New Jersey Future Blog

New Stormwater Rules Require New Developments to Include Green Infrastructure

March 5th, 2021 by Kandyce Perry

Stormwater runoff is a serious problem, made increasingly worse by climate change. Stormwater causes flooding and pollutes the streams, rivers, and lakes that provide drinking water and places for recreation. By most estimates, over 90% of New Jersey’s waterways are polluted, much of which is due to stormwater runoff. To better address stormwater runoff issues, new public and private sector developments in New Jersey must now include the use of green infrastructure as a stormwater management technique starting March 2, 2021 as a result of the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection’s (NJDEP) newly amended Stormwater Management Rules (NJAC 7:8).

“These new rules demonstrate the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection’s commitment to improving water quality and reducing flood risk by prioritizing green infrastructure. Across the country, there are robust municipal stormwater programs that deliver compelling environmental, economic, and societal results locally. New Jersey’s rule change provides a national example of a statewide stormwater approach with buy-in from the environmental and development communities,” said New Jersey Future Executive Director Peter Kasabach.

This rule change requiring public and private developments to include green infrastructure—a set of stormwater management practices that use or mimic the natural water cycle to capture, filter, absorb, and/or reuse stormwater—is the result of a paradigm shift in New Jersey stormwater management. The new rules replace a subjective performance standard asking developments to use green strategies to sustainably manage stormwater to the “maximum extent practicable” with an objective and mathematically-based requirement for green infrastructure practices to be distributed around a site rather than centralized in one oversized basin. Distributed green infrastructure enhances the reliability and effectiveness of stormwater management and maximizes developable area on a site, and developers will now receive credit for its use toward their stormwater management requirements.

The rule change provides objectivity and predictability in the stormwater review process, saving developers time and money. “Our customers and our neighbors want to see green infrastructure. The market is demanding it. And that, combined with predictability, is what aligns this new green infrastructure requirement with our bottom line. We know it will be good for the environment, and we believe it’ll be good for business, too,” said George Vallone, president of Hoboken Brownstone Company, 2015 president New Jersey Builders Association (NJBA), and co-chair of New Jersey Future and NJBA’s joint Developers Green Infrastructure Task Force with Peter Kasabach.

“We recognize the new requirements will require learning and adaptation by municipalities, developers, and their engineers who are less familiar with green infrastructure. New Jersey Future’s stormwater tools are helping these groups take advantage of the opportunity to improve the quality of life for residents and clients and maximize returns on investments. In many cases, green infrastructure costs less than grey infrastructure or is cost-neutral when managing the same amount of runoff,” said New Jersey Future Director of Stormwater Kandyce Perry.

While the newly amended rule does not change underlying requirements for water quality, it will result in more stormwater soaking into the earth instead of running off from new developments. However, more can and should be done to prevent pollution, reduce flooding, and get ahead of climate change. New Jersey Future looks forward to working with NJDEP and other stakeholders to formulate additional rule changes aimed at strengthening standards for water quality and stormwater volume control and addressing how redeveloped sites manage stormwater.

New Jersey Future has three resources to help municipalities and developers learn more about green infrastructure and the newly amended rules:

Green Infrastructure Municipal Toolkit: One-stop green infrastructure resource designed to help municipal leaders and advocates address the related problems of nuisance flooding and polluted waterways. The toolkit includes detailed information and a variety of tools that cities and towns can use to plan, implement, and sustain green infrastructure in public- and private-sector development projects.

Enhanced Model Stormwater Ordinance for Municipalities: Municipal stormwater ordinances enact the state’s stormwater rules at the local level. Municipalities may adopt stormwater ordinances that are stronger than the state’s minimum requirements to further increase green infrastructure and reduce flood risk. This tool provides guidance for municipalities who are determining how they should enhance their ordinance and includes a side-by-side table to compare NJDEP’s requirements and New Jersey Future’s recommended enhancements.

