New Jersey Future Blog

How to Reinvigorate Retail-Anchored Downtowns in a Post-Pandemic World

June 25th, 2021 by Tanya Rohrbach

Downtown economies need to reimagine retail. With empty storefronts plaguing Main Streets across the state and country, the How to Reinvigorate Retail-Anchored Downtowns in a Post-Pandemic World panel at the 2021 New Jersey Planning and Redevelopment Conference offered insight about the future of downtown retail amid a time of uncertainty. Recognizing that the pandemic rewarded retailers that were “adaptive, resourceful, and capable of reinvention,” the panel described a large-scale placemaking project in the redevelopment of key sites in downtown Westfield and offered a forward-thinking perspective for attracting and retaining retail.

“Retail today is not necessarily what you think it is,” explained Bob Zuckerman, the executive director of Downtown Westfield Corporation. Westfield is a case study in retail reinvention, made evident by businesses that include a retailer that provides 20 different selfie-stations, one that is a DIY paint bar where customers can create their own home decor, and a tattoo studio that is more akin to an art space than an ink parlor. Not only are these examples of a new kind of retail, but the selfie-station business also repurposed a shuttered clothing store, and it draws people from all over the region.

A traditional retail store that we all recognize is one in which consumers enter the store, interact with products, purchase a product, and walk out with the product. But Richard Heapes, senior vice president of Streetworks Development asked the fundamental question, “what is retail?” In trying to understand what people love about shopping and why they go shopping, the conclusion was that retail is “any interaction between a consumer and a product, good, or service.” Contrast this with online shopping, which is simply buying a product without physical interaction or context. This understanding of retail enables the market to expand beyond the traditional retail model to encompass other elements that can include the “historic, social, functional, and organizational foundation for any downtown.”

What’s happening today is what Heapes calls “bricks and clicks,” which refers to a retailer bringing its product to the online marketplace from a brick and mortar store, or vice versa. Noting that online retailers don’t generally make a profit, Heapes highlighted that they are “feeling the need to have a storefront.” The value of a storefront over e-commerce is that the consumer can have different kinds of interactions with a product, be given service and immediacy, and have a place to return the product. Even Amazon is opening storefronts.

Retail space goes hand-in-hand with public space, and their adjacency demands that they complement each other. Dan Biederman, president of Biederman Redevelopment Ventures, stressed the importance of community engagement when designing programming for open spaces to draw on the knowledge of “those who best know the town.” Activating the downtown is critical to drawing people in, and programming should rotate uses and times so that different groups are targeted at appropriate times. For example, run a Tai Chi program at dawn, something for families in the late morning, then accommodate office workers at lunchtime, students in the afternoon, and residents in the evenings.

In terms of retail, the future won’t be an extrapolation of the present and there is never a “new normal” for retail because it evolves in unpredictable and innovative ways, according to Michael Berne, president of MJB Consulting. Considering the economic impact of the pandemic, there was a relatively low fallout for businesses as a whole, which Berne attributes not only to things like eviction moratoriums and community goodwill, but to the ability of businesses to pivot. He wants to dispense with the idea that the macro-level oversupply of retail space overburdens downtowns because retail happens at the micro level, leaving open the likely possibility that any given downtown is leaking sales. There are various retail models that don’t ascribe to the traditional, capture the benefits of both “bricks and clicks,” and are able to evolve and be resilient. For Berne, signs of the market point to “better days ahead” for downtown retail.

For downtowns to hope for better days, local zoning and land use needs to be ready for it. Phil Abramson, founder and CEO of Topology NJ, frames the responsibility of local planners in terms of needing to focus on downtown growth, empowerment, and innovation. A post-pandemic geography—where most homebuyers and corporate site selectors are bound for suburban downtowns—is emerging very quickly. Abramson warns that, “location matters more than ever” in markets and economies, and towns need to step up with things like zoning flexibility, intentional public space design, and streamlined permitting for new and innovative uses. Along with responding to changing needs, planners need to recognize the inequities brought into sharp focus by the pandemic.

