New Jersey Future Blog

New Jersey Needs More Housing, and Municipalities are on the Front Lines

July 30th, 2024 by Chris Sturm

Without a safe, stable place to call home, how can people achieve any personal goals?” asked Department of Community Affairs (DCA) Commissioner Jacquelyn Suárez. Her opening remarks kicked off the session, “Housing: What’s Next in New Jersey?” at the 2024 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference. Suárez described the agency’s “housing first” model, including programs to facilitate home ownership, prevent homelessness and support walkable downtowns.

Four panelists joined Suárez to discuss solutions to the housing crisis, which affects people of all races and many incomes. Poverty is statewide, explained Peter Rosario, President and Chief Executive Officer at La Casa de Don Pedro, citing applications from mostly white families for free and reduced school lunches in suburban Toms River. But he added, “the biggest density problem in this state is single-family homes, which are weaponized against black and brown communities.”

“Traditional housing that is affordable is being priced out,” said Michele Delisfort, Principal and Managing Partner, Nishuane Group LLC, noting, “Even with a college degree, it’s difficult to afford a home.” Josh Bauer, Staff Attorney at the Fair Share Housing Center declared, “Affordable housing is a racial justice issue.” Stephen Santola, Executive Vice President and General Counsel, at Woodmont Properties asked, “The entry-level cape is getting knocked down and replaced by a larger home selling for so much more—Where are the mid-level people going to live?”

Some solutions will come soon—next June—from the municipalities that must adopt new plans to build affordable housing under the Mount. Laurel doctrine. A new law enacted earlier this year, A4/S50, streamlines and clarifies the process; it assigned tasks to DCA, which Commissioner Suárez described:

- Issue non-binding affordable housing obligations for each municipality in October 2024.

- Gather and publish more robust municipal data on Affordable Housing Trust Funds and the number and type of affordable units that have been constructed.

- Develop criteria to streamline compliance and give municipalities more certainty.

She encouraged the audience to contact her office with concerns and suggestions.

Local officials face many challenges in siting affordable units. “How can communities plan and zone for affordable housing that advances smart growth while managing local opposition?,” asked moderator Chris Sturm, Policy Director for Land Use at New Jersey Future. Commissioner Suárez called for better communication. “People hate change, but elected officials need to have open conversations, and if they know the type of person who will live in affordable housing, it will help,” offering the example of a nurse who needs housing in the community where they provide healthcare. “Education is primary,” added Michele Delisfort, encouraging local leaders to explain redevelopment to stakeholders early and often and to get their feedback. She emphasized understanding the community, and compelling developers to deliver well-designed projects. Josh Bauers argued for a change in perceptions: “A four-story building will NOT detract from the property values of surrounding homes,” adding that people should view “multi-family” housing as “residential”. Steve Santola cited Princeton’s ordinance allowing Accessory Dwelling Units as a test case, which, if successful, could be a statewide remedy.

“People hate change, but elected officials need to have open conversations, and if they know the type of person who will live in affordable housing, it will help” –Department of Community Affairs Commissioner Suárez

All NJ municipalities urgently need practical tools to design and plan for housing. New housing should not only be affordable but climate resilient and in great neighborhoods where it’s easy to get around without a car and near parks and plazas. Panelists recommended:

- State support to increase local capacity for public outreach and early investment in comprehensive planning.

- Mandatory high-quality training for planning boards, in place of today’s lax program.

- Best practice tools, such as FAQs on planning and redevelopment, “Density by Design – NJ Style”, and templates for hosting effective planning board and governing body meetings.

- The ability to use more affordable housing trust fund monies for presentations and messaging, supported by revised DCA rules.

- Timely technical assistance that reaches towns early, before they begin their lengthy schedule of monthly meetings.

Affordable housing success stories like the Taylor Vose inclusionary housing project in South Orange can help local officials envision solutions for their community. See New Jersey Future’s Smart Growth Award winners for more.

Audience members raised broader affordability concerns, like the role consumer debt plays in limiting access to credit. Commissioner Suárez highlighted the difficulty municipalities face in hiring employees like emergency medical service staff and inspectors who do not earn enough to afford to live where they work. Panelists recommended holistic approaches to making New Jersey affordable—like using regionalization to lower the cost of local government (Suárez ), working with banks and financial institutions (Delisfort), and changing rental and mortgage requirements to focus on on-time rental payments (Rosario).

When asked, “What’s next for housing in 2050?” speakers shared visions that can inspire residents and local leaders today:

- More sustainable housing that relates to the environment, and communities that are better connected. -Michele Delisfort

- Look to student housing to see what’s next. -Stephen Santola

- Better public transportation. -Josh Baurs

- Open air spaces, plazas, and walkability, like those found in other parts of the world. -Peter Rosario

- Walkable, liveable places transformed from past industrial giants and malls. More community-centric places with multi-generational housing. -Commissioner Suárez

Chris Sturm closed the session by announcing that New Jersey Future and partners are launching a collaborative new initiative, Great Neighborhoods for All, which seeks to achieve visions like these because everyone in New Jersey deserves an affordable home in a community that’s a great place to live.

The Great Neighborhoods for All group is advancing three separate but interrelated initiatives:

- Building a statewide movement of local campaigns that advance inclusive, well-planned, and well-designed housing projects.

- Empowering local governments to solve pressing problems, such as addressing accelerating displacement of renters and meeting Mount Laurel Fourth Round deadlines with better planning for neighborhoods.

- Changing state policy in the next eighteen months.

To learn more, email Chris Sturm (csturm njfuture

njfuture org) or Alesha Vega (avega

org) or Alesha Vega (avega njfuture

njfuture org) .

org) .

Stormwater Pays No Mind to Municipal Borders—Why Should You?

July 30th, 2024 by Chris Sotiro

“Stormwater follows watershed boundaries, not political boundaries,” said Dr. Dan Van Abs, Professor at Rutgers University, during the 2024 New Jersey Planning & Redevelopment Conference (PRC). Many of New Jersey’s 564 municipalities grapple with flooding issues. For some, it is not uncommon for as little as three inches of rainfall to grind daily life to a halt. As average precipitation and severe weather events increase due to climate change, New Jersey will experience more frequent flooding. As the most densely populated and most developed state in the country, our flooding woes are amplified by the propensity for stormwater runoff to pollute sources of drinking water. In order to prevent chronic flooding and water quality impairments, municipalities must cooperate on a regional scale to improve their shared watersheds.

A panel of experts in the stormwater and watershed management spaces explored the benefits of a regional approach to watershed planning at the 2024 NJPRC, sponsored by New Jersey Future and the New Jersey chapter of the American Planning Association. The session “Save Money, Talk to Your Neighbors: The Case for Regional Watershed-Based Planning” featured Dan Van Abs, Professor of Professional Practice at Rutgers University, Jim Cosgrove, President of One Water Consulting, Lindsey Sigmund, Program Manager at New Jersey Future, Mike Pisauro, Policy Director at The Watershed Institute, Nicole Miller, Principal of MnM Consulting, and Tom Dallessio, Executive Director of the Musconetcong Watershed Association.

