New Jersey Future Blog

Stuck with Stormwater Issues? See Expert Solutions to Fight Flooding and Pollution in the Updated Municipal Toolkit

November 10th, 2020 by Andrew Tabas

If your town experiences localized flooding and degradation of nearby waterways due to stormwater runoff, there is a sustainable solution that can help. Green infrastructure (GI) can make your town a healthier, cleaner, and safer place to live by reducing flood risk, returning clean water to the ground, cleaning and cooling the air, and aiding in pedestrian safety.

Not only is green infrastructure a sustainable and effective tool to manage stormwater that all municipalities should implement, the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) now requires new public and private major developments to manage stormwater runoff with green infrastructure. This Spring, the NJDEP published the new Stormwater Rules (NJAC 7:8), which take effect March 2, 2021. As the private sector builds more GI to comply with the rule amendments, elected officials and residents will see the resulting increased economic, environmental, and public health benefits.

To achieve the maximum benefit from GI while balancing many priorities, municipal leaders need comprehensive, practical guidance in order to take action. New Jersey Future’s newly updated Green Infrastructure Municipal Toolkit is a one-stop green infrastructure resource designed to help municipal leaders and advocates address the related problems of nuisance flooding and polluted waterways. The new updates will help municipalities leverage the rules to work with developers, understand the effect of the rules, and organize the approval of green infrastructure projects.

The Green Infrastructure Municipal Toolkit, updated in November 2020, contains resources to help municipal leaders to encourage the implementation of green infrastructure.

What Municipal Requirements Do NJDEP’s Stormwater Rules Include?

The key takeaway from the Stormwater Rule amendments for municipal governments is that municipalities are required to update their municipal stormwater control ordinances by March 2, 2021 to comply with the new rules. To assist municipalities with this update, NJDEP has released a model ordinance and indicates that municipalities may go above and beyond the state’s minimum standards to increase the benefits described above. New Jersey Future’s toolkit lists a few ways to do that:

- Reduce the definition of major development so that it applies to smaller projects in order to increase the number of projects that use green infrastructure, which will in turn reduce flood risk across your entire municipality.

- Extend the requirement for green infrastructure to redevelopment projects in order to mitigate the negative effects of stormwater runoff from existing developments.

- Require the retention of at least 1.25 inches over two hours onsite, which eliminates flooding from 90% of New Jersey’s rain events.

Green infrastructure improves stormwater management and beautifies cities. Photo credit: Andrew Tabas.

Updated ordinances will affect both public and private development projects. For public developments, municipalities will need to collaborate with contractors to ensure that green infrastructure is built according to the best standards. For private developments, the rules provide a pathway for municipalities to work with developers to increase the use of green infrastructure on private land. The toolkit provides resources that are applicable to both public and private projects.

What to Do Next

So, what else can you do to bring the benefits of green infrastructure to your town? Visit the newly updated Municipal Toolkit to check out the following resources.

First, use these checklists to ensure that green infrastructure projects are designed, built, and maintained effectively:

- NJDEP’s “Checklist for Conducting Stormwater Management Reviews.” This checklist presents a straightforward process for municipal boards to approve projects, which makes it easier to ensure that each phase of the project is completed correctly. It includes everything from soil testing to water quality, water quantity, and groundwater recharge requirements.

- Municipal Stormwater BMP Inspections Checklist. This will help municipal engineers to inspect sites during construction. It provides a straightforward way to know which components need to be inspected for each green infrastructure Best Management Practice (BMP).

- Monitoring Logbook. The monitoring logbook will help municipalities to keep track of ongoing monitoring and maintenance activities to ensure GI BMPs are functioning properly.

Second, to get a sense of the improvements that green infrastructure could bring to your municipality, check out these two side-by-side comparisons:

- The Mixed Use Comparison shows the improvements to stormwater management under the updated Stormwater Rule. The example site is able to count infiltration in its stormwater management calculations, which makes it possible to increase the use of bioretention systems while decreasing the size of gray infrastructure. The site also uses a decentralized approach to stormwater management, with green infrastructure distributed throughout the site.

- The Green Streets Comparison demonstrates the benefits of turning a traditional street into a green street. These include improved stormwater management, more beautiful streets, increased accommodation for walkers and cyclists.

Green streets are pedestrian-friendly alternatives to traditional streets. See the toolkit for a side-by-side comparison of green and traditional streets. Graphic designed by E&LP for NJF.

Third, visit the toolkit’s resources page to check out additional resources that are useful for municipalities, including a maintenance manual, case studies on green streets, and a presentation on harmful algal blooms.

Municipalities have an exciting new opportunity to gain green stormwater upgrades through new development and redevelopment. For more updates, sign up for our mailing list!

The Green Infrastructure Municipal Toolkit is a product of New Jersey Future’s Mainstreaming Green Infrastructure program.

Visualizing an Aging-Friendly Built Environment for Implementation in Ridgewood Village

November 10th, 2020 by Tanya Rohrbach

Communities in New Jersey and across the country are responding to the need to design their built environments with older residents in mind. Our population is aging, and towns are taking steps to create better places for people to live during their later years. Considerations include creating housing that is of diverse type and more affordable, providing for greater mobility, and enhancing public spaces to be more accessible, safer, and welcoming.

