New Jersey Future Blog

Looking to New Jersey’s Future

April 9th, 2020 by Peter Kasabach

Creating strong, healthy, resilient communities

Dear Friends,

As we continue to face crisis and uncertainty during the COVID-19 pandemic, we can draw strength and knowledge from its emerging lessons.

For one, we are learning just how important and central “places” are to our lives. It might be the woods or neighborhood park where we go to escape alone for a few minutes or the bike path where we exercise with our family. It might be our child’s beloved community playground, our downtown square, or our favorite boardwalk along the beach that are currently off limits. It might be the street that we walk our dog down, wave to neighbors from, or hustle along to pick up essential goods. For many of us, it is the homes that we live in and the rooms that we have had to rethink and rearrange, which now double as our schools, offices, and play spaces.

We shape our places today and then they shape us forever. Every day we are revisiting our relationship with the spaces and places we have grown accustomed to and that have made us who we are—home, work, neighborhood, places to play and to be entertained. What made these places work for us before and how will our relationship to them change in a post COVID-19 world? How can we use the lessons learned and the new perspectives gained? How can we emerge stronger and more just?

In the coming weeks, we will be sharing with you the lessons that we are learning on how we can move from crisis to recovery while making New Jersey an even better place. And we look forward to working with you to turn those lessons into powerful new policies and practice that will make New Jersey stronger.

New Jersey Future has a history of helping communities emerge stronger from crises. We were there after Superstorm Sandy, taking the lead at every level of government in helping communities rebuild and become more resilient. We were there to address the recent crisis of lead in New Jersey drinking water, making our state’s communities healthier and safer. And we will be there during the COVID-19 recovery, leading efforts to create strong, healthy, resilient communities for everyone.

In strength and community,

Peter Kasabach

Executive Director

P.S. It’s more important than ever to stay connected. We’ll be updating njfuture.org regularly with important information and resources. Make sure you’re getting our newsletters and following us on social media. Please encourage others to do so as well. Above all, stay healthy and safe.

New Jersey Future and NJDEP release report of local options and actions for resilience

March 13th, 2020 by Missy Rebovich

New Jersey’s coastal communities are already experiencing the impacts of rising seas, erosion, and coastal storms, including property damage, loss of property value, and declines in municipal tax revenues. These 239 coastal communities are home to over 4.6 million people, which represents more than 52 percent of the state’s total population. Action is needed to protect these towns and the people who call them home. But what kind of action?

New Jersey’s coastal communities are already experiencing the impacts of rising seas, erosion, and coastal storms, including property damage, loss of property value, and declines in municipal tax revenues. These 239 coastal communities are home to over 4.6 million people, which represents more than 52 percent of the state’s total population. Action is needed to protect these towns and the people who call them home. But what kind of action?

New Jersey Future analyzed 350 innovative strategies applied in 76 cities or regions that could serve as model initiatives to develop the 15 strategies detailed in the Local Options/Local Actions: Resilience Strategies Case Studies report for the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP).

The strategies are organized into six categories–planning, regulatory, ecological, economic, social, and communications/outreach/education–to provide an accessible and comprehensive menu of options for local officials. No single strategy will yield resilience, and climate risks will fluctuate over time. For this reason, the report recommends local officials consider combinations of strategies tailored for their communities while preparing to pivot to new strategies as risks evolve and risk levels change.

Confronting climate risks can be uncomfortable for local officials and residents to address, but failing to do so will only perpetuate the flood-rebuild-flood practice that puts people and property back in harm’s way without considering future risks. This report can act as a starting point for these discussions and guide towns toward a path of resilient development, fostering safe, healthy, and prosperous communities for generations to come.

Smart Growth Gets Smarter

March 11th, 2020 by New Jersey Future staff

Redevelopment Forum 2020 Highlights: Equity Health Resilience

“Places are more than a town or a city. Places surge lifelong through our bloodstreams. Places are a great unifier. Places help shape our dreams and desires. Places give us so much more of what is required to breathe free and live, live ever higher. Place is so much more than an ‘X’ on a map.” –Pandora Scooter, spoken word artist and Redevelopment Forum performer.

How can we plan smarter and more equitably? These were the important questions considered at New Jersey Future’s 15th annual redevelopment forum. More than 500 planners, developers, local and state officials, and other professionals joined New Jersey Future in New Brunswick at the March 6 day-long conference to look at current redevelopment trends and hear from thought leaders in the field. In his welcome, New Jersey Future Board of Trustees Chair President Peter Reinhart spoke about the evolution of smart growth. Today, all aspects of a redevelopment project and its impact on the community must be considered, with special focus on health, resiliency, and equity. Reinhart urged forum attendees to “keep the big picture of redevelopment in mind and ask yourself how you can play a role in ensuring New Jersey’s redevelopment is the smartest and most inclusive it can be.”