Developers Green Infrastructure Guide 2.0: Practical guide that breaks down New Jersey’s Stormwater Rule amendments and helps developers and decision-makers understand green infrastructure options (even for challenging sites), advantages, costs, and benefits.

To learn more, visit New Jersey Future’s Mainstreaming Green Infrastructure program aimed at making green infrastructure the first choice for stormwater management in New Jersey.

Where Do New Jersey’s Property Tax Bills Hit the Hardest?

February 15th, 2021 by Tim Evans

Recently-released property tax data from the Department of Community Affairs have reminded us once again that New Jerseyans pay a lot in property taxes. Indeed, New Jersey residents pay the highest property tax bills in the country—a median of $8,432 as of the 2019 American Community Survey1. No other state comes close; second-place Connecticut’s median real estate tax bill is $6,004, more than 25% lower than New Jersey’s. In general, the other states near the top of the list (New Hampshire, New York, and Massachusetts round out the top 5) are other Northeastern states that are heavily reliant on property taxes for generating government revenue.

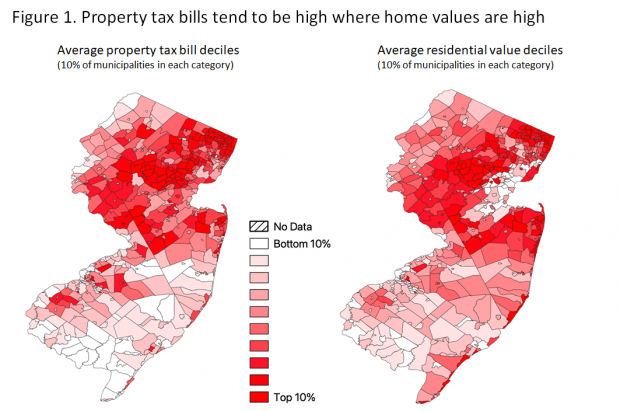

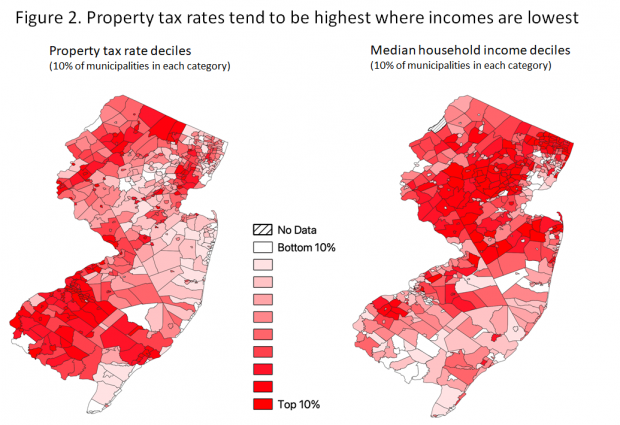

It’s Not the Size of the Bill

Most media coverage tends to misdiagnose where property taxes inflict the most pain, focusing on the absolute amount of the bill. Property tax bills, unsurprisingly, tend to be highest where property values are highest (see Figure 1). Among the top 10 municipalities with the highest average tax bills—Tavistock, Millburn, Mountain Lakes, Tenafly, Demarest, Glen Ridge, Rumson, Alpine, Essex Fells, and Princeton—all have average residential values of more than $600,000 (compared to the statewide average of $330,578), and in half of them the average home value is more than $1 million. Four of them2 are also in the top 10 municipalities with the highest median household incomes. Property tax bills are high in communities with high property wealth because such places value high-quality government services and are willing and able to pay for them. High property tax bills that result from high home values thus do not necessarily constitute a problem.

High Values, Low Rates

The picture changes with a different perspective on what it means to pay “a lot” for property taxes. Specifically, where are property tax rates the highest? Not in the places with the biggest average tax bills, or the places with the most expensive homes. Among the 50 municipalities with the highest average tax bills, the median property tax rate is 2.163%, compared to a median rate of 2.614% over all other municipalities. Of the 50 municipalities with the highest average home values, more than half (26) are among the bottom 50 with the lowest tax rates. When a town’s homes are expensive, it doesn’t have to tax at a very high rate to raise a lot of money to pay for government services.