As Mike Pisauro of The Watershed Institute explained, a major component of the new Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System (MS4) Permits—applicable to every municipality across the state—is the development of a Watershed Improvement Plan (WIP). While it is important to identify avenues for reducing water quality impairments, municipalities are limited in their ability to holistically address the watershed they occupy. Whereas a municipality can be affected by poor watershed management upstream, it cannot enforce improvement projects outside of its own local borders.

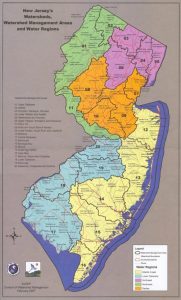

New Jersey’s Watershed Management Areas (WMAs)

Some municipalities have simply been dealt a bad hand of cards, like Manville Borough, which sits at the bottom of the North and South Branch of the Raritan River. During Hurricane Ida ten inches of rain over a three-hour period led to a record-high 27.66-foot crest of the Raritan River, leaving some residents to experience flood waters reaching the second floor of their homes. “Manville can do the greatest job in the world with its Watershed Improvement Plan, but if they don’t incorporate what is going on upstream, there is no way they will solve flooding,” according to James Cosgrove of One Water Consulting. It is an unfortunate reality that the inaction of upstream communities often sets the stage for water quality impairments that are felt by downstream residents. Absent strong regional cooperation between municipalities throughout the entirety of the North and South Branch Raritan Watershed Management Area to take measures to capture and store excess stormwater, Manville will be on its own.

President Joe Biden tours a neighborhood in Manville Borough and talks with residents affected by the flooding caused by Hurricane Ida

Operating as 564 separate systems is both tedious and redundant when it comes to watershed planning. While some municipalities may not deal with severe flooding as frequently as others, all towns, and the state, benefit from a healthy watershed. Simple river restoration actions, like tree plantings, streambank support, and water quality testing can ensure that freshwater drinking water sources are protected from non-point source pollutants. Low-cost green infrastructure projects capture, store, and filter excess stormwater to prevent it from overwhelming roads and waterways.

The Watershed Improvement Plan (WIP) for each municipality entails three phases: a Watershed Inventory Report, a Watershed Assessment Report, and a final WIP Report. While each municipality must complete its own WIP, there are opportunities for collaboration throughout its multi-year development process. For example, municipalities can work together to complete outfall drainage area mapping, which often spans across local borders and may require assistance from external consultants. Also, holding public information sessions to relay findings from Watershed Assessment Reports would be incredibly more efficient if convened on a regional basis, in contrast to independent meetings with residents. An open dialogue is vital to the watershed improvement planning process. “We want to engage community representatives early in the process. Across the state, advocates are working on these exact kinds of solutions, and they may have the solutions already in play, but simply need to be connected with one another to create effective change,” according to Nicole Miller of MnM Consulting.

Regional collaboration has the capacity to effectively and efficiently improve flooding and water quality, foster relationships between municipalities, save time, and save costs for all parties involved. Local watershed associations are well-poised to facilitate regional conversations, as they are well-established groups that routinely work with municipal officials. Municipalities may lack the tools or expertise for regional watershed-based planning on their own, but as Tom Dallessio of the Musconetcong Watershed Association explains, “Our job as a watershed association is to work with communities to improve water quality… You can’t address issues like water quality without a plan in place.” As municipalities work to draft their Watershed Improvement Plans under the new MS4 Permits, they must pursue every opportunity to work across municipal borders and with local watershed organizations to pool resources and share knowledge to build a more resilient watershed in the face of exacerbated flooding and water quality impairments under climate change.

New Jersey’s Housing Landscape: The Mount Laurel Doctrine and the Search for the Missing Middle

July 30th, 2024 by Tim Evans

The rising costs of housing in New Jersey are affecting everyone, especially individuals and households at the lower end of the income spectrum. New Jersey’s unique Mount Laurel doctrine is meant to address the need for housing for lower-income households, but it also indirectly has a major effect on the supply of market-rate multi-family units in the process. The process by which towns satisfy their affordable housing obligations does not guarantee a full range of housing options for a full range of household types and incomes. The Mount Laurel requirements ought to serve as a prompt for towns to think holistically about their housing supply in general—how much and what types of housing will they need to accommodate the needs of future residents?

Panelists in the session “Knowing the Numbers: Housing Allocation, Patterns of Development and the Future of Housing” at the 2024 Planning and Redevelopment Conference discussed the current state of affairs in housing in New Jersey, for affordable housing and beyond. Moderator Creigh Rahenkamp, Principal of CRA, LLC, and Tim Evans, Research Director at New Jersey Future, gave background about the housing supply in general, and Katherine Payne, Director of Land Use, Fair Share Housing Center; Graham Petto, Principal, Topology; and David Kinsey, Partner, Kinsey & Hand talked about what to expect from the latest changes to the state’s system of incentivizing affordable housing. Panelists all agreed that the Mount Laurel system is necessary but not sufficient to provide the full range of housing options that New Jersey’s future population will need.

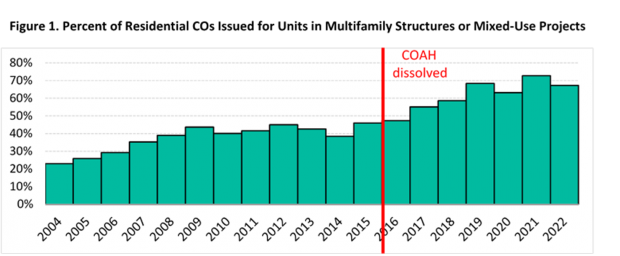

“Mount Laurel” and Affordable Housing

The Mount Laurel doctrine refers to a series of New Jersey Supreme Court decisions that direct municipalities to provide their “fair share” of the regional need for low- and moderate-income housing. For many years, enforcement of the requirements was the responsibility of the Council on Affordable Housing (COAH), but the Council was effectively dissolved in 2015 when the Court deemed it ineffective and handed enforcement authority back to the judicial system. Payne cited her organization’s 2023 report Dismantling Exclusionary Zoning: New Jersey’s Blueprint for Overcoming Segregation to point out that the annual production of affordable units increased substantially after 2015 under the subsequent more rigorous court oversight. (She pointed out that the vast majority of affordable housing is produced in the form of multifamily housing.) The report also found that most of the overall growth in multifamily housing (primarily apartments) over the same time period has been achieved in inclusionary Mount Laurel projects, projects that contain both income-restricted and market-rate units, to the extent that 81% of all multifamily units built since 2015 were built in connection with the Mount Laurel process. Reinforcing this relationship, Evans cited data showing certificates of occupancy (COs) for multifamily housing rising in the post-COAH era (see Figure 1 ) to the point where multifamily units now account for more than half of all housing production. “This shift in permitting activity is being driven by Mount Laurel-associated re-zonings,” Payne said.