How can we plan smarter and more equitably? These were the important questions considered at New Jersey Future’s 15th annual redevelopment forum. More than 500 planners, developers, local and state officials, and other professionals joined New Jersey Future in New Brunswick at the March 6 day-long conference to look at current redevelopment trends and hear from thought leaders in the field. In his welcome, New Jersey Future Board of Trustees Chair President Peter Reinhart spoke about the evolution of smart growth. Today, all aspects of a redevelopment project and its impact on the community must be considered, with special focus on health, resiliency, and equity. Reinhart urged forum attendees to “keep the big picture of redevelopment in mind and ask yourself how you can play a role in ensuring New Jersey’s redevelopment is the smartest and most inclusive it can be.”

Health

The morning plenary, Building Healthy Communities, featured panelists from various planning-related fields who examined ways in which the built environment impacts the health of the people within it. Moderator Giridhar Mallya, Senior Policy Officer for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, led the panelists in a discussion on how transportation, lack of affordable housing, lead in water, and climate change are impacting health, demonstrating the critical importance of incorporating a culture of health approach into redevelopment planning and implementation.

Morning plenary, Giridhar Mallya, Dr. Adrienne Hollis, Nick Sifuentes, Staci Berger, and Chris Sturm.

Climate scientist Dr. Adrienne Hollis of the Union of Concerned Scientists noted that climate change is a public health emergency with serious impacts experienced in environmental justice communities “first and worst.” New Jersey Future’s Managing Director for Policy and Water, Chris Sturm, discussed a plan to remove lead in New Jersey drinking water over the next decade, stemming from the work of the Jersey Water Works Lead in Drinking Water Task Force. This work was also discussed in a lead-focused morning breakout session moderated by New Jersey Future’s Policy Manager Gary Brune. Nick Sifuentes, Executive Director of Tri-State Transportation Campaign, and Staci Berger, President and CEO of the Housing and Community Development Network of New Jersey, shared the importance of access to transit and safe, affordable housing to the health of individuals and communities.

Resilience

New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection Commissioner Catherine McCabe spoke to forum attendees about the threat of rising sea levels and the steps New Jersey is taking under Governor Murphy’s administration to combat and adapt to climate change, including the signing of two executive orders, emphasizing “if you know what to plan for, you can adapt to it.” Mentioning the effects of sea level rise in his own hometown of Annapolis, President of Smart Growth America’s Leadership Institute and former governor of Maryland, Parris Glendening spoke in his keynote address about climate change and inequity as two of the greatest threats to our future, warning that “we will face both economic and humanitarian crises if we do not start to address (these issues) in a more focused and in a more effective way.” One afternoon breakout session looked at ways in which communities can make transportation, energy, and water systems resilient, and at redesigning these systems to take advantage of new technologies and changing community needs, much like the Gateway Master Plan in the Tampa Bay area.

Governor Parris Glendening, keynote speaker.

Equity

Using redevelopment to achieve more equitable communities was a prominent theme throughout this year’s forum. Equity was a significant feature of the plenary discussion on climate change, infrastructure investment, and affordable housing, and it was in Governor Glendening’s urging of everyone to consider whether each policy reduces or expands inequality, to ensure that people’s lives are not made worse by redevelopment decisions. Equity was the focus of a breakout session on redevelopment strategies to achieve equity, and it was a large part of a session on place-based economic development in downtowns. New Jersey Future Executive Director Peter Kasabach highlighted equity in his remarks, receiving a round of applause in acknowledging “we need to break down segregation in this state and recognize diversity is one of New Jersey’s greatest strengths and one of our most important assets.”

New Jersey Future has made it a priority to incorporate this year’s forum’s core concepts into all of its work. From combatting lead in drinking water, to promoting aging-friendly communities, to working on the State Plan, New Jersey Future aims to create healthy, equitable, and resilient communities where people want to live and work. We hope you will join us. Let’s grow smarter together, New Jersey.

It’s Official: NJDEP Amends State Stormwater Rules to Require Green Infrastructure

March 11th, 2020 by Louise Wilson

In a welcome and important step forward, long-awaited amendments to New Jersey’s stormwater management rules were published in the March 2, 2020 New Jersey Register. The new rule amendments, which take full effect March 2, 2021, require the use of green infrastructure. Green infrastructure refers to a set of stormwater management practices that use or mimic the natural water cycle to capture, filter, absorb and/or re-use stormwater. Access the newly codified Stormwater Management Rules and NJDEP’s FAQ page.

This rule change signals a paradigm shift in New Jersey stormwater management. It replaces a subjective performance standard with an objective standard, and requires that stormwater management features be distributed around a site rather than centralized in one big basin.