Highest Rates in Low Income Communities

Instead, high property tax rates are found most consistently among municipalities where incomes are lower. The list of the 10 municipalities3 with the highest tax rates—Woodlynne, Salem, Penns Grove, Hi-Nella, Trenton, Egg Harbor City, Pleasantville, Irvington, Lindenwold, and Laurel Springs—differs dramatically from the earlier list where the tax bills are highest (and where tax rates tend to be among the lowest). All but one of these places rank in the bottom 50 municipalities with the lowest median household incomes, and four of them have median incomes that are less than half the statewide median. Among the 50 municipalities with the lowest median household incomes (all less than $57,000, compared to a statewide median of $82,545), the median tax rate is 3.185%, substantially higher than the median of 2.523 percent over the rest of the state’s municipalities. The places with high property tax rates—where property tax bills take a bigger bite, proportionally speaking—are not, by and large, wealthy places.

New Jersey does indeed have a property tax problem, but it’s a much bigger problem for low-wealth communities than for wealthy ones. In the mostly lower-income places where tax rates are highest, property taxes place a huge burden on the households and businesses that are located there and discourage new residents and businesses from moving in. Similarly, it makes it more difficult to jumpstart new redevelopment and revitalization efforts since the newly constructed projects will carry an outsized property tax bill. These places ought to be part of the discussion and are the places on which any effort at tax reform should be focused.

1 Data from the American Community Survey are derived from a sample, so values will not match up precisely with data from the NJ Department of Community Affairs, which collects full property tax data from every municipal government in the state. The ACS is useful for comparing states to one another, however.

2 For confidentiality reasons, the Census Bureau does not publish median household income data for Tavistock, which has a total population of only 5 people.

3Excluding Winfield and Audubon Park, where historical non-standard homeownership models make statistics on home values and tax rates not directly comparable to other municipalities.

Helping towns design for all ages: New Jersey Future’s aging-friendly program is gaining momentum

February 15th, 2021 by Tanya Rohrbach

Despite the challenges of 2020, several towns followed through on their commitments toward creating great places to age. They recognize that addressing the health needs of older residents includes making sure the built environment supports the ability of older residents to choose safe, suitable housing options and to easily get around town, whether for accessing daily needs and services or for getting exercise or averting isolation. The impacts of COVID-19 on the older population has made the need for intentional aging-friendly community design more apparent than ever. An aging-friendly community design model is based on the livability of a community and includes access to: housing, transportation, mobility, public and open spaces, social interaction, health and wellness services, and other community elements.

Here’s a summary of milestones recently achieved by a number of towns New Jersey Future is working with to implement aging-friendly land use goals.

- The Borough of Pompton Lakes, Passaic County, engaged in a planning process to complete an aging-friendly land use assessment for the borough. The land-use assessment identified key steps the borough can take to facilitate a more aging-friendly environment such as permitting other housing types in single-family detached zones, improving pedestrian and bicycle access to destinations, and zoning changes to promote more compact mixed-use development in the downtown area. Pompton Lakes is actively seeking redevelopment opportunities, and the aging-friendly land use assessment will assist the Borough in using an aging-friendly lens to ensure the community grows in a way that benefits all residents.

- The Village of Ridgefield Park, Bergen County, also worked through a planning process with New Jersey Future to develop an aging-friendly land use assessment for the village. The land use assessment identified aging-friendly components the village can incorporate into its master plan update, including the creation of public spaces for social interaction and activation in the downtown, an increase in smaller, centrally-located housing units suitable for older residents, specific improvements to the pedestrian environment, and access to the waterfront.

- The Borough of Fair Lawn, Bergen County, worked with New Jersey Future to create an action plan to implement aging-friendly land use strategies. Fair Lawn is also engaged in redevelopment efforts and aims to ensure community changes are in line with aging-friendly principles. The action plan provides specific things the borough can do to integrate aging-friendly decision-making into municipal land use planning, policies, and regulations.