New Jersey Future partnered with the Village of Ridgewood to develop the Creating Great Places to Age: Aging-Friendly Land Use Implementation Plan for the Village of Ridgewood. The plan identifies a number of aging-friendly strategies the town can pursue based on an implementation planning process that New Jersey Future facilitated. The process prioritized recommendations of the aging-friendly land use analysis completed previously for the village by New Jersey Future. Four high-priority strategies are detailed in the plan and include the specific action steps the town would need to take to implement each.

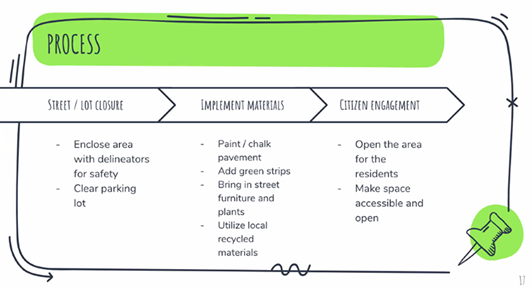

To provide design support to the village for one of the plan’s action items, a graduate design studio class at the Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy at Rutgers University worked from the town implementation plan and presented five tactical urbanism design concepts for several community locations to village engineers and council members. The students developed design concepts that involve installation of a temporary demonstration project to test a more permanent solution or that will provide a low-cost community amenity that is adaptable to changing needs. This approach is often referred to as tactical urbanism and is a great way for municipalities to take actions with community involvement.

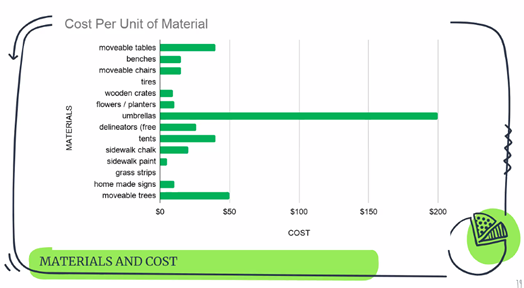

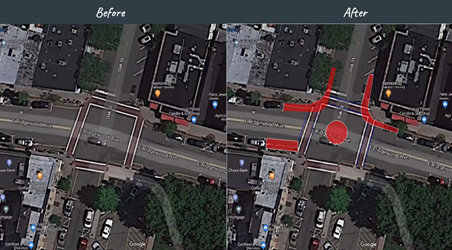

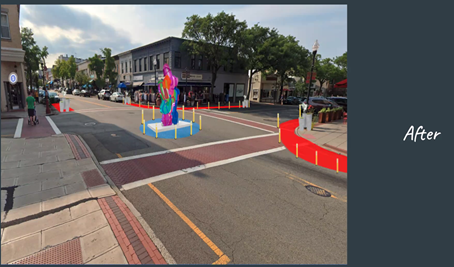

Students presented visualizations for tactical urbanism designs to improve walkability, create a more welcoming park space, adapt outdoor dining and retail for winter activities, and redesign certain intersections with traffic-calming installations. All of the design concepts incorporated low-cost materials and modular components so that Ridgewood could implement meaningful improvements without spending a lot of money or committing to major infrastructure changes. For example, students pointed out the lack of a crosswalk and insufficient seating at Van Neste Square Memorial Park, which is located about two and a half blocks from the train station and centrally located in the downtown business district. The design recommendations for this space included installation of a decorative crosswalk, additional seating, and flower gardens that would all be developed based on a community engagement process to identify stakeholder issues and solutions and subsequent documentation through observation to modify the design as needed.

Another design concept for the park showed a plaza extension to better accommodate the park’s use as a location for events, gatherings, and outdoor leisure and exercise activities. The extension proposed uses an existing adjacent parking area to install temporary, modular chairs, tents, planters and other features that would change with the seasons and adapt with community needs. These kinds of designs are intended to improve pedestrian safety, attract people to the area for community engagement, and support businesses at a very low cost to the town.

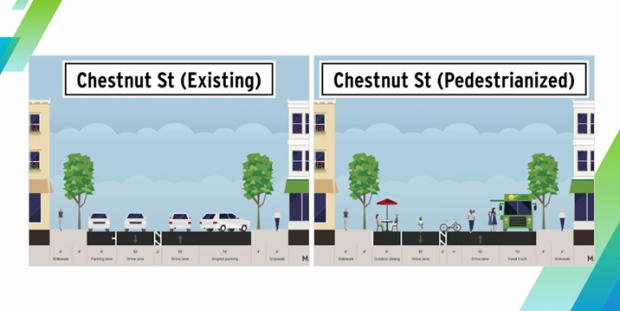

Students recognized the work Ridgewood has already done to respond to the effects of COVID-19 on local businesses by permitting outdoor operation of dining and retail under certain conditions and closing some streets to vehicular traffic to permit pedestrian-only use at certain times. To provide a means for Ridgewood to winterize these activities beyond the current set up of basic tables, chairs, and umbrellas, students presented examples of different types of enclosures that could be constructed, modified, or dismantled easily and are low-cost. Sketches of parklet models showed semi-enclosed spaces constructed of pallets and included recommendations for storage options, drainage considerations, accommodation of different sized groups, and even carnivorous plants. Designs for repurposing street space and some parking spaces for outdoor activities were offered as a means to create temporary outdoor dining and retail spaces that would be more welcoming to pedestrians and provide more benefits to businesses able to operate outside their establishments.