What’s the big deal? Stormwater is a big problem, made increasingly worse by climate change and its weather extremes. Stormwater causes flooding and pollutes the streams, lakes and rivers in which we wade, swim, boat and fish. By most estimates, well over 90% of New Jersey’s waterways are polluted. While the new rule does not change underlying standards for water quality, it will result in more stormwater soaking into the earth, and that’s a good thing.

More can and should be done to prevent pollution and reduce flooding. New Jersey Future is working with other stakeholders and NJDEP to formulate additional rule changes aimed at strengthening standards for water quality and stormwater volume control. Meanwhile, we believe the green infrastructure requirement not only will result in more effective stormwater management, but also will confer important societal, public health and economic co-benefits and help communities become more climate resilient.

Interested to know more?

Here are answers to some frequently asked questions:

How do the new stormwater rules differ from the old rules?

The fundamental difference is that the new rules will require decentralized, distributed stormwater management practices that enable stormwater to infiltrate and more closely resemble the natural water cycle. These “best management practices” (BMPs) include vegetated swales, bioretention, green roofs, cisterns, wet ponds, infiltration basins and constructed wetlands.

Here are some specific differences:

- Replaces a subjective performance standard with an objective, math-based standard that requires the use of green infrastructure to meet water quality, quantity, and recharge standards. The rule includes tables showing which green infrastructure BMPs may be used to meet certain standards, and which BMPs may be used only with a variance.

- The water quality standard will apply to “motor vehicle surface” — meaning, paved or unpaved roads, driveways, parking lots, etc. — instead of impervious surface. Consistent with current NJDEP practice, the water quality standard will not apply to impervious surfaces that are not used by vehicles.

- The “major development” definition now includes “creation of one-quarter acre or more of ‘regulated motor vehicle surface’.”

- Water quantity, quality, and groundwater recharge standards must be met in each drainage area on-site (unless they converge before leaving the property).

- A groundwater mounding analysis is required for all infiltration BMPs, not just for recharge.

- A deed notice for stormwater management measures, including green infrastructure, must be recorded and submitted to NJDEP before construction.

- For cities with combined sewer systems (so-called CSS or CSO communities):

- Water quality treatment is required for discharges into combined sewer systems

- Water quantity control is required in tidal areas (except discharges directly into lower reach of major tidal water bodies)

- Community basins, which will allow several properties in a CSS community to use a single large basin for quantity control, are allowed

Consult the amended stormwater rule and the BMP Manual for more detailed information.

Do the published stormwater rule amendments differ at all from what was proposed in December 2018? If so, how?

The rules published on March 2, 2020 are substantively identical to what was proposed in December 2018. The published rules correct a minor typo, and clarify that manufactured treatment devices (MTDs) that meet the definition of green infrastructure may be used without a variance, while MTDs that do not meet the definition of green infrastructure may be used only with a variance.

Does my city or town have to update its stormwater ordinance?

Yes. Every municipality must update its stormwater ordinance to reflect and comply with the new rule language.

Can my local stormwater ordinance impose stricter requirements than are found in the new state stormwater rule?

Yes–local requirements can be stricter in some ways, for certain kinds of projects. In the preamble to its new model stormwater ordinance, NJDEP notes: “Under New Jersey Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System Permits (MS4), the stormwater program may also include Optional Measures (OMs), that prevent or reduce the pollution of the waters of the State. A municipality may choose these stronger or additional measures in order to address local water quality and flooding conditions as well as other environmental and community needs. For example, municipalities may choose to define “major development” with a smaller area of disturbance and/or smaller area of regulated impervious cover or regulated motor vehicle surface; apply stormwater requirements to both major and minor development; and/or require groundwater recharge, when feasible, in urban redevelopment areas.”

Note: these kinds of higher standards can be applied only to nonresidential projects that go before the local planning board or zoning board of adjustment. Residential projects are governed by the Residential Site Improvement Standards (RSIS), which reference the current stormwater rule. Thus, residential projects subject to planning board or zoning board review must meet the state’s minimum standards, no more and no less. That said, some developers are willing to exceed the state’s minimum standards in the interest of environmental protection, return on investment, marketing, and/or other community interests.

Will there be an organized effort to train professionals and practitioners who need to understand green infrastructure?

Yes. NJDEP, Rutgers University, and the Watershed Institute will conduct training for design professionals and for those who construct, inspect and maintain green infrastructure BMPs. In addition, education and training likely will be available through other experts and interested parties — public sector and private sector — including NJ Society of Municipal Engineers, private engineering firms, ASLA-NJ, APA-NJ, and New Jersey Future.