- The Village of Ridgewood, Bergen County, participated in a thorough implementation planning process to develop a detailed implementation plan that outlines specific actions to implement priority aging-friendly objectives. The goals the village identified in the planning process include, improving pedestrian safety and mobility, expanding housing diversity and affordability, creating a more vibrant and mixed-use downtown, and aligning the master plan with aging-friendly community design goals. Ridgewood, along with all the towns New Jersey Future worked with, also aims to engage residents in meaningful and effective aging-friendly community building initiatives.

In November 2020, New Jersey Future published Creating Great Places to Age: A Community Guide to Implementing Aging Friendly Land Use Decisions to provide step-by-step guidance for any town or advocate endeavoring to create a more aging-friendly community. The guide contains detailed descriptions of New Jersey Future’s process: from education and community building to conducting a land-use assessment to implementation. It contains a plethora of links and resources for any community to work through the process or learn more about aging-friendly communities or land use planning.

To demonstrate ways towns are actively trying to meet the housing needs of older residents throughout the state, New Jersey Future produced a report highlighting case studies of municipal strategies to diversify housing stock for an aging population. Case studies in the report describe how five municipalities throughout New Jersey have each implemented a strategy, providing a roadmap for other local governments or advocates. Case study strategies include a public-private partnership or changes to zoning to allow for accessory dwelling units, promoting transit-oriented development, or adopting a form-based code. Although the list is not inclusive of all strategies implemented by all New Jersey municipalities, it demonstrates that towns are capable of implementing a variety of strategies in a variety of ways that are suitable to their needs.

Moving forward, New Jersey Future will put a particular focus on dismantling barriers so that community members historically left out of the planning, decision-making, and benefits concerning their built environments can engage in this expanding initiative. Good community design can only be achieved when disparities are addressed head-on. This is a guiding principle for New Jersey Future as we continue to engage communities in becoming better places for people to live as they age.

Continuing Implications of Broadband Inequity

February 11th, 2021 by Kimberley Irby

In September of last year, we described the state of broadband access in New Jersey and stated that “for [our] recovery from the pandemic to be successful, everyone should have the ability to access the internet at reasonable speeds with affordable prices regardless of their geography or income.” We noted that inequitable broadband access, which contributes to a variety of inequitable outcomes, is an infrastructure issue that must be addressed to achieve New Jersey Future’s mission of strong, healthy, resilient communities for everyone. Now, as we move closer to a full recovery with the rollout of vaccines, we must not lose focus on the issues surrounding broadband access that can hinder our progress towards a “new normal.”

Soon after COVID-19 caused many to shelter in place in March 2020, unequal internet access was featured in discussions about existing inequities underscored by the pandemic. Now, the issue is in the spotlight again as the rollout of vaccines gains steam. Just a few months into the distribution of two major COVID-19 vaccines, we are already seeing racial disparities in vaccinations nationwide and in New Jersey, and one contributing factor is the digital divide. Without access to the internet, it can be much harder to obtain information about where and when to get a vaccine as well as make an appointment for one, as sign-ups are being largely coordinated online. This issue is also impacting seniors, a group that is prioritized to get vaccinated as soon as possible. In a call to close the digital divide in order to vaccinate the country, Dr. Ranit Mishori notes, “When it comes to vaccine distribution, [those who have trouble accessing the relevant websites] are all shut out of opportunities to access a vaccine that can literally save their lives.” In the short-term, efforts will have to be made through low-tech means to overcome these hurdles, but this serves as yet another stark reminder of the great investments needed over the long-term to eliminate broadband inequity, which can ultimately help achieve broader health equity.