Westfield Mayor Shelley Brindle, who moderated the session, said it best by declaring that “great downtowns with a vibrant retail presence don’t just happen. [It takes] proactive planning and ability to adapt to the times.”

The Future of New Jersey: An Economic Forecast

June 25th, 2021 by Kimberley Irby

The COVID-19 pandemic devastated New Jersey in terms of both human life and the economy, but as the state opens back up, there are reasons to be optimistic for New Jersey’s future. There are also demographic and real estate trends that we must proactively counter and remain mindful of as our economy bounces back. Jeffrey Otteau, Managing Partner and Chief Economist at Otteau Group, presented facts and figures to show where we’ve been, as well as projections to show where we’re headed, during The Future of New Jersey: An Economic Forecast keynote session at the 2021 New Jersey Planning and Redevelopment Conference.

Throughout his presentation, Otteau described how various real estate sectors have fared over the last year, and one of the most interesting trends appeared in housing. According to Otteau, “what happened in housing was completely irrational, meaning that we had an acceleration in home purchase demand during an economic contraction, [which] has never happened before in history.” Otteau noted that contributing factors include millennials reaching home-buying age, record low interest rates, and coronavirus or personal safety concerns. He also described how the dramatic shift to remote work for many people acted as an accelerant, evidenced by the fact that around 500,000 households left New York City, many seeking larger spaces and less density. However, this phenomenon is likely temporary, and it’s not clear how much of it will persist as the pandemic recedes. Additionally, with housing prices going up so quickly, Otteau predicts that there will be an inevitable correction down the road. Given that home prices have risen much faster than salaries, there must be an adjustment that follows to bring homes back to affordable levels, especially as interest rates increase, as has happened in the past (i.e., the six years of double-digit increases in housing prices from 2000 to 2005, which were followed by six years of price declines). He also noted that some of the migration out of New York City is going to reverse itself once the economy is normalized, pointing to the historical precedent for this phenomenon.

Otteau also highlighted some of New Jersey’s demographic challenges, including the trend that the state is still losing residents aged 35 to 54. He provided two possible reasons for this. First, this age group is seeking more affordable housing and can’t find it, due to high home prices. Additionally, according to Otteau, members of this age group can’t find the types of housing they want, which are smaller in scale than large, single-family suburban homes. He claims that this younger-age adult cohort will continue to leave New Jersey if the state doesn’t start producing more of the smaller-format housing units, like townhouses and small-lot single family homes, that they are seeking. Younger New Jerseyans, which comprise a crucial talent pool for employers, will be looking for housing that is both affordable and designed to their needs, according to Otteau. One of the main takeaways that Otteau imparted is that this issue is a “critical problem that we need to be talking about and figuring out ways to solve for New Jersey’s long-term economic success.” Otteau cited home rule and zoning as standing in the way of New Jersey producing the housing that it will need to attract and retain younger workers. He referenced the warehouse sprawl bill as an example of a small step in the direction of looking at things from a regional perspective and also argued that we need to rethink school funding.

The overarching message of Otteau’s presentation is that there is great cause for optimism for what happens next, economically. “Looking to the future, now that we have seen the spread of the virus slow and hospitalizations drop precipitously, we can look forward to more rapid economic recovery here in our state as the pandemic fades,” Otteau said. Unemployment claim filings have stabilized to pre-pandemic levels, and about half of the jobs that were lost have been recovered so far. Beyond the recovery that has been spurred by vaccinations, New Jersey has been the recipient and beneficiary of substantial amounts of federal stimulus dollars, which have been helpful in terms of the state’s budget and fiscal future. Additionally, spending from the federal government’s infrastructure bill, which Otteau is certain will pass, will not only provide necessary improvements to our failing infrastructure system, but will also create jobs and economic growth. Furthermore, Otteau thinks that the longer-term trend toward greater urbanization will resume post-COVID, with more growth in transit corridors and in centers.

New Jersey has certainly suffered since the pandemic began, but the good news is that we can look forward to a swift recovery. Moreover, our state has a strategic advantage, with many smaller centers and an extensive transit network. Thus, we are well-positioned to take advantage of the trends that Otteau presented. To do so, we have to ensure that we allow housing supply to keep up with demand in these places.