The Best Is Yet To Come: New Jersey Future Helps Towns Become Great Places to Age

March 9th, 2020 by New Jersey Future staff

New Jersey Future recently held kickoff meetings in Pompton Lakes in Passaic County and Ridgefield Park in Bergen County as part of its Creating Great Places to Age program, which helps towns ensure that older residents can continue living in their communities and remain active, healthy, and engaged.

Every day for the rest of the decade, 8,000 members of the Baby Boom generation will turn 65. Given their increasing number of aging residents, towns across the country should be including aging-friendly factors in local planning, such as housing affordability and diversity; transportation; walkability; and access to daily tasks,activities and socialization.

Pompton Lakes meeting.

Land use is a critical factor in a town’s livability for people of all ages, but especially for older residents.. Through support from The Henry and Marilyn Taub Foundation, New Jersey Future is working with towns to conduct aging-friendly land use assessments and assist with local planning based on the results. As part of the assessment process, New Jersey Future analyzes a town’s downtown center, housing options, access to transportation, and supply of public spaces and amenities, and then provides recommendations for each in an Aging-Friendly Land Use Assessment report.

Members of the Pompton Lakes and Ridgefield Park Aging-Friendly Land Use Steering Committees participated in their respective February and November kickoff meetings with New Jersey Future to learn about aging-friendly community building and begin the engagement component of the assessment process. The towns’ diverse steering committees are comprised of members from local and county government, community and senior groups, and from the professional fields of public health, engineering, and planning.

Wanaque Ave., Pompton Lakes NJ

Pompton Lakes and Ridgefield Park are suburban towns with populations of approximately 11,000 and 13,000, respectively. Both towns have well-defined mixed-use downtowns, which is typical of many of New Jersey’s older suburban towns that pre-date the rise of the automobile. Similar to New Jersey as a whole, over 25 percent of both towns’ residents are 55 and older. However, both towns are much more developed than the state as a whole. Pompton Lakes and Ridgefield Park are both nearly 100 percent built-out, meaning that almost all the land that can be built on has already been used. Pompton Lakes is currently working to support redevelopment projects and Ridgefield Park is working on a Master Plan update, making the time for New Jersey Future’s planning work with each town ideal.

Pompton Lakes and Ridgefield Park are two of eight towns currently working with New Jersey Future in becoming more aging-friendly. Want to make your own community more aging-friendly? You can find resources on New Jersey Future’s page about creating great places to age.

It’s Official: NJDEP’s Stormwater Rule Changes Published in the New Jersey Register

March 2nd, 2020 by Louise Wilson

On March 2, important changes to the state’s stormwater management rules (NJAC 7:8) were published in the New Jersey Register. Access the amended rules.

On March 2, important changes to the state’s stormwater management rules (NJAC 7:8) were published in the New Jersey Register. Access the amended rules.

These amendments to the stormwater rules have been in the works for years. They include a requirement that green infrastructure must be used to meet stormwater management standards for water quality, groundwater recharge and quantity control. This new requirement replaces a requirement that major developments incorporate non-structural stormwater management strategies “to the maximum extent practicable.” Over time, the “maximum extent practicable” standard proved ineffective.

The rules published today appear to be substantively identical to what was proposed in December of 2018. A 12 month implementation period begins today.

In addition to the new rule language, DEP is updating key chapters of its Stormwater Best Management Practices (BMP) Manual and soon will make available a sample ordinance, which municipalities can use as a reference to ensure that required updates to municipal stormwater ordinances meet, at a minimum, the state’s new requirements.

In the coming weeks, New Jersey Future will update the Green Infrastructure Municipal Toolkit and the Developers Green Infrastructure Guide to reflect new rule requirements and related resources. Stay tuned!

Climate-Ready CSO Solutions Forum

February 20th, 2020 by Moriah Kinberg

New Jersey Communities Discuss Climate Change Impact on Multi-Billion Dollar Sewer Improvement Plans

In New Jersey, 21 fast-growing communities with outdated sewer systems that combine rainfall with industrial and domestic sewage are finding they are particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change. When it rains in these communities, raw sewage pours into rivers and backs up into basements and onto streets, known as Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO). Increased flooding from sea level rise, more intense storms, and extreme heat due to climate change are compounding the existing environmental and health concerns in New Jersey’s CSO communities.

New Jersey Future hosted this event in partnership with the Sewage-Free Streets and Rivers campaign and the New Jersey Climate Change Alliance on January 28 in the city of Elizabeth to discuss the importance of the state’s CSO communities incorporating climate change as a critical factor in planned upgrades to wastewater infrastructure systems.

Attendees were concerned about the impact of climate change on their communities.