In addition to health, education has been the focus of unequal internet access throughout the course of the pandemic. As of early February 2021, roughly 400 New Jersey students are still in need of devices or internet access, down from 231,000 that were in need at the beginning of the school year. Though significant progress has been made, there are still challenges related to remote learning and certain districts have been disproportionately impacted. As schools gradually begin to reopen, administrations will have to address mistrust among Black families, persisting even as their children suffer from remote learning, which is due in part to inadequate internet access. Additionally, though younger students have been the focus of work to close the digital divide, many college students that were reliant on school computers and Wi-Fi to complete their studies are also struggling. Even once the pandemic is a thing of the past, some schools, at every level of education, will likely keep some degree of remote learning, so the permanent erasure of the digital divide must continue to be a priority even as students are able to gather in classrooms more regularly.

Now that the Biden administration is in office, we can expect to see increased federal efforts through its plans to expand rural broadband, municipally-owned networks, and telehealth, as well as facilitate the ongoing process to improve FCC broadband maps. At the state level, New Jersey has made progress on closing the digital divide for K-12 students, and the state Senate has recently approved legislation to form a commission that would assess the feasibility of community broadband networks and report on its findings within a year. It is exciting to consider the potential momentum for broadband support at the federal level, which will hopefully be coordinated with state and local efforts to ultimately provide equitable access to broadband both in New Jersey and nationwide as we “build back better” from the pandemic.

Older Homeowners in Car-Dependent Suburbs Face Difficulty Downsizing

February 11th, 2021 by Tim Evans

Arthur Nelson at the University of Arizona recently released a study, “The Great Senior Short Sale,” describing the mismatch between retiring Baby Boomers seeking to sell their mostly single-family detached homes on large lots and younger homebuyers who are mostly looking for other housing options. The study predicts that “many baby boomers and members of Generation X will struggle to sell their homes as they become empty nesters and singles,” because young homebuyers don’t want what they are selling.

Arthur Nelson at the University of Arizona recently released a study, “The Great Senior Short Sale,” describing the mismatch between retiring Baby Boomers seeking to sell their mostly single-family detached homes on large lots and younger homebuyers who are mostly looking for other housing options. The study predicts that “many baby boomers and members of Generation X will struggle to sell their homes as they become empty nesters and singles,” because young homebuyers don’t want what they are selling.

New Jersey Future has called attention to a similar predicament facing older residents in our 2014 report Creating Places To Age in New Jersey, which noted that there were hundreds of thousands of people “aging in place” in places that were designed for travel almost exclusively by automobile, creating a looming mobility problem for older people who may soon be looking to scale back their driving—or may be forced to give it up altogether. And we have noted (in our 2017 report Where Are We Going? Implications of Recent Demographic Trends in New Jersey) that Millennials are drawn to compact, walkable towns where they don’t need a car every time they leave home and are hence unlikely to represent a strong market of buyers for the Boomers’ suburban homes in car-dependent neighborhoods.

Seven years later, this problem has gotten more urgent. As of the 2018 five-year American Community Survey, there are about 700,000 New Jersey residents age 65 or older who are living in municipalities that score poorly on measures of compactness and walkability that New Jersey Future uses to identify aging-friendly towns. And the wave hasn’t crested yet, with the younger half of the Baby Boom generation still to hit retirement age. Many of these aging homeowners will face difficulty downsizing within their existing community, since the state’s more car-dependent places also tend to offer few options beyond single-family detached homes.

Read the full report for details, and for recommendations for what communities of different types can do to make themselves more aging-friendly.

New Jersey Future and other Jersey Water Works Members Call for Federal Funding for Water Infrastructure

February 10th, 2021 by Missy Rebovich

New Jersey Future joined 56 Jersey Water Works members calling for federal investment in our water infrastructure in a letter sent to New Jersey’s congressional delegation.

New Jersey’s communities continue to confront issues including aging infrastructure, lead in drinking water, combined sewer overflows, and polluted waterways. With the added burden of the COVID-19 economy, the funds needed for these infrastructure investments exceeds the resources available to local and state governments, making a federal infrastructure investment essential.

The letter details five steps the federal government can take to ensure safe, clean drinking water for every New Jerseyan, including:

- Increasing the Drinking Water and Clean Water State Revolving Funds (SRF) to $14 billion and $13 billion, respectively, as well as revising limits on principal forgiveness.