Intersection and circulation improvement designs presented by the students included bicycle lanes, island extensions, curb bump-outs, and a roundabout constructed with an art installation. What makes these design concepts feasible and desirable is their low cost, relative ease of installation, and adaptability to community input and needs. If the temporary installation of traffic cones and painted streets demonstrates improved pedestrian safety and activity, for example, the municipality could then pursue a more permanent solution. In the process, community stakeholders can take part in creating the temporary installation and interact with the design to provide input for a permanent improvement.

At the student presentation, the mayor of Ridgewood offered insight to contextualize the designs and suggest design modifications and expressed an overall pleasure with how the concepts added color and pedestrian-oriented community spaces to the downtown. All of the design concepts demonstrated that age-friendly design also benefits residents of all ages and is compatible with creating a vibrant downtown economy centered on pedestrian-oriented civic spaces.

Does School District Fragmentation Support Residential Segregation?

November 9th, 2020 by Tim Evans

Geography of Equity and Inclusion Series. There are many causes of racial and economic segregation in New Jersey. In our Geography of Equity and Inclusion series we look at some of the issues and dynamics that help us better define the problem, its causes, and system changes needed for reversing. Today’s installment looks at the relationship between school district fragmentation and the role it may play in fostering and maintaining a racially and economically segregated state.

New Jersey has an overabundance of small school districts when compared nationally

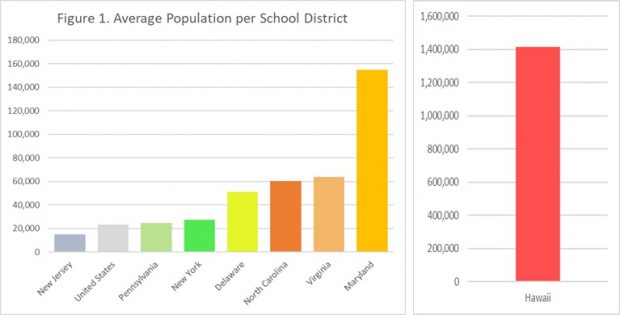

The level of government at which public schools are operated and funded varies widely from one part of the country to another. New Jersey’s public school landscape is particularly fragmented—it averages 28 school districts per county, the most of any state, and averages just under 15,000 residents per school district, well below the national average of 23,344. New Jersey Future has written about how New Jersey’s fragmented collage of public school districts leads to land-use incentives that discourage residential development. We are interested in exploring whether this fragmented system may also contribute to residential segregation, both by income and by race.

New Jersey Future has compared New Jersey’s 21 counties with a set of counties in nearby states (including some that are major destinations for New Jersey out-migrants) where the provision of public education is organized differently, to see if the degree of fragmentation appears to be related to the degree to which certain disadvantaged groups (lower-income, Black, and Hispanic populations) tend to be concentrated in relatively few neighborhoods. We included in the comparison a number of counties in states where schools are run at the county level, as well as looking at statewide data in Hawaii, which is unique in having a single statewide school district. County-run school districts—as in Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina—generally serve much larger populations than those run at the sub-county level, as they are in New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and Delaware (see graphic).

There is a relationship between district fragmentation and segregation

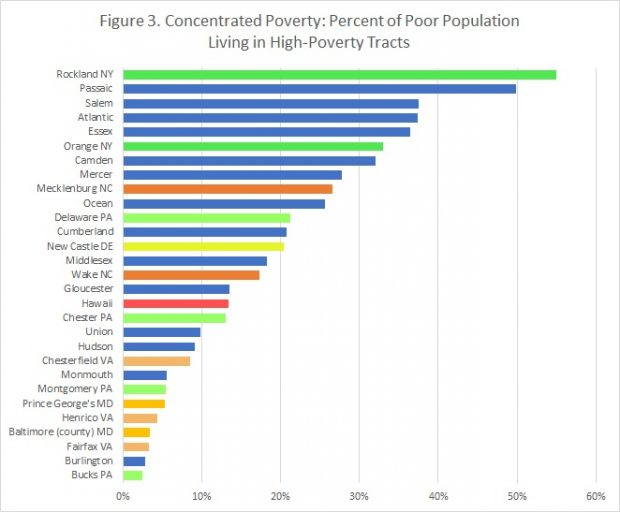

The results of our analysis strongly suggest a relationship between the degree of fragmentation in the organization of public education and the degree of residential segregation. The same incentives that intensify both competition for commercial and industrial properties and resistance to residential development when the units of competition are smaller also appear to result in higher degrees of segregation by race and by income. For example, when looking at what percent of a county’s poor population lives in a high-poverty neighborhood (see graphic), it is counties in New Jersey and New York—the two states with the most fragmented systems of public education—that dominate the top of the list. Meanwhile, the counties with countywide school systems are generally clustered near the bottom. Even the two North Carolina counties, which are each dominated by a single large city, outperform many of the New Jersey counties on the list, despite the fact that large cities are where high-poverty neighborhoods are most frequently found.