Approximately 80 community members, engineers, utility directors, environmental advocates, students, design professionals, and media attended the forum at which CSO and climate change experts discussed integrating climate change solutions into CSO Long Term Control Plans (LTCPs). The communities’ LTCPs are due to the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) by June 1 and will be implemented over the next 30-50 years while towns are simultaneously battling climate change. Governor Phil Murphy recently signed Executive Order 100, which requires the integration of climate change and sea level rise into the state’s regulatory and permit programs, including CSO permits.

Forum panelists included New Jersey Future Executive Director and panel moderator Pete Kasabach; Elizabeth Mayor J. Christiam Bollwage; Dave Rosenblatt, New Jersey’s first Chief Resilience Officer; Janice Brogle, Acting Director of Water Quality for NJDEP; Dr. Marjorie Kaplan, Associate Director of the Rutgers Climate Institute; Andy Kricun, Executive Director and Chief Engineer for the Camden County Municipal Utilities Authority; Alan Cohn, Managing Director of Integrated Water Management for the NYCDEP; Kim Gaddy, Environmental Justice Organizer for Clean Water Action; and Jackie Park Albaum, Director of Urban Agriculture for Groundwork Elizabeth.

The panelists discussed adding green infrastructure to towns as a solution to help reduce CSOs as well as flooding and extreme heat due to climate change. The need for creative solutions to address the impacts of climate change related to CSOs was highlighted, as was the importance of environmental justice and engaging communities in solutions. Cost was a prominent topic of discussion, given that the wastewater infrastructure improvements are expected to cost billions of dollars. Implementing the plans will have significant effects on residents and business owners in the CSO communities for generations to come.

Go Home and Ask Questions

Attendees were urged to continue the conversation started at the forum in their own communities and with their elected officials and utilities by asking them how they are considering climate change in selecting alternatives to CSOs. Three important questions residents can ask are:

- How are the alternatives to CSOs being designed to withstand the impacts of sea level rise and increased precipitation caused by climate change?

- How are social vulnerabilities to climate change being taken into consideration? For example, are maps being developed that show flooding and combined sewer outfalls in relation to income, minority status, race, and age?

- Are the communities who will be impacted by climate change being taken into consideration in the selection and siting of alternatives to CSOs?

New Jersey Future is a state leader in the area of wastewater infrastructure, including CSOs, as part of its mission to make smart investments in infrastructure to increase New Jersey’s competitiveness and support healthy communities where people want to live and work.

Join the Sewage-Free Streets and Rivers campaign today to stay up-to-date on the process and opportunities to review and comment on the CSO LTCPs.

Resources:

Sewage-Free Streets and Rivers – Community engagement and outreach resources on combined sewer overflows and contact information for municipal and utility permit holders.

New Jersey Climate Change Alliance – Information on sea level-rise and the impacts of climate change on New Jersey.

New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection Combined Sewer Overflow Basics – New Jersey Combined Sewer Overflow permit submissions and information on the permit process.

Groundwork USA Climate Safe Neighborhoods – Maps that show the connection between housing discrimination and climate change and how Groundwork communities are using maps and data to build resilience to extreme heat and flooding.

New Jersey’s Supply of Developable Land Is Shrinking – As a Result of Both Development and Preservation

February 17th, 2020 by Tim Evans

Recently-released 2015 land use/land cover data from the Department of Environmental Protection offer an opportunity to assess the state of land development in New Jersey.

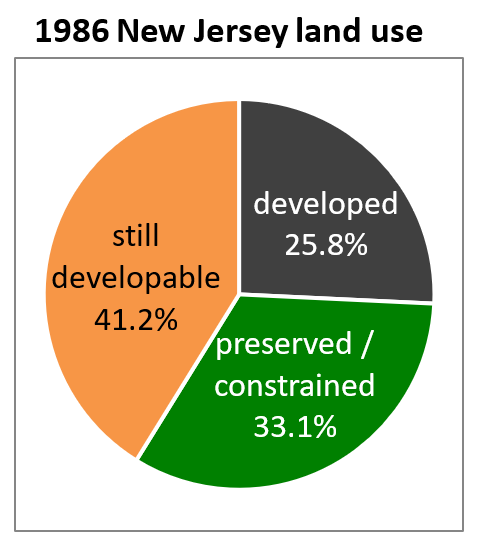

New Jersey is the nation’s most developed state, and it gets more developed every year. In 1986, the first year in which detailed land-use data were available from the Department of Environmental Protection, about one quarter (25.8 percent) of the state’s total land area was developed. Another third – 33.1 percent – was either permanently preserved or subject to other regulation that rendered it undevelopable.[1] This left 41.2 percent of the land in New Jersey still developable as of 1986.