- Introduce a House companion to the Drinking Water Infrastructure Act of 2020 (pending in the US Senate) to facilitate replacement of toxic lead service lines.

- Create a federal water affordability program to provide financial and water efficiency assistance to low-income customers, as suggested by the EPA’s National Drinking Water Advisory Council’s Affordability Work Group in 2009.

- Advance climate solutions drawn from the Blueprint to Rebuild America’s Infrastructure as well as the Water Infrastructure Act (WIA) of 2020 and the Drinking Water Infrastructure Act (DWIA) of 2020, that include solutions for small, financially disadvantaged, and rural communities.

- Develop a new COVID-19 recovery package that targets significant new investments in community development programs that address long-standing and unjust environmental, health, and economic burdens, specifically Community Development Financial Institutions, Community Development Block Grants, the Environmental Protection Agency’s Brownfields Program, expanded funding for federally qualified health centers, and Environmental Justice Small Grants Program.

Read the full letter here.

Want to Get Ahead of Flooding? Use NJF’s New Tool, the Enhanced Model Stormwater Ordinance

February 9th, 2021 by Andrew Tabas

Stormy days ahead call for strong municipal stormwater ordinances. Climate change is bringing increased rainfall and flooding to New Jersey which, if ignored, will damage property, threaten public health, and pollute waterways. Municipal governments’ responses to this challenge will define the quality of life in their towns for generations. Fortunately, municipalities have a strong device to promote responsible and resilient development: stormwater ordinances. The stormwater ordinance is key to implementing public and private green infrastructure, a group of practices that mimic the natural water cycle to capture rainwater where it falls. Municipal leaders should use New Jersey Future’s new tool to update their town’s stormwater ordinance as soon as possible to increase green infrastructure and reduce flood risk.

To prevent flooding in the face of increased rainfall from climate change, municipal leaders should use NJF’s Enhanced Model Stormwater Ordinance to develop their local stormwater ordinance.

With the state’s most recent amendments (effective March 2) now requiring stormwater to be managed with green infrastructure (GI), each municipality can decide how best to bring the benefits of GI to their communities with an enhanced ordinance that is stronger than the state’s minimum requirements.

To help municipalities make choices about how to adopt a stronger stormwater ordinance, New Jersey Future developed a new tool, the Enhanced Model Stormwater Ordinance for Municipalities, also available as an editable Word document. It compares and recommends several options for improvements to the minimum requirements in NJDEP’s example stormwater ordinance. While NJDEP’s requirements represent a paradigm shift in stormwater management, municipalities that want to get ahead of flooding and climate change, improve water quality in local waterways, and encourage developers to use more GI in their projects should consider going further. Municipalities can use their stormwater ordinance to partner with developers of both public and private projects to build GI, multiplying its benefits.

Green infrastructure, like this bioswale in Somerset, New Jersey, captures rainwater and reduces flood risk. Towns can use their stormwater ordinances to require green infrastructure. Source: Maser Consulting, 2020.

This new tool—a menu of options for towns—offers several ways for municipalities to go above and beyond DEP’s requirements, including:

- Redefine the threshold for “major development.” Reducing the threshold to trigger management of stormwater for major developments will include more development projects, capturing more stormwater. Towns that are more dense may wish to use even smaller thresholds.

- Add a definition and requirements for “minor development.” This will require additional, smaller sites to use GI. The requirements for minor development are less stringent than the requirements for major development.

- Require stormwater management on existing impervious surfaces, not just new. To add a requirement for GI in redevelopment projects, municipalities can expand the definition of “regulated impervious surface” to include “all impervious surface within the project area” instead of the “net increase of impervious surface.” Regulating existing impervious surfaces includes redevelopment sites, which will address longstanding runoff issues from existing development. Not taking this step will allow historical polluted runoff to continue to exist.