Results are similar for segregation by race, where counties with countywide school districts tend to have smaller percentages of their Black and Hispanic residents living in majority-Black or majority-Hispanic neighborhoods, respectively, relative to the overall sizes of their minority populations than is true in counties with more fragmented school districts like New Jersey’s.

More localized responsibility for school funding appears to make discriminatory impulses not only more of a cold, calculated fiscal strategy but also easier to carry out via localized land-use decision-making. If we want to address New Jersey’s status as one of the most segregated states in the country, mitigating these incentives by organizing and funding public education at a higher level of government might be a good place to start.

See the full report here.

Stormwater Utilities—Peeling Back the Onion

November 9th, 2020 by Gary Brune

Ever since Governor Murphy signed legislation in March 2019 providing communities with the option of creating a stormwater utility to address flooding and water quality issues, two key questions have loomed: how much do municipalities and counties currently spend on stormwater infrastructure, and how receptive are they to this new concept?

In its 2020 Best Practices Inventory, the Department of Community Affairs (DCA) will ask localities both questions. The results should shed light on the current level of effort, potential funding gaps, and the willingness to explore a solution that, for some communities, might represent a more equitable way to achieve their long term vision.

Specifically, DCA’s 2020 inventory survey will have three new questions:

- How much did your municipality spend on operational costs for managing and treating stormwater runoff (e.g., street cleaning, pipe system cleanouts, storm drain/outfall maintenance, public education) last fiscal year and how much was appropriated for the current fiscal year?

- Which projects in your municipality’s most recent adopted capital budget, if any, are associated with stormwater management?

- Is your municipality either considering establishing a stormwater utility or authorizing a sewerage authority or municipal utility authority to establish a separate stormwater operation?

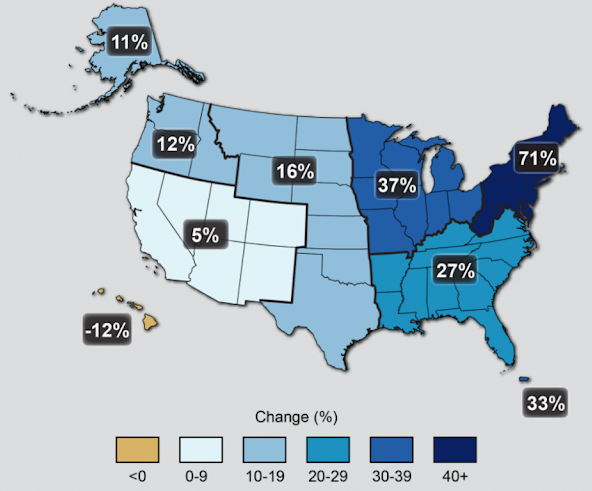

Why is this so important? In New Jersey, stormwater infrastructure needs have traditionally been funded through local property tax revenue, and with local budgets hard-pressed to address high profile issues such as schools and law enforcement, stormwater projects are often deferred or discounted. Chronic flooding threatens public safety, snarls traffic, and chokes economic growth. The forecast portends more of the same. Based on storm patterns since 1958, a National Climate Assessment study issued in 2015 documented a 71% increase in the severity of heavy storms affecting northeastern states such as New Jersey. (See graphic below.) Stormwater is also responsible for approximately 60% of water quality problems in the state, including harmful algae blooms that regularly plague freshwater lakes.

Observed Change in Very Heavy Precipitation, 1958 – 2012

Source: 2015 US Climate Resilience Toolkit, National Climate Assessment

Since there is no relationship between the value of a property and the amount of stormwater runoff, the property tax is a particularly poor funding source for this critical need. Similar to existing sewer and water utilities, a stormwater utility employs a more equitable user fee approach, with charges based on a given property’s degree of impervious coverage (e.g., hardened surfaces, such as driveways) that generate runoff. Under a stormwater utility, costs are more equitably allocated based on each property’s contribution to the problem.

Survey responses, which are mandatory, are due to DCA’s Division of Local Government Services by November 3, 2020. And since ongoing budget language links receipt of local aid payments from the Consolidated Municipal Property Tax Relief program to satisfactory completion of the Best Practices Inventory, a high level of compliance is anticipated. The Department plans to compile the responses into a summary report.

Detailed information about DCA’s Best Practices Inventory may be found in Local Finance Notice 2020-20 (see https://www.nj.gov/dca/divisions/dlgs/lfns/20/2020-20.pdf).