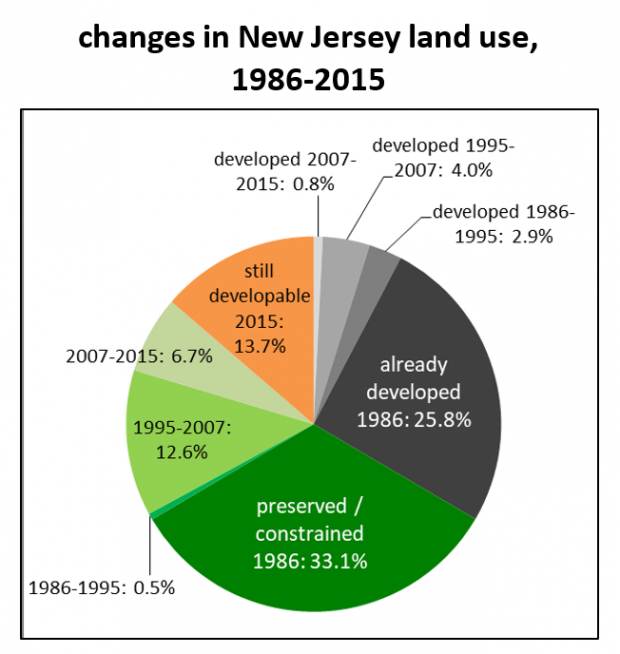

The DEP data, and the add-on analysis by the Rowan/Rutgers research team, have been produced at irregular intervals since 1986, with data points for 1986, 1995, 2002, 2007, 2012, and 2015. When combined, they present an informative portrait of how New Jersey’s land-use priorities have evolved over the last three decades.

On the development side, note that New Jersey started at about ¼ of the way developed in 1986 and proceeded to develop an additional 2.9 percent of its land between 1986 and 1995, another 4.0 percent between 1995 and 2007 [2], and a comparatively minor 0.8 percent between 2007 and 2015.

The pace of preservation has followed a decidedly different trajectory. Note that the amount of land taken off the market for development via preservation or regulation between 1986 and 1995 was negligible – a mere 0.5 percent, or a little less than 26,000 acres, during a period when 134,000 undeveloped acres were converted to urban uses. Land was being developed at more than five times the rate of preservation. But between 1995 and 2007, a dramatic role reversal happened: The pace of preservation outstripped development by a factor of three, with 590,000 new acres being placed off limits to development compared to 190,000 acres being newly developed. This was the era in which Governor Christine Todd Whitman articulated a goal of preserving an additional million acres of open space, elevating in the public consciousness the issue of development pressure on the state’s remaining open lands and leading to the creation of the Garden State Preservation Trust to advance the new goal.

The new focus on saving open lands has continued in the most recent data period. Both development and preservation dropped off between 2007 and 2015, but the disparity between the rates grew even larger; the number of acres taken out of the “developable” pool via preservation or regulation (313,000) was more than eight times the number of acres that were newly urbanized (a little less than 37,000).

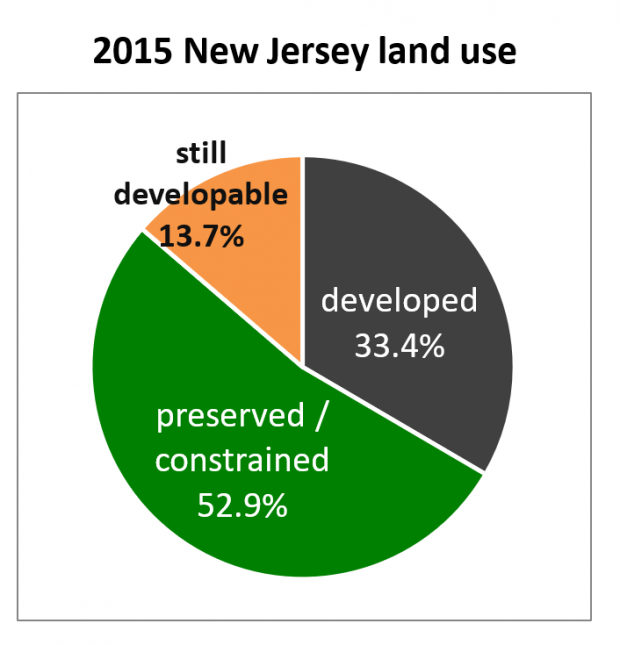

The end result is that, from 1986 to 2015, the state has gone from one-quarter developed to one-third developed but also from one-third preserved or constrained to more than half. As of 2019 [3], 52.9 percent of the state’s total land area – some 2.48 million acres – consists of undeveloped land that has been protected from development, up from about 1.58 million acres in 1995, just before the million-acre goal was established.