- Require infiltration of a specific volume of stormwater onsite. Requiring the infiltration of a specific volume of stormwater will increase the amount of clean stormwater returned to the ground and reduce runoff. Decreased runoff will lower the flood risk from frequent, small storms.

- Reduce “maximum contributory drainage areas.” Each GI best management practice (BMP), such as a rain garden or pervious pavement, is designed to receive stormwater runoff from a specified area. Reducing the drainage area for each BMP will prevent the BMPs from becoming overloaded and will increase the number of BMPs used in each development.

Understanding New Jersey’s rules and requirements and the opportunities for going above and beyond can help municipal leaders to build a safe, healthy, and resilient town. Photo credit: Andrew Tabas.

Understanding New Jersey’s rules and requirements and the opportunities for going above and beyond can help municipal leaders to build a safe, healthy, and resilient town. Photo credit: Andrew Tabas.

Ordinance enhancements in 2021 will dovetail with NJDEP’s plan for future regulatory amendments to address climate change later this year. By writing their updated stormwater ordinances with purpose, local leaders can put their towns on the path to managing flood risk and to being greener, more attractive, and safer places. For additional information on how to implement GI, municipal leaders should consult the Green Infrastructure Municipal Toolkit and the Developers Green Infrastructure Guide. The result of these efforts by each town in New Jersey will be a thriving state whose streets are tree-lined, whose waterways are clean, and whose people are happy and healthy.

For questions about New Jersey Future’s Enhanced Model Stormwater Ordinance for Municipalities, contact Kandyce Perry (kperry njfuture

njfuture org) .

org) .

New Jersey Future Releases Guide to Implementing Aging-Friendly Land Use Decisions

January 15th, 2021 by Tanya Rohrbach

New Jersey Future, with funding from The Henry and Marilyn Taub Foundation, developed Creating Great Places to Age in New Jersey: A Community Guide to Implementing Aging-Friendly Land Use Decisions to provide local communities with a step-by-step process to design their towns for the needs of older adults. The guide can be used by professionals, municipalities, or residents.

New Jersey Future, with funding from The Henry and Marilyn Taub Foundation, developed Creating Great Places to Age in New Jersey: A Community Guide to Implementing Aging-Friendly Land Use Decisions to provide local communities with a step-by-step process to design their towns for the needs of older adults. The guide can be used by professionals, municipalities, or residents.

Land use is a critical factor in a town’s livability, and especially for older residents. Including aging-friendly factors in local planning for features like affordable and diverse housing, transportation, walkability, flexible employment opportunities, and access to daily activities and socialization helps towns ensure that older residents can continue to live and thrive independently in the communities they know and love.

With an anticipated 8,000 members of the Baby Boom generation turning 65 every day for the rest of the decade, there is an increased urgency for land use planning to accommodate the growing population of older adults. For example, this demographic is at risk of social isolation and that social isolation presents serious threats to mental and physical health, and older adults face limited access to community resources when isolated. Where people live in relation to destinations and neighbors has a major effect on isolation risk. Older adults living in New Jersey, like many populations in our state, face difficulty in finding affordable and adequate housing. Access to transportation or safe mobility options can also affect the extent to which people can engage in their communities as they age. And these issues are exacerbated by race and class inequities or during a crisis like a natural disaster or a disease outbreak.

This guide provides information on how to organize an aging-friendly initiative, engage the community, develop a land use assessment for your town and, most importantly, how to implement aging-friendly land use actions. The guide also offers profiles of some of the municipalities New Jersey Future has worked with to become more aging-friendly.

While the focus of this guide is on increasing aging-friendliness, the suggested actions will benefit the entire community, making our towns not only great places to age, but making them stronger, healthier, and more equitable for everyone.

New Jersey Future analysis of the New Jersey Economic Recovery Act of 2020

December 21st, 2020 by Peter Kasabach

There is much for smart growth advocates to like in S3295/A4, the economic incentives legislation passed by the New Jersey Legislature today. The comprehensive package of programs represented in this bill recognizes that place matters and that government subsidies, when directed toward places where we want and need growth, can help achieve a New Jersey in which everyone can thrive. Additionally, virtually all of New Jersey Future’s smart growth recommendations have been incorporated into the legislation.