For a comprehensive overview of stormwater utilities, including key policy, legal, and financial issues, consult the recently-launched New Jersey Stormwater Resource Center at https://stormwaterutilities.njfuture.org/. The Center, prepared by New Jersey Future, is tailored to provide both basic and technical information for interested residents and local officials.

An Interview with 2020 Cary Edwards Leadership Award Winner Peter Reinhart

November 9th, 2020 by New Jersey Future staff

New Jersey Future is honoring Peter Reinhart this year for his decades of service and commitment to fair and affordable housing, for bridging real estate development and smart growth, and for his years of leadership on progressive land use policy throughout the state and with the New Jersey Future Board of Trustees. Join New Jersey Future for a virtual celebration of the 2020 Smart Growth Awards on December 15.

Q: You are known for your commitment to affordable housing. Can you speak about your work and how you became involved in this area?

A: When I was in Rutgers Camden Law School in the early 1970’s, the first Mount Laurel decision came down and I was introduced to the long history of housing segregation and the efforts underway to reverse it. In 1983, while I was serving as general counsel at K. Hovnanian Enterprises, the New Jersey Supreme Court decided Mount Laurel II, requiring municipalities to provide housing for low- and moderate-income families. The company made a smart business decision to seek out opportunities to build “inclusionary developments.” In my position, I was active in seeking out opportunities for these developments. I also became active in working on the legislation that became The Fair Housing Act in 1985 that moved responsibility for the affordable housing doctrine from the courts to the Council on Affordable Housing (COAH). In 1993, I was appointed by Governor James Florio to COAH, where I served until 2004. I was very involved in the nitty gritty of the Second Round Rules of COAH, but when the time came for the rules to be updated, Governor Jim McGreevey and his cabinet wanted to shift the Rules into a “growth share” model—a model that I felt did not promote affordable housing and was likely unconstitutional. I voted against the adoption and was subsequently not reappointed to COAH.Incidentally, my interpretation as to the constitutionality was ultimately proved to be correct by the New Jersey Supreme Court about 10 years later.

Q: Your work over the years helped to bridge real estate development and smart growth. Can you talk about how you did that?

A: I had been active in the New Jersey Builders Association as the representative for K. Hovnanian. I worked my way up the ladder becoming president in 1995. As president, I had a voice in helping shape the policy positions of the organization. During the 1990’s and 2000’s, the market for new housing was shifting from the traditional single-family detached housing in the suburbs to more dense, walkable places. I think my positions with K. Hovnanian and within the trade association enabled me to have a voice in the discussions shifting land use policies toward the “smart growth” approach.

Q: What has shaped your commitment to progressive land use policy?

A: In college, I was a political science major and always had a strong interest in public policy. Personally, it had never seemed right to me that so many people did not have access to decent housing, food, healthcare, etc. At the same time, there is nothing wrong with business and people making profits for what they have done. I believe that they are not mutually exclusive. Our society benefits if everyone is better off. And economically, everyone benefits if no one suffers.

Q: What can you say about your role as a New Jersey Future Trustee and the organization over the years?

A: I joined the New Jersey Future Board in 2007 as a trustee. I had known a few of the founders of the organization and was impressed with the approach to having a balance of different interests on the board including developers, environmentalists, and government and non-profit leaders. It was not very common for an organization to explicitly seek such a balance. After I retired from K. Hovnanian to become the director of the Real Estate Institute at Monmouth University and a full-time professor, I was asked to become the chair of New Jersey Future’s Board of Trustees. It has been one of my favorite and most enjoyable volunteer positions. I was fortunate to have Pete Kasabach take over as Executive Director about the same time as I joined the Board. Together, we were able to help steer the organization through the 2010’s. We were fortunate that public interest was growing in our issues of intelligent growth, smart land use policies, equity concerns, and balancing development and environmental interests.

Q: What are some highlights from your time on New Jersey Future’s Board of Trustees?

A: When Superstorm Sandy struck on October 29, 2012, Pete Kasabach and I had a phone conversation the next day as to what role New Jersey Future could take. We decided to try to put together a major forum on what New Jersey should do in the wake of Sandy to help the state rebuild and to learn from the lessons of Sandy. We were able to pull together a major conference a month later at Monmouth University with very impressive speakers from around the nation. Over 500 people attended. I think that event helped elevate the importance of New Jersey Future in the public dialogue.

The opportunity to help the organization become a leader in promoting safe drinking water has resulted in real change for so many in New Jersey. The work of Jersey Water Works in promoting solutions for water problems is having real lasting impact on this most basic and important need of the people.

I am also proud of the staff and board’s emphasis on promoting the Justice, Equity, Diversity, Inclusion initiative both within the organization and outside. Many organizations are recognizing that need and I think New Jersey Future is setting an excellent example in that regard.

Our two major events, the annual Redevelopment Forum and the Smart Growth Awards, are now viewed as very important programs and bring together many hundreds of interested people and recognize well-planned projects that might otherwise not receive public accolades. Getting a Smart Growth Award from New Jersey Future is now considered quite an achievement and is widely promoted by the award winners.