The twin forces of development and preservation, having both been hard at work over the last 30 years, have resulted in the state’s supply of still-developable land dropping from 41.2 percent of its total land area in 1986 to just 13.7 percent in 2015 (factoring in additional preserved land through 2019). While the fact that we have saved so many of our remaining open lands from development is good news, it does mean we will have to be ever more judicious about how we use our diminishing supply of developable land, and it should help cement the idea that the future of development in New Jersey is redevelopment.

[1] Based on additional analysis by researchers at Rowan and Rutgers universities that overlays the DEP data with other data sources that describe lands that have been permanently preserved or are otherwise regulated and cannot be developed

[2] For simplification purposes, the 1995-2002 and 2002-2007 intervals have been combined, as have the 2007-2012 and 2012-2015 intervals.

[3] The Rowan/Rutgers complementary analysis uses preservation data up through 2019, on top of the 2015 DEP development data.

Does the Retail Apocalypse Mean the End of Downtowns?

February 17th, 2020 by Peter Kasabach

For the first time in the United States, consumers spent more at restaurants and bars than grocery stores. This is just one of many statistics that drives home the point that where and how people spend their money is changing. And these consumer habits are changing the look and viability of our state’s downtowns.

For the first time in the United States, consumers spent more at restaurants and bars than grocery stores. This is just one of many statistics that drives home the point that where and how people spend their money is changing. And these consumer habits are changing the look and viability of our state’s downtowns.

New Jersey Future and JGSC Group presented Does the Retail Apocalypse Mean the End of Downtowns? at the annual American Planning Association–New Jersey conference held on January 23rd in New Brunswick. The answer to that apocalyptic question was a resounding “maybe”.

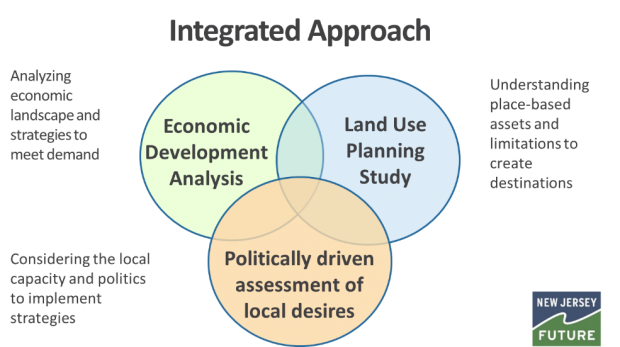

Town leaders that are proactive and see the future of their downtowns as compact, walkable, thriving centers will gain the competitive advantage. These same town leaders are normally presented with one of three avenues for how to make this happen:

- Economic development study. This type of study analyzes demographic and market data and lets you know what commercial opportunities might exist to attract growth. It generally doesn’t look at your assets, housing, your vision or how you might accomplish this task.

- Land-use planning study. A land-use planning study helps you understand the built environment and changing demographics and desires, especially for compact, walkable places. It doesn’t look beyond the physical assets at the realistic market opportunities, oftentimes assuming demand.

- Politically driven study based on local desires. This locally-driven process builds support from the community for what it wants to see and therefore what can be politically supported. It doesn’t provide a reality check based on demographic, market or practical realities.

Too often, towns pursue one of these approaches and are typically disappointed when the individual study does not lead to implementation steps or real change.

The panel of Peter Kasabach (New Jersey Future), Joe Getz (JGSC) and Mark Lohbauer (JGSC) looked at these different approaches and presented an integrated model that combines elements of all three of these methodologies. A convincing case was made that when combined, the result is a visionary plan, grounded in reality that is implementable. New Jersey Future and JGSC are currently working together to advance this approach in the town of Bloomingdale.

New Jersey Losing Population for the First Time in Four Decades

January 16th, 2020 by Tim Evans

A long-term decline in the national birth rate and a recent drop-off in immigration have joined forces with ongoing out-migration to other states to produce New Jersey’s first population loss since the late 1970s.

A long-term decline in the national birth rate and a recent drop-off in immigration have joined forces with ongoing out-migration to other states to produce New Jersey’s first population loss since the late 1970s.

The Census Bureau recently released its annual national and state population estimates for 2019, and there is some notable news for New Jersey: New Jersey has now joined the ranks of states that are losing population. Granted, it is a very small loss, with the state’s population declining by an estimated 3,835 residents, or 0.04 percent, from 2018 to 2019. And New Jersey has plenty of company: Nine other states have also lost population since 2018 – Alaska, Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Louisiana, Mississippi, New York, Vermont, and West Virginia. All but Vermont and Alaska lost more residents than New Jersey did, and New Jersey’s was the smallest loss in percentage terms.

