk.

All in all, women experience disproportionate safety risks in most, if not all, forms of transportation, whether mass transit, walking, biking, or driving. As a result, it is crucial to address the systemic barriers and threats which endanger women’s lives as they move from place to place, by building infrastructure that is accessible and reliable for the needs of women. While there has been some movement by legislators to require enhanced safety testing measures for biologically-female drivers—including the Furthering Advanced and Inclusive Research for Crash Tests Act (FAIR Crash Tests Act) proposed in 2021—there is a long way to go until women are adequately protected in vehicles, both in practice and in the law. Whether creating wide, well-lit streets for walking and biking, increasing reliability and accessibility of mass transit options like trains, buses, and the metro, or designing EVs to also meet women’s safety needs, there needs to be urgent investment and legislation around women’s safety and reliable, accessible, and sustainable transportation.

__________________

1Language shapes the way we think and understand the world. Note: In this blog, the terms “woman” or “female” are predominantly used in a limited sense, focused on people born with biologically-female anatomies. In recognition of Women’s History Month, this blog is focused on the experiences of biological, cisgender women, but these findings also are applicable to transgender men and nonbinary people assigned female at birth. The safety concerns related to automobile crash testing and design primarily impact people with female anatomy, but we recognize that anatomy and gender identity are distinct and not necessarily correlated. Therefore, we use language such as: assigned female at birth, biologically female, cisgender women, etc. to be as equitable as possible. We also refer to people who can give birth as pregnant or birthing people, to recognize that not all people with the ability to give birth identify as female. When referring to those identifying as female (regardless of anatomy), we specify woman-identifying or those who identify as female, which includes transgender women.

Metuchen’s Downtown Revitalization: An Award-Winning Catalyst for Smart Growth

March 16th, 2023 by Hannah Reynolds

“The Woodmont Metro at Metuchen Station was a catalyst for further redevelopment in downtown Metuchen… Having residents living downtown has resulted in a remarkable growth of restaurants, making downtown Metuchen a highly popular regional dining destination. New retail and service businesses have also opened creating a vibrant, active downtown,” explains Jay Muldoon, Director of Special Projects with the Borough of Metuchen. “The changes are tangible and significant—downtown Metuchen is now alive with people, visitors, residents, and customers. It can be argued that the genesis for this transformation was the Woodmont Metro at Metuchen Station project, which included the creation of the Town Plaza public space.”

Home to nearly 14,000 community members in Middlesex County, Metuchen is rapidly becoming a New Jersey destination in its own right, after years of being primarily known for being a NJ Transit stop on the way into New York City.1 The town’s downtown, centered around a recent development called The Woodmont Metro, is easily within reach of Metuchen’s NJ Transit Station, which services over 11,000 commuters each weekday. The town offers a dense suburban feel, with 77% of community members owning their own homes and with a multitude of parks, coffee shops, and restaurants within walking distance.

Photo of the winter market at Metuchen Town Plaza, full of tents hosted by local shops. The downtown offers a walkable, pedestrian-friendly space for events and gatherings. Used with permission of the Borough of Metuchen and Metuchen Downtown Alliance.

“It’s been a great boom for the local economy here and has been a nice renaissance for the town. I grew up in South Edison. We used to just cut through Metuchen as a pass-through to other parts of Edison. Now when I come through Metuchen, there’s a reason for me to come down here and stop. I can have dinner here. It’s not just a pass-through anymore,” said Luigi Beltran, owner of Luigi’s Ice Cream in downtown Metuchen.

In 1981, Metuchen first released a 20-year analysis and plan called Metuchen 2001, collaborating with a Rutgers University urban design studio. This effort sought to plan for efficient land use along Main Street, to produce a more active, safe, and lively downtown. By 2001, Metuchen was declared a Transit Village in only the second year of the state’s Transit Village program.

New Jersey Future first honored the Borough of Metuchen in 2004 for its Town Center Design and Development plan with a Smart Growth Award. Again in 2017, Metuchen received a Smart Growth Award recognition for its Woodmont Metro at Metuchen Station, a project designed to help implement the plan. The repeated recognition that Metuchen has received for the development of its downtown and train station is indicative of the community value that can come from transit-centered revitalization and smart growth, offering an example for commuter towns and transit villages across the state to follow moving forward.

Photo from before Metuchen prom at Metuchen Town Plaza. Students gather to take a selfie in the downtown plaza area. Used with permission of the Borough of Metuchen and Metuchen Downtown Alliance.

Among the most notable steps toward smart growth and good urbanism in the Metuchen Station redevelopment project was the Borough’s move to rezone the downtown to allow residential units above businesses. Not long after Woodmont Metro was constructed in 2016, the developer constructed “The Hub,” a mixed-use project with roughly 80 apartments and first-floor retail, made possible by the new zoning ordinances. This, coupled with efforts to create a more walkable, pedestrian-friendly streetscape and various in-fill development in the downtown, established a more connected, walkable community in Metuchen that provides access to retail, food, businesses, and mass transit alike. At the same time, the Borough has successfully redeveloped more than 100 acres of land of abandoned, decommissioned, and otherwise underutilized former warehouses, auto dealerships, lumberyards, and even freight lines. Now, these spaces have been revitalized for mixed-use enterprises, whether as office and commercial space or as residential units. Walking in downtown Metuchen today, one can find art collectives and dance studios, fitness centers and yoga studios, cafes and sushi bistros, and boutiques and salons—many of which are women and minority-owned businesses.