I am very proud of the staff and trustees for continuing to maintain the balance of interests within New Jersey Future that the founders created. In analyzing a potential position on an issue, New Jersey Future continues to insist on principled decision making and analysis without succumbing to partisan or other interests not consistent with our mission. I think New Jersey Future is held in high esteem by policy makers for this approach and consistency.

Q:Is there anything you would like to add?

A: It has been one of my great honors to be involved with New Jersey Future. The members of the board are all highly recognized within their sphere and all bring a commitment to making New Jersey a much better place in the future. I come away from every meeting or event fully energized from the intellect and energy demonstrated.

The primary mission of New Jersey Future has evolved over its more than thirty year history from promoting the State Plan to promoting policies that create a strong, diverse and fair state. But the vision of a strong future for the state has not changed. The dedication of the trustees and staff throughout have proved the original idea to be correct. I am confident that New Jersey Future will continue to be a leading voice for promoting a strong, fair, equitable, diverse state into the future for many years.

To Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions, We Need to Drive Less—and Build Smarter

October 14th, 2020 by Tim Evans

We are not going to meet our greenhouse gas reduction goals through electric vehicles alone; we need to find ways to allow people to drive less. A new report from Transportation for America, Driving Down Emissions: Transportation, Land Use, and Climate Change, makes clear that the amount of carbon we pump into the atmosphere still depends on how much we drive, which in turn depends on where and how we build things.

We are not going to meet our greenhouse gas reduction goals through electric vehicles alone; we need to find ways to allow people to drive less. A new report from Transportation for America, Driving Down Emissions: Transportation, Land Use, and Climate Change, makes clear that the amount of carbon we pump into the atmosphere still depends on how much we drive, which in turn depends on where and how we build things.

The report reminds us that the amount of driving people do is not an immutable background condition that we must simply factor into other calculations. Rather, travel behavior is a direct result of signals sent by the public sector about how people are expected to travel. Federal and state government policies that favor car travel over other modes of transportation, and that prize mobility (increasing vehicle speed) over accessibility (reducing trip distances by bringing destinations closer together), induce people to drive more and to walk, bike, or ride public transit less. The focus on vehicle throughput manifests itself in road design that treats pedestrians as an afterthought (at best) and makes walking unsafe in too many places.

Travel behavior is also influenced by local government land-use decisions that place different kinds of destinations far apart from each other, through single-use, low-density zoning, and branching street networks that funnel traffic onto a few high-speed arterial roads, even for local trips. Never mind that the state’s existing mixed-use, walkable communities with traditional downtowns, grid street networks, and a variety of housing types have accounted for most of New Jersey’s population growth over the last decade; building more of this kind of development would not pass muster with the zoning code in most places today. The Transportation For America report points out that “We can make a significant dent in the growth of emissions simply by satisfying the pent-up market demand for affordable homes in the kinds of walkable, connected communities where residents drive far less each day than their counterparts in more sprawling locations.” Putting more homes, stores, and offices in places where people can walk (or take shorter car trips) is a win-win.

This is especially true for lower-income households who would prefer not to incur the expense of driving everywhere (let alone purchasing an electric vehicle) but who cannot afford the high price of entry into many walkable towns, thanks to zoning that restricts the supply of housing, pushing prices upward. Electrifying the vehicle fleet would, on its own, do nothing to address these problems.

If we want a more equitable solution to greenhouse gas emissions—and want to help solve the lack of supply and diversity of housing options at the same time—we need to make reducing vehicle-miles traveled an explicit goal of the transportation system and remind transportation officials that, ultimately, it’s people—not cars—that need to get from one place to another. We need to be mindful that there are plenty of households whose difficulties with the current transportation system will not be solved simply by electrifying all our cars and trucks. We need to invest in our public transportation system and to make walking and biking safer, so more people have options beyond driving. And we need to confront the system of local land-use rules that make low-density, single-family detached housing and car-dependent commercial strips the default development pattern and instead make it easier to accommodate new population and job growth in the kinds of compact, walkable centers that people already desire.

Changes to Municipal Land Use Law would make NJ municipalities more resilient

October 14th, 2020 by Missy Rebovich

Almost every year for the past two decades, New Jersey has experienced a presidential-declared disaster in some location along the coast while many New Jersey towns experience chronic flooding as a result of increasingly severe storms. These events are expected to grow worse as climate change continues to warm our atmosphere. As sea levels rise and flooding intensifies, the economic impact of each storm increases, and is felt by everyone. Residents seek to rebuild homes, businesses have to deal with ruined inventory and try to stay afloat when shops are flooded or destroyed, and commuters must navigate roads that are flooded or attempt to use transit that is inoperable in order to access basic necessities.

Climate-related hazards will only become more frequent and more damaging over time, so preparations and planning must start now. Currently, New Jersey’s Municipal Land Use Law does not account for climate change, but a bill sponsored by Senator Bob Smith (S2607) and Assemblywoman Nancy Pinkin (A2785) would require the land use plan element of municipal master plans assess likely impacts associated with climate change-related risks and devise strategies to address them. This type of forward-thinking land use planning is critical to keeping New Jerseys residents, businesses, and the environment safe and thriving.