First and foremost, the suite of programs in this package recognizes the importance and preeminence of the State Development and Redevelopment Plan in assessing where growth should occur in the state. Most of the programs detailed in the bill would prioritize projects that take place in the designated growth areas, and in some cases the growth location is a key eligibility criteria. The additional targeting of federal Opportunity Zones and lower-income communities is another positive feature that will align investments with policy objectives.

The Community-Anchored Development program, the Main Street recovery program, and the entrepreneur zones working group are all evidence that this legislature and administration understand that place-based economic development is critical to the future of our state. Place-based economic development requires careful targeting, comprehensive planning, and a recognition that creating walkable, mixed-use, diverse, equitable places is a cornerstone of economic growth. A crucial inclusion in this bill is the allocation of funding for economic development planning grants for towns to assess their current situation and develop smart, implementable strategies for moving forward.

The state’s first historic tax credit program will help redevelop and revitalize our older downtowns and communities, and will allow smaller and mixed-use projects to participate, which oftentimes form the important fabric of these places.

The brownfields incentive program should be a good complement to the current brownfields clean-up programs at the state, and the other redevelopment incentive programs in the package. The current bill seems to be open to smaller, mixed-use, and residential projects, but the implementing regulations will determine if they can access the program in a feasible manner. Many of our older communities where we want to see growth and redevelopment have been stymied by the existence of contaminated sites and the extra costs that come with needing to clean them up. This is especially true in our environmental justice communities.

The Aspire program (successor to ERG) includes the very important aspect of mixed-income, residential development in targeted locations. This type of housing can be the necessary first step toward transforming downtowns and a precursor for future commercial redevelopment, job creation, and investment. The program also introduces the concept of an infrastructure fund, which is an essential acknowledgement that place-based economic development requires an investment in the infrastructure that surrounds development projects and makes a place attractive and functional for residents and businesses.

Both the Aspire program and the Emerge program (successor to Grow NJ) incorporate a new level of transparent reporting and third-party evaluation. Evaluating whether or not these programs are delivering the intended policy results and are advancing growth and development in the places where they will do the most good is a necessary process to ensure that the significant amount of state deferred revenue is being fully leveraged and well invested.

That the Evergreen program and fund puts the state in the role of investor and partner, rather than just grantor, is a positive. This relationship should allow more innovative and difficult projects to advance. If done well, it should also allow projects to expand their bottom line goals to improve community conditions, include racial and economic equity concerns, and promote more minority inclusion.

A few of the programs incorporate the concept of Community Benefits Agreements. This is an important step toward ensuring that projects don’t just serve the developer or owner, but also the surrounding host community and neighbors. The current language creates a seat at the table for the host municipality and the EDA. We recommend taking a step further to ensure that actual community members that are immediately affected by the project are also at the table. It would be wise to provide a small stipend to these individuals, since otherwise they will be the only people at the table not being paid.

While there is much to like in this long-awaited package, turning it into law is just the first step. The programs outlined are sound frameworks that need to be turned into streamlined, implementable programs that are accessible to a large number of stakeholders, especially those in lower income communities and communities of color. One aspect to note is the large allocation of funding for “transformative projects.” While this has its upside, an unintended consequence is reduced availability of funding for other projects, which may prevent many smaller, catalytic projects, led by smaller developers from advancing. It will also be important to see if the program incentive caps imposed by this legislation will slow growth and stall redevelopment momentum in our urban communities and downtowns where the most opportunity and need exists.

This is a very large and complicated bill that includes many details that are not yet fully researched or understood. It is the kind of bill that would have benefitted from additional time for the public and policymakers to understand the nuances and detailed parameters being imposed by the legislature. However, New Jersey Future does look forward to working with the legislature and administration to move from vision to incentivized projects on the ground.