Still, this is the first time since the dark days of the 1970s, when large urban areas throughout the Northeast and Midwest were hemorrhaging population, that New Jersey has experienced a year-over-year population loss. The state lost 1,959 people from 1972 to 1973 and another 674 from 1973 to 1974; lost 2,575 from 1976 to 1977; and lost 1,691 between 1979 and 1980. Since 1980, though, New Jersey has managed to stay above water, even when other Northern states (and a few Southern ones) experienced periodic year-to-year losses.

Why has New Jersey now lapsed into actual population decline for the first time in 40 years? One contributing factor is that New Jersey loses more domestic migrants to other states than it attracts from other states. New Jersey Future has pointed to New Jersey’s net domestic outflow before, particularly among Millennials. Between 2018 and 2019, New Jersey lost a net of just under 49,000 people due to domestic migration (that is, about 49,000 more people left New Jersey to move to other states than people who moved to New Jersey from other states). But this net out-migration is not new. New Jersey has lost at least 45,000 net domestic migrants every year of the 2010s, with individual annual losses reaching as high as almost 67,000 between 2015 and 2016. The 2018-19 loss is actually among the smaller ones this decade. Net domestic out-migration, while an ongoing concern, has not gotten any worse in the last year, so we must look to the other components of population change to explain the overall loss.

In past years, immigrants to New Jersey from other countries have roughly counterbalanced out-migrants to other states, with the result that immigration plus natural increase (births minus deaths) has provided New Jersey with a small net positive growth rate. But not this year. The big story from this year’s state population estimates is the dramatic decline in net international migration nationwide. At the national level, according to the Census Bureau’s press release, immigration is down from 1,047,000 in 2016 to only 595,000 in 2019, a drop of 43 percent. New Jersey, traditionally one of the country’s top immigrant magnets, has experienced an even bigger dropoff, from a net 50,087 international immigrants between 2015 and 2016 down to only 21,284 between 2018 and 2019 — a decline of more than half. Such a reduced rate of immigration, if it persists, would no longer be enough to offset New Jersey’s steady loss of domestic migrants to other states, meaning that New Jersey – and New York, and Illinois, and other states that have recently been relying on immigrants to compensate for domestic out-migration, possibly soon even including California – could be on a path toward sustained population loss.

Another factor at work is more of a long-term phenomenon – a decline in “natural increase,” which is the difference between births and deaths. (This is what population change would look like if no one ever moved across state borders or between the United States and other countries.) Birth rates have been declining throughout the industrialized world, and the United States has been no exception. Meanwhile, we should expect the number of deaths to increase in the next two decades as the Baby Boomers – the largest generation in American history until their children, the Millennials, recently overtook them – begin reckoning with mortality in large numbers. (The oldest Boomers turn 74 this year.) As another sign of this graying of the population, the Census Bureau estimates that by 2030, people over the age of 65 will outnumber those under 18 for the first time in US history.

The Census Bureau’s press release about 2019 state populations points to the fact that natural increase nationwide dropped below 1 million in 2019 for the first time in decades, whereas it had held steadily above 1.5 million annually throughout the 2000s and was still above 1.3 million as recently as 2015. During the 2000s, New Jersey’s natural increase averaged around 41,000 per year, ranging from a low of 38,795 between 2008 and 2009 to a high of 46,272 between 2007 and 2008. But natural increase declined steadily in the 2010s, from an increase of 35,620 between 2010 and 2011 all the way down to 23,778 between 2018 and 2019.

West Virginia and Maine have been experiencing natural decreases (where the number of deaths exceeds the number of births) for the whole second half of this decade, and this year they are joined by Vermont and New Hampshire. Such decreases will probably continue to show up in more and more states in the coming decade, especially if Millennials continue to not have children at the same rate as previous generations. In West Virginia and Vermont, neither of which attract many immigrants from other countries and both of which typically lose domestic migrants to other states, a declining rate of natural increase has already translated into overall population loss; both states have experienced year-to-year population losses more than once in the 2010s. Maine and New Hampshire have continued to grow mainly by attracting domestic migrants from Massachusetts; without these new arrivals from Metro Boston, they would be in much the same position as Vermont.

If a dramatically reduced immigration rate turns out to be the new normal instead of a temporary disruption, and as the more long-wave phenomenon of declining rates of natural increase begins to make itself felt, state population growth in the United States may come to resemble a zero-sum game, where any state’s growth must necessarily result in some other state’s loss. If such a scenario comes to pass, New Jersey, with its established pattern of out-migration to Pennsylvania and to Southeastern states like Florida, Virginia, and North Carolina, may evolve into one of the nation’s biggest population “donor states.” New Jersey has control over neither national immigration policy nor a declining birth rate that is common to most of the industrialized world. Nor can it change the weather, which has been luring retirees to Florida for many decades. But if the state cannot find a way to make itself more affordable to younger generations and allow people to stay here or move here even when they want to, this year’s small loss could be a harbinger of larger problems down the road.