The bill has cleared the Senate and made it through the Assembly Environment and Energy Committee. New Jersey Future hopes to see this legislation pass through the Assembly and signed into law so our cities and towns can start planning for a more resilient tomorrow. To support the bill, email Assembly Speaker Craig Coughlin (asmcoughlin njleg

njleg org) and ask him to post the bill for Assembly vote.

org) and ask him to post the bill for Assembly vote.

The Geography of Poverty and Race in New Jersey

October 14th, 2020 by New Jersey Future staff

Despite New Jersey’s urban resurgence in the years since the Great Recession, and despite concerns about gentrification expressed in popular media, high-poverty neighborhoods have not gone away. Inspired by a study earlier this year by the Economic Innovation Group (EIG) that documented how concentrated poverty has continued to spread in the United States, New Jersey Future has performed a similar analysis of poverty in New Jersey over the last two decades, including an analysis of how the demographics of high-poverty neighborhoods have changed. Like the EIG study, we used census tracts to represent the concept of a neighborhood, and we defined “high-poverty” as having a poverty rate of 30% or higher.

Despite New Jersey’s urban resurgence in the years since the Great Recession, and despite concerns about gentrification expressed in popular media, high-poverty neighborhoods have not gone away. Inspired by a study earlier this year by the Economic Innovation Group (EIG) that documented how concentrated poverty has continued to spread in the United States, New Jersey Future has performed a similar analysis of poverty in New Jersey over the last two decades, including an analysis of how the demographics of high-poverty neighborhoods have changed. Like the EIG study, we used census tracts to represent the concept of a neighborhood, and we defined “high-poverty” as having a poverty rate of 30% or higher.

Concentrated poverty has been on the rise in New Jersey in the last two decades, as is true nationally. In 2000, New Jersey had 110 high-poverty neighborhoods, representing 5.7% of all tracts in the state.1 In 2012, there were 134, or 6.7% of all tracts. By 2018, that number had risen to 145, or 7.2% of the total number of neighborhoods in the Garden State. It is true that some neighborhoods have transitioned out of poverty—45 census tracts exceeded a 30% poverty rate in 2012 but not in 2018.2 These are often found in places we think of as revitalizing urban centers, including Jersey City, Newark, East Orange, Elizabeth, Trenton, Perth Amboy, Asbury Park, Camden, and Millville. But they are outnumbered by neighborhoods that have transitioned into high poverty between 2012 and 2018, of which there are 56. It is very often the case that new high-poverty neighborhoods occur in different parts of the same cities in which other neighborhoods are transitioning out of poverty, a reminder that poverty is still a growing problem even in cities where “gentrifying” neighborhoods grab most of the headlines.

The overall story, however, is one of persistent poverty. From 2012 to 2018, 89 neighborhoods started out high-poverty and stayed that way. And not only are high-poverty neighborhoods a persistent problem, they also continue to be racially segregated. Majority-Black neighborhoods are much more likely to have poverty rates above 30% than is true statewide, with 33.2% of majority-Black neighborhoods also qualifying as high-poverty, compared to only 7.2% of all tracts. Similarly, 23.9% of majority-Hispanic neighborhoods are also high-poverty. Of all 145 high-poverty neighborhoods in the state in 2018, 42.8% were majority-Black and 35.9% were majority-Hispanic, while the total state population is only 12.7% Black (non-Hispanic) and 19.9% Hispanic.

With the percent of all neighborhoods having poverty rates of 30% or more gradually increasing, and with the percentages of majority-Black and majority-Hispanic neighborhoods that are also high-poverty both much higher than the statewide rate and growing faster, it is clear that poverty—and especially racially segregated poverty—is very much still with us and getting worse.

See the full report for more detailed information.

1 The total number of census tracts in the state was 1,944 in 2000, rising to 2,010 after the 2010 Census, as population increased and new tracts were defined.

2 Tract boundaries are redefined for each decennial Census, so 2000 Census tracts cannot be directly compared to post-2010 data in many cases, limiting trend analysis for individual tracts.

New Jersey Future Partners with the New Jersey District of Key Club International

October 14th, 2020 by New Jersey Future staff

New Jersey Future is excited to announce a new partnership with the New Jersey District of Key Club International and the District Project Steering Committee for the group’s service year project “Keeping the Garden State Green.”

The New Jersey Key Club District reviewed environmental organizations around the world and selected New Jersey Future as one of three partner organizations for its environment-driven project. Key Club is an international, student-led organization that provides its members with opportunities to perform service, build character, and develop leadership. In New Jersey, there are over 140 high school Key Clubs, with over 12,000 student members.

During the 2020-2021 academic service year, all Key Club members in New Jersey will be supporting service projects related to the District’s “Keeping the Garden State Green” initiative. Students from every county in the state will focus on projects and events related to environmental awareness and education, devoting substantial time and effort to supporting the well-being of the planet and making a positive impact on the environment.