Web Mapping to Support Smart Equitable Cities in Community Planning

June 25th, 2021 by Andrew Tabas

“Web mapping is a supertool for planners,” according to Rowan University Geography Professor John Hasse. The Web Mapping to Support Smart Equitable Cities in Community Planning session at the 2021 New Jersey Planning and Redevelopment Conference demonstrated just that with several case studies highlighting new web mapping initiatives in New Jersey. In addition to Hasse, the panelists included South Jersey Land & Water Trust Executive Director Christine Nolan; Rowan University Assistant Professor of Planning Mahbubur Meenar; New Jersey Conservation Foundation GIS Manager Tanya Nolte; New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection Deputy Commissioner, Environmental Justice & Equity Olivia Glenn; and New Jersey Future Policy and Program Coordinator Andrew Tabas. These organizations and others are turning to web mapping to promote more equitable community planning.

Web mapping is the use of Geographic Information Systems to display information in an online map. Unlike other types of maps, web maps are interactive. Users can turn layers on and off, zoom in and out, and click popups to find information. For more information on web mapping, read the Web Mapping 101 post by Esri.

Equity should be at the forefront of community planning, according to Meenar. He explained that equality provides everyone with the same resources, while equity provides everyone with the resources necessary for their success. Figure 1 illustrates this idea. As Meenar explained—and subsequent case studies showed—equity mapping is important, because it enables comparisons of different indicators in different areas.

Figure 1: Equality vs. equity. Source: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Putting web mapping into practice, Hasse and Nolte presented a Rowan University web mapping project called NJ Map, which is designed to advance equity in community planning. The site has a variety of maps on various topics related to environmental protection, land use, and water quality. One of the maps housed within NJ Map is the Camden Conservation Blueprint, which shows the locations of parks in Camden. The map includes several layers to examine equitable access to parks. For example, as shown in Figure 2, users can view a visual representation of the acres of parkland within walking distance of Camden’s neighborhoods. Camden Conservation Blueprint was prepared with community input. For example, community members suggested the addition of a new layer to show park amenities. Involving community members in the mapmaking process can lead to a more useful final product, according to Nolte and Hasse.

Figure 2: Acres of parkland within walking distance of homes in Camden, NJ. Source: Camden Conservation Blueprint.

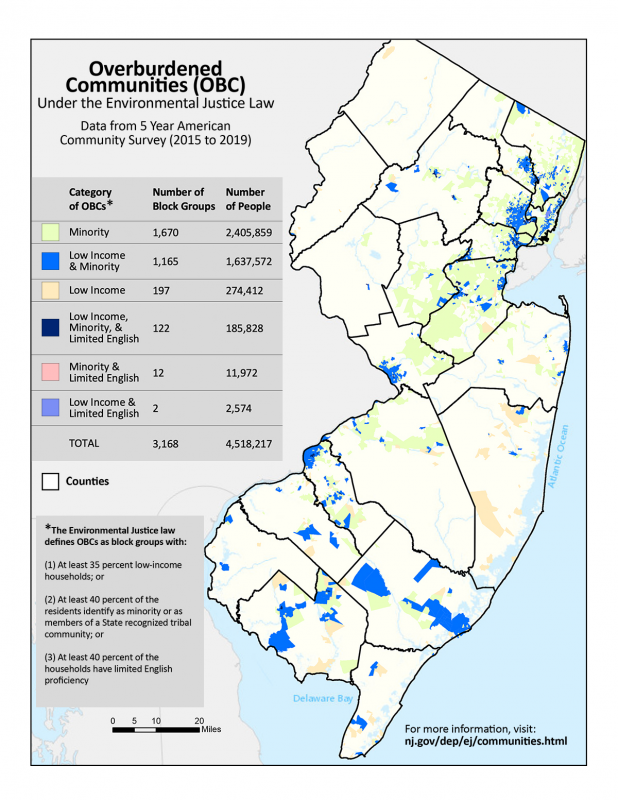

The New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) is also committed to using maps to advance equity and environmental justice in New Jersey. Glenn explained that environmental justice entails “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.” To advance environmental justice, NJDEP has defined and mapped “overburdened communities” across the state (see Figure 3). Through the new Environmental Justice Law, these communities can respond to the cumulative impacts of pollution more effectively. NJDEP has developed an Environmental Justice Mapping Tool to display detailed information about these communities.