Production of multifamily housing has increased steadily in the post-COAH era. More than 4 out of 5 multifamily units built since 2015 are associated with Mount Laurel projects, either as affordable units or as market-rate units that are part of mixed-income projects.

Administration of the Mount Laurel process has recently undergone another significant change with the passage of new legislation, in the form of Assembly Bill 4/Senate Bill 50 this year. Among other things, the legislation sets up an oversight mechanism within the executive branch and directs the Department of Community Affairs to implement a methodology for determining municipal affordable housing obligations, based on three factors—income capacity, non-residential property valuation, and developable land. While the rules will take time to create, Petto said municipalities can and should get started now in preparing plans for compliance, including thinking about where in town the Mount Laurel units will be located and how to earn extra credit for certain types and locations. Kinsey mentioned that the legislation allows for bonus credits for such features as proximity to public transportation, special-needs or supportive housing, and redevelopment of a retail, office, or commercial site.

Redevelopment as the New Paradigm

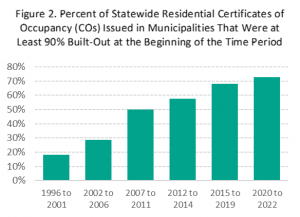

Many new Mount Laurel units will be constructed in redevelopment areas, if the overall pattern of population growth in recent years is any indication. Evans showed that most of the state’s housing growth over the last decade and a half has been happening in already-built-out areas (see Figure 2 ).

Redevelopment is the new normal: An increasing share of New Jersey’s housing growth has been happening in already-built places.

It is clear that “built-out” does not necessarily mean “full,” and that redevelopment areas offer plenty of opportunities for municipalities to create more housing, both for Mount Laurel and market-rate. As such, the new legislation requires municipalities to develop plans for “conversion or redevelopment of unused or underutilized property, including existing structures if necessary, to assure the achievement of the municipality’s fair share” of affordable housing.

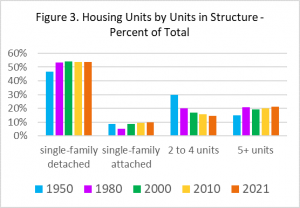

The “Missing Middle” Is Still Missing

Payne reminded listeners that the Mount Laurel doctrine originally arose when the New Jersey Supreme Court ruled that municipalities cannot practice “exclusionary zoning,” by which they effectively exclude lower-income households by writing their zoning codes to allow nothing but single-family detached homes, which are less affordable to households of modest means. Such zoning is still very common: “About 75% of land in major US cities is zoned exclusively for single-family housing, which has implications for access to opportunity,” Payne said.

While the Mount Laurel process was set up to ensure the provision of housing for lower-income households, it does not address other types of housing that are left out by exclusionary zoning and are thus in short supply. The wide array of housing options between single-family detached units on one end of the scale and large apartment buildings on the other are often called the “missing middle,” because many places simply don’t plan for them. This includes options like duplexes, triplexes, small apartment buildings, apartments above stores, and accessory dwelling units (ADUs), a category that itself includes small, separate units that are attached to or on the same property as a larger unit, like above-garage apartments or “in-law suites.” Evans illustrated how housing units in 2-, 3-, and 4-unit buildings have declined as a share of total housing units, from 30% of all units in 1950 to half that share as of 2021 (see Figure 3 ). Kinsey further noted that the number of units in structures with 2 to 4 units has actually decreased in absolute terms, dropping from about 514,000 in 1970 to about 490,000 in 2020.

“Missing middle” housing options in buildings with 2 to 4 units have declined dramatically since 1950 as a share of total housing units.

Another conference session, “We’re Missing Middle Housing in New Jersey: How to Fix It,” was devoted entirely to these missing options and strategies to bring them back. One of the speakers in that session, Karla Georges of the national American Planning Association, identified states where “missing middle” housing bills have passed, including Washington, Colorado (HB1316 and HB1175, and Arizona. Kinsey mentioned one modest New Jersey effort, bill S2347 currently being considered by the legislature, that would authorize ADUs statewide. Meanwhile, some New Jersey municipalities have legalized ADUs on their own, without waiting for statewide legislation.

In any event, while New Jersey is ahead of most of the rest of the country in having the Mount Laurel doctrine and its supporting legislation, this is insufficient as a mechanism for ensuring the production of a full range of housing types, without which people will continue to migrate out of New Jersey in search of cheaper options. As New Urbanist pioneer Peter Calthorpe has observed at the national level, “We cannot build this country on subsidized housing. We’re never going to get the end result. We have to create the context, the policies, and the zoning that make middle housing viable and located in the right locations.” New Jersey now needs to follow the lead of other states in exploring strategies to break the stranglehold of single-family zoning, so that households of all incomes can afford to call New Jersey home.

Municipal Leaders Claim Public Engagement is Largest Asset to Lead Replacement Efforts

June 24th, 2024 by New Jersey Future staff

By Andrea Jovie Sapal and Deandrah Cameron

“We collectively work towards a future where every resident in New Jersey has access to clean, safe, and lead-free drinking water by fostering collaboration and sharing knowledge through innovation,” declared Richard Calbi, Director of Ridgewood Water, as he opened the lead service line replacement session at the 2024 Planning and Redevelopment Conference. This session focused on a critical environmental justice issue that demands our urgent attention—the presence of lead in drinking water in New Jersey.

Lead service lines (LSLs) account for 75% of all lead in drinking water exposure and are particularly harmful to formula-fed infants and children under six. New Jersey leads the way in LSL replacement with one of the strongest mandates across the country. In 2023 NJ was designated by the Biden Administration as one of four states participating in the US Environmental Protection Agency’s LSL Replacement Accelerator program, in part for NJ’s aggressive approach to service line replacement and emphasis on planning and municipal coordination. Last month, the EPA announced that NJ will receive $123 million in federal funding from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law through the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund. The cost estimate for LSL replacement in NJ is roughly $3 billion.

Although funding is a major issue, engaging customers proves to be the most difficult hurdle. Moderator Richard Calbi stated, “The bulk of the financial burden will fall on water systems, resulting in increased water rates for consumers.” Consumers, i.e. regular households and businesses that pay for water, are the biggest stakeholders and face the burden of paying for their lead lines as water systems design replacement programs. While some programs offer free replacement, most systems will charge a cost. According to one report, a single LSL replacement could cost on average $6000 with high costs over $9,000—accounting for the cost of living differences, unique building or pavement materials, paving requirements, and unique permit fees. Speakers Kouao-eric Ekoue, Superintendent, City of New Brunswick Water Utility; Noemi de la Puente, Principal Engineer, Trenton Water Works; and Stephen Marks, Town Administrator, Town of Kearny shared their expertise on the state and federal partnerships, cost reduction strategies, and community engagement at the “Leading the Way: Cost-Saving Solutions for Coordinating Lead Service Line Replacement with Municipal Projects and Processes” session.