Photo of people breakdancing at Metuchen Town Plaza. Used with permission of the Borough of Metuchen and Metuchen Downtown Alliance.

“Woodmont Metro was the catalyst for over $170 million of investment. More than 150 new businesses were started since 2016, of which 89% are still in business today. The average resident brought $14,231 in spending according to market analysis. When Woodmont Metro and all other development is added up, the 387 apartments helped to generate $5.5 million of new spending each year,” explained Isaac Kremer, former founding executive director of the Metuchen Downtown Alliance and former employee with Woodmont Metro. He went on to outline the significance of this data for Metuchen’s downtown community, vibrancy, and energy. “The Town Plaza has subsequently become the heart of the community hosting events throughout the year. Walkability has increased with more people choosing to ditch the car and enjoy walking our streets and sidewalks in Metuchen. Lastly, market research shows over 70% of customers are coming from outside of Metuchen. So by making Metuchen more livable, we’ve also become a regional destination.”

The Borough’s redevelopment not only has supported activity and color in the downtown of Metuchen, but also has fostered resilience in the community, even through the COVID-19 pandemic. Muldoon explained, “Through a strong collaboration between the Borough and our Special Improvement District, the Metuchen Downtown Alliance (MDA), programs were put in place to enable businesses to not just survive, but many to thrive through the pandemic. The MDA secured funding through various grants, including Main Street New Jersey, that was used to support restaurants and other businesses’ efforts to pivot to new ways of doing business. The MDA assisted businesses in seeking pandemic relief funds and worked with the Borough to create outdoor dining areas in public spaces and in Borough right of way areas. As a result, very few businesses closed because of the pandemic and many new businesses decided to open in Metuchen due to the strong support provided to our business community.”

Photos of Pearl St. parking lot in downtown Metuchen before redevelopment, where Woodmont Metro is now located. This former parking lot is now vibrant with life and community. Used with permission of the Borough of Metuchen and LRK.

The Woodmont Metro at Metuchen Station has redeveloped a former commuter parking lot into a parking garage with additional retail space and nearly 300 housing units, 15% of which is affordable housing. The project has also established a half-acre public outdoor space for community use, which became a particularly significant part of the community amidst concerns around indoor public gatherings during the COVID-19 pandemic. The outdoor space is frequently used for weekly farmers’ markets, among other community events.

Photo from inaugural Pride on the Plaza at Metuchen Town Plaza during summer 2022. Used with permission of the Borough of Metuchen and Metuchen Downtown Alliance.

Through this sustained and widespread effort at development and redevelopment, Metuchen has emerged as a real community center, as opposed to merely a stop on the way to an end destination. In NJF’s review of notable smart growth projects over the past two decades, Metuchen’s downtown revitalization efforts demonstrate a uniquely sustained and successful commitment to community development and resilience, embodying the meaning of this award. Metuchen shows us how orienting development around transit increases the benefits for local community members and businesses, but also for those from adjacent towns that may lack such a rich and accessible commercial downtown.

Metuchen’s downtown still has room to grow. Former Founding Executive Director of the Metuchen Downtown Alliance Isaac Kremer highlighted opportunities for improvement, explaining how retail and work spaces could be better integrated at the ground level, making Metuchen’s downtown more integrated and walkable. “[W]e lost a ground floor retail opportunity connecting Main Street with Whole Foods and the surrounding commercial property. There was some discussion about the ground floor ‘terrace’ apartments being made into live-work spaces. Instead these are standard apartments and do not add to the ‘interesting walk,’ as Jeff Speck called it in Walkable City. That prevents people circulating further out. Additionally, the opposite side of the street is still surface parking lots and undeveloped. Hopefully these will be redeveloped some time soon, so we have buildings framing each side of the street.”

The Borough’s Jay Muldoon sums it up well. “Downtown Metuchen’s renaissance is not complete. Metuchen is well on its way to becoming the regional hub of commerce it once was, and is already a preferred destination for area residents for dining, professional services, retail and arts. The Borough continues to work on plans for the creation of the Metuchen Arts District to be anchored by the Forum Theatre, which will enliven another part of our extended downtown. Some might say the best is yet to come.”

__________________

1This blog is derived from an internal review conducted by New Jersey Future on our Smart Growth Award winners from the past 20 years. Metuchen, having won two awards for their downtown revitalization efforts in 2004 for their plan and again in 2017 for its implementation, is a standout example of smart growth in New Jersey.

New Jersey Future (NJF) at the White House

February 6th, 2023 by Hannah Reynolds

NJF Policy Manager Deandrah Cameron at the White House Summit on Accelerating Lead Pipe Replacement.