The New Jersey Key Club held a virtual student rally on Sunday, October 11 to kick off the new service year and District project. As a partner organization, New Jersey Future was invited to participate, and created a video shown during the rally about our work to mainstream green infrastructure, featuring Stormwater Director Kandyce Perry and Policy and Program Coordinator Andrew Tabas.

The educational video teaches about the problems of stormwater runoff, which has been greatly exacerbated in our region as heavy rain events have increased by more than 70%in the last 50 years. The video explains the benefits of using green infrastructure to manage stormwater and provides examples of specific actions students can take to help address stormwater problems in their communities, such as installing rain barrels and rain gardens at their homes and schools.

The educational video teaches about the problems of stormwater runoff, which has been greatly exacerbated in our region as heavy rain events have increased by more than 70%in the last 50 years. The video explains the benefits of using green infrastructure to manage stormwater and provides examples of specific actions students can take to help address stormwater problems in their communities, such as installing rain barrels and rain gardens at their homes and schools.

New Jersey Future is looking forward to working with the New Jersey Key Club this year in its efforts to keep New Jersey green. We’ve asked these young environmental leaders to tell us their stories about working with green infrastructure as part of their service project this year and we are looking forward to sharing them with you. Stay tuned!

Broadband for All: The Geography of Digital Equity in New Jersey

September 16th, 2020 by Kimberley Irby

Today, the internet is the medium through which people access healthcare, housing, employment, safety, and education. Access to the internet is an essential public good, as much as access to clean water, energy and transportation. Recent Census Bureau estimates indicate that 16-17% of households (about half a million) in New Jersey lack internet access. For New Jersey’s recovery from the pandemic to be successful, everyone should have the ability to access the internet at reasonable speeds with affordable prices regardless of their geography or income.

Extent of the digital divide in New Jersey

Before the pandemic necessitated many to work or learn from home, the digital divide throughout the country was apparent in terms of geography, class, and race. In 2018, NJ Spotlight published an interactive map, featuring American Community Survey (ACS) 2013-2017 estimates, that revealed access issues in low-income urban and rural areas in New Jersey, similar to the rest of the nation. According to the data, people in fewer than 60 percent of households could go online in the cities of Perth Amboy, Salem, Bridgeton, Camden, and Trenton, whereas at least 95 percent of households had internet access in 17 wealthier communities in the north or central parts of the state. It is important to note that ACS data only provides estimates and current Federal Communications Commission (FCC) data conveys significant overestimates of internet coverage. To truly close the divide and achieve digital equity, it is important that we have the most up-to-date and accurate data possible.

What we can do about the digital divide in New Jersey

BroadbandNow claims that the two most effective ways state and local governments can improve their broadband situation are by: 1) creating better mapping and adopting smarter funding strategies and 2) promoting and encouraging community broadband solutions in low-competition areas. BroadbandNow further claims that both of these methods are at odds with the actions of dominant Internet Service Providers (ISPs) that have contributed to inflated measurements of internet speeds and competition at the federal level and fought against municipal broadband. Thus, it is critical to first understand where and what type of coverage is available in New Jersey. An effective way to do this is through a statewide broadband office, which can not only collect data, but also communicate, coordinate, plan, and fund. Although COVID-19 is resulting in slashed state budgets, we can still look to examples like New York, Minnesota, Illinois, and Georgia, for inspiration and guidance.

Community or municipal broadband refers to broadband internet access services that are provided either fully or partially by local governments. The benefit of municipal broadband, when done well, is that it provides high-speed internet with rates that are competitive with those of national ISPs. To date, no municipal networks exist in the state, but there is pending legislation (Assembly Bill A850) to create a “Community Broadband Study Commission” that would evaluate the feasibility of establishing community broadband networks. Public-private partnerships are another popular alternative for expanding access. In fact, some types of municipal broadband are achieved through these partnerships. In March 2020, another Assembly bill (A3649) was introduced that would require the Office of Information and Technology (OIT) to establish a statewide wireless network through a public-private partnership agreement, in which the private entity would assume responsibility for construction and cover some or all of the up-front costs.

The future of the digital divide in New Jersey

Currently, other organizations in the region are working to assess the situation in more depth and recommend specific policies to enact. For example, the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission is conducting a three-part study on broadband deployment and access throughout the Greater Philadelphia area. The first part, Discussing Technology, outlines broadband basics and deployment throughout the region. The upcoming second part, Understanding the Digital Divide, will cover the extent of the digital divide at the neighborhood level as well as its ramifications during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the third part, Bridging the Digital Divide, will feature policy recommendations.

From the data we currently have, despite the lack of precision, we know that New Jersey is one of the most highly wired states, if not the highest, in the nation. Thus, it’s within our reach to become the first state to actually achieve full broadband coverage. Given how critical internet access is to quality of life and equitable, inclusive communities, closing the digital divide should be a priority for New Jersey as it recovers from the economic damage of the pandemic. If our government commits to obtaining updated data and exploring solutions for the communities most in need, we can cement our status as a broadband leader and prove that digital equity is integral to New Jersey’s future.

See the full analysis here.