Featured speakers Kouao-eric Ekoue of New Brunswick Water Utility and Noemi de la Puente of Trenton Water Works (TWW) represent two of NJ’s accelerator cities (more below). State support for local assistance is critical for advancing LSL replacement projects. In conjunction with the federal LSL Replacement Accelerator program, the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) launched NJ-TAP, an initiative providing enhanced technical assistance for disadvantaged communities to provide safe and reliable drinking water to residents. New Brunswick Water Utility leverages both federal and state programs to assist in changing ordinances, accessing funds through the SRF program and bonds, integrating data validation tools, and self-testing and electronic identification surveys as part of community outreach. On the topic of effective strategies to gain community support, Ekoue stated that his administration is fully involved in the process, emphasizing the importance of municipal engagement early on since without that buy-in, the projects are not going to go anywhere fast.

New Jersey’s ten federal LSL Replacement Accelerator cities include:

- Blackwood

- Camden

- Clementon

- East Newark

- Harrison

- Keansburg

- Keyport

- New Brunswick

- Trenton

- Ventnor City

LSL replacement can be challenging for water systems that serve multiple municipalities where program planning looks different for each locality. This type of coordination and cross-collaboration requires ingenuity; moderator Rich Calbi noted, ”We must explore innovative strategies and best practices to help municipalities navigate these challenges effectively and alleviate the burdens placed on residents as we work toward compliance with this vital mandate”. The City of Trenton serves five municipalities: Trenton, Ewing, Hamilton, Lawrence, and Hopewell, each requiring a unique approach.

Trenton Water Works’ engineer Noemi de la Puente discussed challenges and potential solutions around the Three Ps: Paving, Policing, and Permitting. Each municipality has different paving jurisdictions, and without coordination, replacements could be unnecessarily costly. In 2022, when de la Puente inherited the program from her predecessor, she asked, “How are we going to reshape the TWW LSL replacement program overall at a rate that isn’t expensive?”. Some potential cost-saving solutions de la Puente is looking to explore include streamlining the hyperlocal permitting process by coordinating LSL replacement plans with paving projects associated with sewer maintenance plans, main replacements, and other paving projects across jurisdictions. Since funding is a challenge, de la Puenta emphasizes that partnering with these projects would allow the leverage of Clean Water State Revolving and Drinking Water State Revolving Funds as well as funds allocated through the NJ-Moves program for paving projects. To date, de la Puente mentions needing a total of 961 permits totaling $111,476, concluding that these fees could be significantly lower with coordinating across programs.

De la Puente stressed that the strongest collaboration TWW can form is with their customers because they require access to 62,000 basements to identify lead service lines. The faster they can identify the inventory, the quicker they can complete the project. “If I [knew] my entire inventory next week, the rest of my lead service line replacement project will go much more smoothly,” concluded de la Puente.

If I [knew] my entire inventory next week, the rest of my lead service line replacement project will go much more smoothly.

—Noemi de la Puente of Trenton Water Works

The Town of Kearny also utilized an ordinance to develop a free and mandatory program coupled with a cost reduction that includes combining the town’s resurfacing program with its LSL replacement program. However, Marks expressed that it won’t happen all at once “Given the density of digging test pits every 25 to 40 or 50 feet, it made the most sense for the town of Kearny to incorporate the lead service line replacement into the road resurfacing program. The town has a moratorium on digging up any streets that have been paved within the last five years, so we’re actually focused on all the streets that haven’t been paved on the outer end of 10 to 15 years or more.” This means depending on when the road was last paved, customers may have to wait years before the replacements are scheduled to begin. To mitigate this, the Mayor and Council also passed supplementary ordinances to reimburse all customers who coordinate their own replacement should they decide to move ahead of the town’s schedule.

“100% of the census tract for the Town of Kearny is considered overburdened by the state of New Jersey,” and about half (46%) of the town is considered low-moderate income

—Stephen Marks, Town of Kearny

Overburdened communities often struggle to pay cost shares. Town of Kearny Administrator Stephen Marks highlighted that “100% of the census tract for the Town of Kearny is considered overburdened by the state of New Jersey,” and about half (46%) of the town is considered low-moderate income. The Town of Kearny also utilized funding through the Federal Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) as an alternative source of funding through which a portion of the town became eligible based on census tract and income level. Marks explained that funding is a constant challenge and that municipalities are constantly deciding between the lengthy SRF process that may offer the potential for principal forgiveness or choosing to engage in the private market which could be more costly but quicker. In response to the notice of the $123 million in federal funding, Marks stated that municipalities have a decision to make as regards timeliness and meeting the 2031 goal. For example, he explained that an $8 million project is a trade-off between a “six-month” I-Bank application process with the hope of possible principal forgiveness compared to self-financing through the private market where there is no principal forgiveness but saves time. In addition to funding and coordination Marks also shared similar challenges to his fellow panelists around property access, expressing that residents typically do not want the town accessing basements or private spaces especially where they potentially have an unpermitted conversion of the basements.

The overlapping theme among the municipal leaders was that community engagement is extremely important, especially in overburdened communities where customers face a number of challenges, including cost sharing for LSL replacement. Partnerships with community groups and local leaders play a pivotal role in the successful replacement of LSLs and facilitating coordination between different jurisdictions and projects. The ultimate objective of achieving lead-free drinking water necessitates a multi sector approach that offers cost-effective solutions. Cooperation among various local, regional, and state leaders is crucial for effective implementation. The Primer for Mayors outlines ten efficient measures for LSL replacement and guides municipal officials on how to initiate this process in their community. This Jersey Water Works resource is a prime example of an initiative that supports all municipalities by providing the necessary tools and strategies for effectively replacing lead service lines. By July 10, 2024, water systems must submit their updated annual inventories and LSL progress reports. This increased transparency and communication are crucial steps towards addressing the ongoing issue of lead in drinking water.

To learn more about Jersey Water Works and the Lead in Drinking Water Taskforce, join us at the July 17th membership meeting in person. Registration is free, attendees do not need to be a member of the collaborative to attend. Register today! For more information contact Jersey Water Works (info jerseywaterworks

jerseywaterworks org) .

org) .

Unlocking Opportunities: Securing Funding for Trail-Related Projects

June 24th, 2024 by Zeke Weston

As the nation’s most densely populated state, New Jersey packs in more people per square mile than anywhere else. Our most vibrant cities and towns include compact, walkable downtowns and active streetscapes—complemented by accessible greenways and trails for recreation, a respite from urban life, and healthy, carbon-free travel. But being the Garden State, we can do so much more.