On January 27, 2023, New Jersey Future’s very own Deandrah Cameron—policy manager and backbone staff for Lead-Free NJ and the Jersey Water Works’ Lead in Drinking Water task force—represented NJF and the state of New Jersey at the White House Summit on Accelerating Lead Pipe Replacement, part of the Biden-Harris administration’s Lead Pipe and Paint Action Plan. Deandrah was one of many leaders in water policy invited to attend the event, which brought together experts from four states (New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, and Wisconsin) to learn about and collaborate to address the issue of lead in drinking water across 40 communities. The Lead Service Line Replacement Accelerators program is a collaborative effort between the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and state partners across the four states represented at the summit. State partners include mayors and government officials, utilities, and water policy advocates, nonprofits, and funders, as well as the US Department of Housing and Urban Development, and the NJ Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) and equivalent departments from across the four states. New Jersey and NJF were invited in recognition of our leadership on lead issues. Over time, New Jersey, along with the three additional states, will serve as a model for other states grappling with the chronic issue of lead in the drinking water.

Vice President Harris speaking at the White House Summit on Accelerating Lead Pipe Replacement.

“We got to hear from Vice President Harris, who dubbed herself a water policy nerd—we were all really excited to hear her go on and on about the topic we are so passionate about,” Deandrah shared, remarking on her experiences at the summit. Another speaker who particularly stood out was a woman named Deanna Branch, an advocate with the Milwaukee-based Coalition for Lead Emergency, whose nine-year-old son had experienced lead poisoning, which kicked off her work in organizing for clean drinking water. “As someone working in policy who is not always on the ground in communities, it was good to see and hear from someone who is impacted by lead and who is excited to see that we are taking this issue so seriously. Hearing Deanna speak was a major highlight from the summit,” remarked Deandrah, reporting back on the highlights of her trip to the White House.

Milwaukee-based Coalition for Lead Emergency advocate Deanna Branch speaking with her nine-year-old son by her side.

At the summit, the work being done in the state of New Jersey to address lead in drinking water was elevated as a model of what lead service line replacement can look like. “New Jersey is seen as a pioneer in the field of water quality, and it’s good to see our state considered as a leader,” Deandrah explained of NJ’s leadership role in the collaborative effort toward lead pipe replacement in the four states. During the summit, mayors served on panels alongside state representatives and utilities, including Director Kareem Adeem of Newark’s Department of Water and Sewer Utilities and NJDEP Commissioner Shawn LaTourette. Deandrah recounted watching NJ representatives speak, stating that “Being from New Jersey, it was cool seeing Kareem Adeem from Newark—one of the people we work closely with on the JWW Lead in Drinking Water task force—and the commissioner of NJDEP talking about what the City of Newark is doing and offering support for other utilities and cities, all on a national platform.”

From left to right: NJDEP Commissioner Shawn LaTourette, NJF Policy Manager Deandrah Cameron, Mayor of East Newark Dina M. Grilo, and Newark Department of Water and Sewer Utilities Director Kareem Adeem.

In his remarks on a panel at the summit, Kareem Adeem offered sound advice based on his experiences in Newark in lead service line removal. “Communication, communication, communication. You may not always get it right, but that doesn’t mean you stop. You continue to communicate. You continue to, you know, acknowledge those times when you made a mistake, you should always acknowledge it, but you continue to move forward… Overall, the political collaboration with the local government, the county, and the state, [it made it so] we were able to [remove the lead service lines].” Of the work done by Adeem and many other leaders in the City of Newark, Vice President Harris remarked, “Other cities and other families and children around our country will benefit from the work you did right here.”

From left to right: Clean Water Action Campaigns Director Lynn Thorp, Environmental Policy Innovation Center (EPIC) Chief Strategy Officer & Director of Water Strategy Maureen Cunningham, and NJF Policy Manager Deandrah Cameron.

All in all, NJF appreciates the opportunity for Deandrah to represent NJF amongst water policy leaders from across the country. Deandrah shared some final reflections which illustrate the significance of the White House Summit personally, for our partners, and for the state of New Jersey. “In my role at NJF, I have the opportunity to hear from two great collaboratives: Jersey Water Works and Lead-Free New Jersey. I work with some of the smartest people in the state on lead issues, and to see their work elevated and validated in having New Jersey Future be selected as a partner for the White House Summit on Accelerating Lead Pipe Replacement is incredible. One of the goals of our Get the Lead Out partnership is to convene all representatives quarterly. Currently, I meet with the experts in our collaborative monthly and we get in the weeds on lead, so to be able to elevate our mission across states and share our expertise is so powerful. I never imagined taking the work beyond the walls of NJ, so to get to work across four states and 40 communities shows that our work is transcending state lines. I used to have a goal of every city in New Jersey being like the City of Newark and having lead-free drinking water, but now I have a vision of all 40 cities in the partnership, and all cities in the US. My enthusiasm and vision and goals around water quality have expanded because we’re now working at a national level.”