New Jerseyans enthusiastically support and want more greenways and trails. The public input process for the new draft Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (SCORP) included over 15,000 survey responses that identified hiking, walking, and gathering as top priorities, with trails highlighted as one of the most important outdoor amenities. Nonetheless, residents from the SCORP’s public focus groups mentioned several barriers to full participation in outdoor recreation, notably limited transportation options, whereby participants can comfortably travel to outdoor spaces. To overcome these barriers, towns and counties need to comprehensively plan and design trail projects that are safe, accessible, and well-connected. Most communities want to build outdoor recreation and active transportation facilities but lack the funding and resources to make them a reality.

Most communities want to build outdoor recreation and active transportation facilities but lack the funding and resources to make them a reality.

A panel titled “Connecting Communities to Capital for Greenways, Trails, and Bike Paths” addressed these issues and priorities at the 2024 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference (NJPRC), sponsored by New Jersey Future and the New Jersey chapter of the American Planning Association. Panelists brought a broad range of experiences to the discussion and an even greater depth of on-the-ground experience. They included: moderator Olivia Glenn, Chief of Staff and Senior Advisor for Equity, US EPA Region 2; Byron Nicholas, Chief, Division of Planning, Hudson County; Elizabeth Dragon, Assistant Commissioner, Community Investment and Economic Revitalization, NJ Department of Environmental Protection; Laine Rankin, Assistant Commissioner, Local Resources and Community Development, NJ Department of Transportation; and Teri Jover, Borough Administrator and Economic Development Director, Borough of Highland Park.

In her opening remarks, Olivia Glenn emphasized the importance of federal funding for state and local governments to invest in active transportation infrastructure, especially from the Inflation Reduction Act. She highlighted the $4 million awarded to New Jersey’s local, county, and state governments from the EPA’s Government to Government program last year. The funds will be used for government activities in partnership with Community-Based Organizations that result in measurable environmental and public health improvements in overburdened communities. One of the many types of projects the program can fund is urban greenways. Urban greenways provide access to nature and clean transportation corridors while simultaneously reducing the urban heat island effect. Because of their multifaceted benefits, Glenn emphasized the ability for trail-related projects, like urban greenways, to be funded by a wide variety of grant programs, not just transportation ones.

Teri Jover provided insight into how these types of projects come to fruition at the local level in a municipality. The Highland Park River Greenway was a dream of the Borough’s residents and elected officials for decades. In 2017, the Borough finally developed a one-page description of the Greenway to share with the county and state. At that time, Jover noted that the project needed to be fleshed out in more detail for it to advance. Because of Highland Park’s limited staff capacity and resources, she highlighted the Borough’s inability to afford a consultant despite needing one. Fortunately, Highland Park applied for and received a budgetary grant from the NJ Department of Community Affairs to conduct the feasibility studies and topographic surveys needed for the project, which was funded by a one-time earmark from the state legislature. This grant allowed the Borough to conduct the analysis and planning to push the project forward, but Jover acknowledged the need for additional money to construct and then maintain the Greenway. This will be a long-term project, as many greenways are, and, she emphasized the importance of staying committed to these projects until the end.

Byron Nicholas spoke to the regional perspective and process for advancing trail projects, drawing on his experience with various Greenways in Hudson County. Because Hudson County is the most densely populated county in the state, access to riverfronts and open spaces is limited despite the existence of the Hudson, Hackensack, and Passaic Rivers. Therefore, the county looked at how to improve access to outdoor amenities while providing alternate transportation options. This resulted in the 2022 Hackensack River Greenway plan. The County needed to develop a concept design for the Lincoln Park segment of the Hackensack River Greenway, so they applied for and received a grant of approximately $1.5 million from the Transportation Alternative Program (TAP). The TAP grant funded the preliminary and final designs of the Greenway and the beginning of construction. From this experience, Nicholas emphasized the importance of establishing and maintaining relationships with your project partners. He noted that their bi-monthly working group meetings were critical to the project’s success and should be a component of all regional trail projects.

Hackensack River Greenway

Elizabeth Dragon emphasized the importance of intentional planning for successful trail projects. Effective trail planning includes research, community engagement, and alignment with state and local initiatives. When reviewing grant applications to the Green Acres Program, Dragon noted that the most competitive applications identify the project’s economic, environmental, and community benefits and demonstrate its positive impact on local business, tourism, environmental preservation, and social cohesion. She highlighted the importance of addressing the NJ Department of Environmental Protection’s triple bottom line in the grant application: economy, environment, and people. Connecting your trail or greenway project to these priorities and outcomes cannot be overstated. Similarly, Dragon noted the need to identify how the project complements local and state land use plans. The most successful applications are consistent with these plans and their priorities.

The most competitive grant applications highlight the project’s economic, environmental, and community benefits and identify its positive impact on local business, tourism, environmental preservation, and social cohesion.

Laine Rankin described the funding opportunities available at the NJ Department of Transportation for trail-related projects. She identified the state’s Bikeways Program and Municipal Aid Program as opportunities for towns and counties to access funding for such projects. Rankin made sure to note that the state’s programs are intended for shovel-ready projects that have already completed the planning and design phases. For example, Montgomery Township received a $360,000 Municipal Aid grant in 2020 to build 1.5 miles of bike lanes and 2.1 miles of new multi-use paths around Skillman Park. On the other hand, Federal programs for trail-related projects, like the Transportation Alternative Set-Aside (TASA), do not have the same shovel-ready requirements. For instance, Burlington County received a $440,000 TASA grant in 2020 to build a portion of the Delaware River Heritage Trail along the Route 130 bypass. Rankin reiterated the importance of knowing what project types each program funds so that towns apply to the most appropriate program for their needs.

Now, more than ever, New Jersey needs to meet its residents’ wants and needs for greenways and trails that provide equitable mobility and access to nature. The state’s municipalities and counties can make this a reality, but they need to know the appropriate funding programs to do so. Towns interested in trail-related projects should contact their County planning departments and Metropolitan Planning Organizations for further assistance and information.

NJDOT’s Safe Streets to Transit Program Is Improving Communities Across the State – Yours Can Be Next

March 19th, 2024 by Zeke Weston

Simple, small-scale transportation features make a community a safer, healthier, and more affordable place to get around. In a community that values street safety, crosswalks are clearly marked and strategically placed to ensure easy and safe passage for pedestrians. Streets are lined with wide sidewalks, benches, and trees to encourage walking. Dedicated and protected bike lanes provide safe access for cyclists and scooter riders. In safe streets communities, commuters seamlessly walk to the bus stop or train station to get to work, children safely ride their bikes to school, and people of all ages and abilities confidently enjoy a stroll to the park. Through the New Jersey Department of Transportation’s (NJDOT) Safe Streets to Transit (SSTT) program, this type of community can become a reality.

The SSTT program funds municipalities and counties to improve safety and accessibility for public transit riders walking to transit facilities. To do so, NJDOT awards municipal and county grants based on the following criteria:

- Proximity to public transit facilities

- Improved safety

- Increased accessibility

- Access to schools

- Pedestrian incidents

- Complete streets

This year’s 22 grants represent the largest amount of funds provided in a single year by the SSTT program, $13,629,000. They will fund projects in communities ranging from towns to suburbs to cities. It’s imperative that municipalities have the proper funding to realize even simple infrastructure improvements. Every piece counts as we weave a statewide network of multimodal transportation infrastructure. With NJDOT’s next round of funding opening up in April 2024, this is a good opportunity to review examples of successfully funded projects across the state.

Longport Borough, located on Absecon Island in Atlantic County with a population of around 8001, received an SSTT grant of $1,000,000. The Longport project will make traffic-claiming improvements on Amherst, Sunset, and Winshecter avenues in the East Bayfront neighborhood. These three streets feed onto the JFK Memorial Bridge; therefore, the East Bayfront experiences high levels of fast-moving traffic2. By implementing traffic calming measures like raised sidewalks and speed tables, Longport will make the neighborhood safer for pedestrian and bicycle traffic. This will better enable East Bayfront residents to safely walk or bike to and from the NJ Transit bus stops along Ventnor Avenue in the center of Longport.

North Bergen Township, located across the river from Manhattan in northern Hudson County with a population of around 62,000, also received an SSTT grant totaling $948,000. The North Bergen project will implement safety upgrades for sidewalks and crosswalks near bus and rail stations along Bergenline Avenue from 70th Street through James J. Braddock North Hudson Park3. Bergenline Avenue is home to numerous NJ Transit bus stops; thus, the safety improvements are designed to promote the use of public transit and encourage riders to walk to their bus stops.

The Town of Princeton in Mercer County was awarded $1,000,000 to improve pedestrian access and safety between two NJ Transit bus stops and new housing developments. With this grant, Princeton will reduce reliance on car-travel by promoting the use of public transportation through pedestrian infrastructure improvements. Princeton’s SSTT grant will enhance pedestrian safety on Terhune Road and North Harrison Street. Specifically, the project will finish the construction of an existing sidewalk network in this corridor and add new sidewalks and traffic calming measures that will make Terhune Road safer for pedestrians and bicyclists. This initiative will provide safe and equitable access to the bus stop on Terhune Road and the bus stop in the Princeton Shopping Center off North Harrison Street.

Princeton residents walking and biking to and from the NJ Transit bus stop.

Although the project’s active transportation infrastructure improvements are noteworthy, it’s not the only reason to highlight its importance. Princeton is combining the SSTT project’s safety improvements with developer-funded bicycle and pedestrian improvements between North Harrison Street and Grover Avenue. These enhancements will include new sidewalks, raised crosswalks, and a bike lane on the south side of Terhune Road. The municipality will complement the developer-funded improvements by replacing the sidewalks between North Harrison and Thanet Circle, raising an intersection, and creating a bike lane on the north side of Terhune Road. This collaboration demonstrates the potential that public-private partnerships have for making the most out of every grant opportunity for the better of the community.

The Princeton Shopping Center with the new housing development in the background.

The new nearby housing developments include affordable homes for people of low- and moderate incomes. The pedestrian improvements from the SSTT grant will help connect affordable housing to public transportation opportunities. Residents of the new housing will be able to walk to multiple NJ Transit bus stops and the shops in the Princeton Shopping Center.

New housing development near the Princeton Shopping Center.

From Princeton to Longport to North Bergen, all types of communities, big or small, urban or suburban, can benefit from NJDOT’s SSTT program, and your community can be next. NJDOT will open a new round for the SSTT in April, and applications will be accepted until July. If you are an individual who cares about street safety, now is the time to inform your municipal leaders to begin preparing an application. New Jersey Future encourages municipalities large and small to seize this opportunity and apply to NJDOT’s SSTT program when it opens in April.

1 https://censusreporter.org/profiles/16000US3441370-longport-nj/

Transit-Oriented Development Is Popular, but Won’t Happen by Itself

March 15th, 2024 by Tim Evans

Westfield Northside Town Square rendering from the Lord & Taylor / Train Station Redevelopment Plan which was a 2023 Smart Growth Award recipient.

New Jersey’s transit towns are experiencing something of a revival in the last decade and a half. This is an important positive development, since transit-oriented development (TOD) advances multiple societal goals. For example, TOD is an effective strategy to reduce the state’s greenhouse gas emissions, both by encouraging transit ridership (which is much more efficient on a per-traveler basis than travel by personal vehicle), and because TOD’s compact development form brings destinations closer together, shortening vehicle trips and enabling more trips to be taken without need for a car altogether. TOD’s natural focus on pedestrian accessibility, dating to an era when most transit riders arrived at the station on foot, encourages improved pedestrian and bicyclist safety. And many (though certainly not all) transit neighborhoods feature a diverse mix of housing types—single-family detached homes, but also townhouses, duplexes, apartments above stores, small apartment buildings—that enable households of many types and income levels to take advantage of the benefits of living in a place where not every trip requires a car.

New Jersey hosts nearly 2501 transit stations, spread among 153 municipalities that host at least one of them, with many towns in the transit-rich urban core of North Jersey hosting multiple stations. The state’s transit nodes include ferry terminals; major bus terminals; stations on the PATH and PATCO rapid-transit systems, which connect New Jersey with New York and Philadelphia, respectively; and a host of New Jersey Transit commuter-rail and light-rail stations. Having invested in and constructed one of the most extensive public transit networks in the country over time, New Jersey is now blessed with plenty of opportunities to facilitate TOD.

A rendering of the South Orange Taylor Vose building and 2022 Smart Growth Award recipient. The building combines transit-oriented development, affordable housing, community usage, and local business.

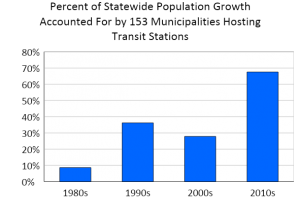

TOD is currently popular in New Jersey. The 153 transit-hosting municipalities grew twice as fast as the rest of the state between 2010 and 2020.

Facilitating more TOD would be a popular move among potential residents, if recent trends are any indication. The 153 transit-hosting municipalities grew twice as fast as the rest of the state between 2010 and 2020—the combined population of the transit municipalities increased by 7.7%, vs 3.4% growth for the balance of the state. Together, the transit municipalities accounted for more than two-thirds (67.6%) of total statewide population growth between 2010 and 2020, up substantially from the three previous decades, when jobs were clustering in suburban, car-dependent office parks, and when low-density residential subdivisions were the dominant form of new housing. Transit municipalities have transitioned from representing a disproportionately low share of total population growth in the prior three decades (they make up about half of total statewide population but were accounting for a much smaller share of new population growth) to now contributing a disproportionate majority of total growth.

Given the popularity of transit-oriented development, and its potential to attract and retain young adults who might otherwise leave the state, we should create more of it.

The resurgence of transit towns is one aspect of the recent shift in demand, particularly among young adults, toward compact, mixed-use, walkable places that offer a live-work-play-shop environment where not every trip requires a car. Transit-oriented development is by nature also pedestrian-oriented development, since transit riders become pedestrians the moment they step off the bus, train, or ferry. With transit stations historically serving as focal points for many of New Jersey’s cities and first-generation suburbs, important destinations clustered within easy walking distance of the station, capturing foot traffic among commuters en route to and from the station but also making non-work trips shorter and more efficient, often without needing a car, for all local residents, whether or not they were transit commuters. Transit towns are once again attractive to a new generation of residents who don’t want to drive everywhere, even if they are not regular transit riders.

Given the popularity of transit-oriented development (TOD), and particularly its potential to attract and retain young adults who might otherwise leave the state seeking similar but cheaper living environments elsewhere, New Jersey should be looking for ways to create more of it.

Obstacles to TOD

Many transit towns have historically embraced density, with many residential and commercial destinations all located in close proximity to the transit station and to each other, allowing many trips to be taken by transit or by non-motorized means. But others more closely resemble their car-dependent suburban neighbors in terms of the variety of housing options they offer. Among the 153 transit towns are 63 municipalities in which two-thirds of the housing stock consists of single-family detached units, compared to a statewide percentage of 53.1%; in 35 of the 153, single-family detached homes comprise 75% or more of all housing stock.

In some places, local zoning does not permit the density and diversity of housing types that TOD relies on to succeed, denying needed housing options to many households in the process. A new report from the Regional Plan Association, Homes on Track: Building Thriving Communities Around Transit, finds a whole host of commuter rail stations throughout the New York metropolitan region, including in New Jersey, that require “extensive zoning changes to allow multi-family and mixed-use at appropriate densities” in order to reach their full TOD potential. To unlock that potential, the state should consider enacting zoning reforms, as Oregon, California, Montana, and numerous individual cities around the country have done to varying degrees. Among the reform techniques are TOD overlay zones that specifically allow as-of-right creation of certain alternatives to single-family housing in transit-adjacent neighborhoods, alternatives that will both boost access to transit for a greater number and variety of households, and encourage greater return on state investments in transit by growing ridership. As a further incentive for municipalities to revisit their zoning codes to allow for greater housing variety, some of these other housing options could be used to satisfy affordable housing obligations under the Mount Laurel process, which are due to be updated and are currently the subject of legislative proposals.

Minimum parking requirements are another regulation that inhibits the development of housing near transit (and everywhere, for that matter), preventing transit-rich towns from meeting demand and undermining the general principles of TOD. Parking requirements force developers to devote land to vehicle storage that might otherwise be used for more housing units, retail options, public spaces, or other more productive uses. They reduce the affordability of the units that get built by forcing developers to spend money on parking, increasing the per-unit costs. Parking lots also force buildings farther apart, undermining the benefits of density that allow people to walk safely from one destination to another and increasing the likelihood that they will drive instead, an ironic effect in neighborhoods where transit offers an alternative to driving.

Even for towns that want to promote TOD and transit ridership, transit funding is a source of uncertainty. NJ Transit does not have a dedicated source of funding, relying instead on the vagaries of the annual budget process, and on periodic (and unpopular) fare hikes. Without stable and reliable funding, transit-hosting municipalities may be reluctant to engage in planning and development focused on state-owned facilities whose long-term viability is not guaranteed. Promoting TOD without a guarantee that the state will continue to adequately fund transit service amounts to false advertising.

The town plaza in pedestrian-friendly downtown Metuchen, a notable Transit Village. Metuchen received a Smart Growth Award in 2017 for its Woodmont Metro at Metuchen Station, a project designed to help implement its Town Center Design and Development plan.

Making TOD Happen

On the positive side, state agencies offer some valuable programs and resources for transit-hosting towns that want to encourage TOD and pedestrian-friendly street networks in the adjacent neighborhoods, including:

- The Transit Village Initiative, jointly operated by NJDOT and NJ Transit, which offers planning assistance to municipalities with transit stations that want to pursue TOD.

- NJ Transit’s Transit Friendly Planning Guide, which contains guidelines and design principles for making a place more transit-friendly, with strategies and techniques tailored to the type of development that already surrounds the transit station; recommendations address both transportation/access and land-use characteristics.

- NJDOT’s Complete Streets Design Guide, which provides a host of street design techniques for making streets more friendly to pedestrians and other non-motorized travelers, a goal that is particularly relevant in transit-focused communities

NJ Transit is also drafting a TOD policy to inform land-use decisions on and near property that it owns. New Jersey Future’s comments on the draft policy can be viewed here.

State and local governments need to address the policy and regulatory factors that stand in the way of providing TOD to present and future residents.

Our comments on NJ Transit’s TOD policy echo recommendations from our 2012 report Targeting Transit: Assessing Development Opportunities Around New Jersey’s Transit Stations. Most of the recommendations aimed at promoting more transit-friendly development are still relevant today, including:

- Expand and improve the public transit system with sustainable funding. (Recent discussions about how to fund NJ Transit demonstrate that this remains an unresolved issue.)

- Foster transit-oriented development projects on NJ Transit-owned sites. (NJ Transit’s TOD policy is an important step in this direction.)

- Strengthen state programs that foster TOD. (This could include greater support from the Transit Village program for municipalities that agree to increase zoning density near stations.)

- Facilitate structured parking. (This would mitigate the effect of surface parking lots pushing destinations farther apart and discouraging walking.)

- Enlist municipal support for zoning changes. (Given recent interest, and even some successes, in other states, state-level zoning reforms should be pursued too.)

- Foster good design to ensure attractive, pedestrian-friendly station areas. (This may entail a comprehensive review of all the disparate factors that affect how local streets get designed.)

- Promote a range of housing options near transit.

As a transit-rich state, New Jersey is not lacking in TOD potential. Recent population growth trends indicate there is demand for more such development. State and local governments need to address the policy and regulatory factors that stand in the way of providing TOD to present and future residents.

1 The exact number depends on how you count. For example, should the Glen Rock stations on the Main and Bergen commuter rail lines count as one station or two? Or the Exchange Place stations on PATH and Hudson Bergen Light Rail, and the ferry terminal of the same name? See New Jersey Future’s 2012 report Targeting Transit: Assessing Development Opportunities Around New Jersey’s Transit Stations for a thorough description of the state’s transit systems and stations.

New Report Digs Deeper into Diversity in Morris and Monmouth Counties

January 29th, 2024 by Tim Evans

New Jersey is an expensive state, with among the highest housing costs in the country. It is also one of the most segregated states in the nation by both income and race, despite being one of the most racially diverse states overall. A new report from New Jersey Future explores the relationship between the enforcement of housing requirements, housing affordability, and racial and economic diversity, using a comparison between two demographically similar suburban counties—Morris and Monmouth—that followed different trajectories in complying with New Jersey’s affordable housing obligations. The findings of our analysis are included in “Breaking Barriers: A Comparative Analysis of Affordable Housing Compliance and Diversity in Morris and Monmouth Counties, New Jersey.”

Morris County municipalities had a head start in meeting affordable housing obligations. Our new report compares their progress to their counterparts in Monmouth County to chart New Jersey’s progress in promoting integration through affordable housing.

The New Jersey Supreme Court’s Mount Laurel decisions in the 1970s and 80s took on the issue of racial segregation by addressing the lack of housing options, eventually leading to a legal requirement for every municipality in the state to provide its fair share of the regional housing need for low- and moderate-income households. But the bureaucratic process set up in the wake of the court decisions, overseen by the Council on Affordable Housing (COAH), featured numerous loopholes via which municipalities could shirk their responsibilities to produce actual housing units. Monmouth County’s municipalities have been governed entirely by the Mount Laurel process, while a group of Morris County municipalities were the subject of a separate lawsuit, initiated in 1978, that predated the second Mount Laurel decision, giving Morris County a head start in compliance with affordable housing obligations.

Housing costs and racial segregation go hand in hand. Many towns use their zoning power to limit the variety of housing options available, allowing primarily single-family detached homes on large lots. The resulting lack of lower-cost housing options renders many places off-limits to households of modest means, particularly Black and Hispanic households, whose incomes tend to be much lower than those for other racial subgroups. Whether motivated solely by fiscal concerns or by race- and class-based prejudices, large-lot zoning often results in segregation by both income and race.

The report considers whether Morris County’s having been the subject of an earlier, separate lawsuit appears to have resulted in the county producing more affordable housing, or achieving greater reductions in racial and economic segregation, compared to Monmouth County. Analysis suggests that the lawsuit was effective; the municipalities of Morris County have outperformed those of Monmouth County in the subsequent decades, in terms of producing new affordable housing. Morris County’s increase in affordable housing was more broad-based than in Monmouth County, happening across all municipalities and not just mainly in the handful of places that had already been providing a disproportionate share of the county’s supply before the COAH process was instituted.

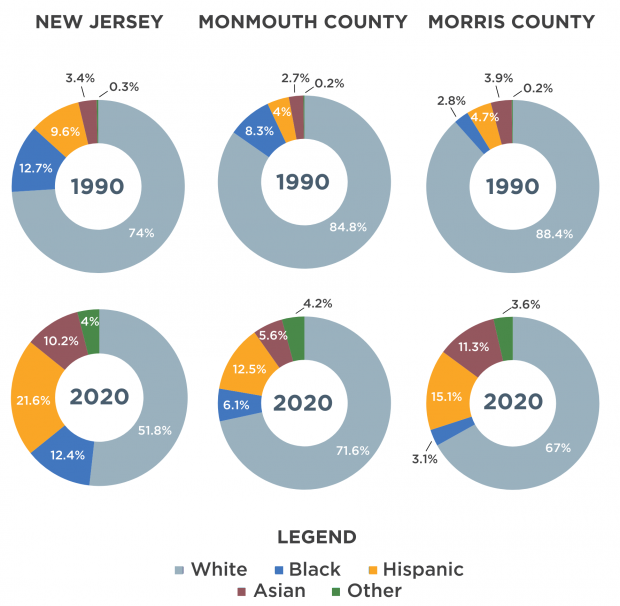

While both counties today remain whiter and wealthier than the state as a whole, Morris County increased in racial diversity and narrowed its gap with the statewide racial distribution at a faster rate than Monmouth County did between 1990 and 2020. This is particularly true with the counties’ Black populations; the Black population share increased in Morris County as a whole and in a majority of its individual municipalities (30 out of 39), while in Monmouth, the Black percentage dropped countywide and in 30 out of 53 municipalities.

While Morris County and Monmouth County both remain whiter than the state overall, Morris has closed its diversity gap with the state faster than Monmouth has.

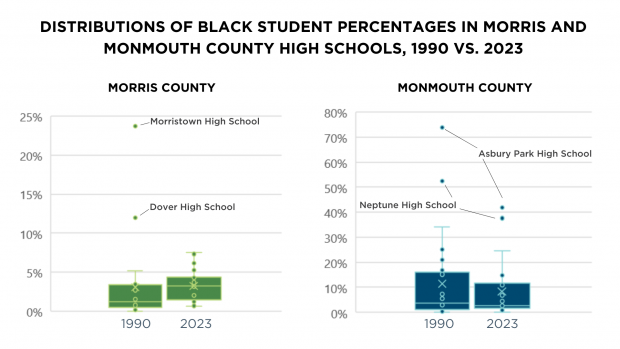

Morris County’s better progress toward reducing racial segregation at the local level is visible in the demographics of the two counties’ high schools, where changes in the Black and Hispanic student populations tended to mirror changes in the demographics of the general population. Morris County high schools generally saw their Black student percentages increase slightly, whereas in Monmouth County, more than half of high schools saw their Black student percentages decline. Hispanic student populations grew across the board in both counties, with the median Hispanic percentage being almost identical in the two counties’ high schools in 2023, though Morris County started from a lower baseline, in relative terms, in 1990. Progress was much less pronounced in both counties regarding income diversity, however, suggesting that the Mount Laurel process alone is simply insufficient to address the housing needs of households throughout the lower and middle parts of the income distribution.

Morris County high schools generally saw their Black student percentages increase slightly, whereas in Monmouth County, the median Black student percentage among the county’s high schools actually declined.

The data examined in this report suggest that targeted enforcement of municipal requirements to produce more affordable housing actually results in more affordable housing. When presented with loopholes like those embedded in the COAH process that allow participants to evade their responsibility to provide housing options for lower-income households, many municipalities will avail themselves of the opportunity. But under more specific accountability, as illustrated by the Morris County lawsuit, towns can indeed be induced to produce a greater variety of housing options, thereby making themselves more affordable to a broader range of households and helping dismantle racial and economic barriers.

The report makes several recommendations for advancing the creation of more affordable housing, and more generally for mitigating local resistance to creating a greater diversity of housing types. Two of the recommendations are of particular interest in light of new legislation being proposed to revise or refine the Mount Laurel process:

- Retain effective enforcement of Mount Laurel obligations: Given the effectiveness of enforcement demonstrated by the report’s findings, it is important that any new legislation retains mechanisms for ensuring municipal compliance.

- Measure progress on affordable housing production and integration: The draft bill encourages greater transparency in how municipal affordable housing obligations are determined and how compliance is measured. Making data consistently available, both on affordable housing production and on some of the metrics of inequity that the Mount Laurel doctrine was designed to address, would advance this goal.

The report’s findings also suggest the need for a broader housing policy agenda to address affordability up and down the income spectrum. While the Mount Laurel process is a critical tool for providing homes for those most in need, the state should not rely on it exclusively as the means of making sure New Jersey remains affordable to a full range of households.