Figure 3: NJDEP’s map of “overburdened communities” in New Jersey. Source: NJDEP.

One of the most exciting parts about NJDEP’s efforts, from a mapping perspective, is that NJDEP has made its “overburdened communities” layer publicly accessible. New Jersey Future and Jersey Water Works are making use of this layer in the New Jersey Water Risk and Equity Map, a project to explore the intersections between flood risk, water quality, and demographics. To learn more about this mapping effort, register for the Jersey Water Works Membership Meeting in July.

Web mapping can bring together geography, data analysis, planning, and environmental policy to demonstrate the need for a more equitable future. Grab your computer and start to explore the information that is available about your community!

Creating Aging-Friendly Communities Through Municipal Actions and Partnerships

June 25th, 2021 by Bailey Lawrence

While responding to the unique needs of older adults, the cultivation of aging-friendly municipalities can also benefit community members across all age groups. At the Creating Aging-Friendly Communities Through Municipal Actions and Partnerships session at the 2021 New Jersey Planning and Redevelopment Conference, aging-friendly advocates and local officials expressed the importance of aging-friendly communities and described strategies for making municipalities more inclusive for older adults.

According to New Jersey Advocates for Aging Well Executive Director Cathy Rowe, in many New Jersey communities the number of retired people will “exceed the number of students in the school system” sometime after 2030. This is the case in South Orange, where local officials were motivated to respond to such demographic trends, as well as the concerns of older residents. These concerns are sometimes neglected, especially when local officials focus on attracting younger individuals and reinvigorating downtown areas, according to Borough of Pompton Lakes Council President Erik DeLine.

Nonetheless, all speakers at the session emphasized that the needs and interests of older adults and younger people are not mutually exclusive. In fact, according to AARP New Jersey Associate State Director, Advocacy Katie York, “like many facets of age-friendly work, improved built environments can benefit all ages.”

Similarly, New Jersey Future Community Planning Manager Tanya Rohrbach said that establishing aging-friendly communities “helps to create community-wide benefits, uses resources more efficiently, and fosters community building.”

Additionally, efforts to improve the built environment for all community members can produce significant benefits for older adults. According to DeLine, prior to making a conscious effort to become an aging-friendly community, Pompton Lakes had already worked to expand local grocery store access, increase green space, and establish walkable streets. While enhancing the general community’s livability, these initiatives also helped respond to the financial, health, and safety concerns of the municipality’s older adults.

“Some of the things you’re doing can be aging-friendly, even if you’re not explicitly thinking about it,” DeLine said.

Building aging-friendly communities is especially important, according to Rohrbach, because of the failures of “aging in place” to address home design, cost, maintenance, and social isolation. “Aging in community,” on the other hand, promotes social engagement, mobility, and physical and mental wellbeing, all of which can be experienced as a result of an optimized built environment. According to Rohrbach, the built environment’s potential benefits can be maximized by implementing compact development, constructing walkable street grids, and providing a diversity of housing options.

The achievements of South Orange and Pompton Lakes are reflective of an increasing statewide commitment to aging-friendly communities. New Jersey recently became the ninth state to join the AARP Network of Age-Friendly Communities and States.

All speakers at the session highlighted the impact of collaboration between local community groups and municipal governments. “Great places don’t make themselves or happen by chance. We have to be proactive, and a big part of that includes municipal action,” Rohrbach said. In November 2020, New Jersey Future (NJF) published Creating Great Places to Age in New Jersey: A Community Guide to Implementing Aging-Friendly Land Use Decisions in order to support the state’s municipalities in their efforts to foster aging-friendly communities.

NJF also conducted an aging-friendly land use assessment in Pompton Lakes, which helped the municipality identify the need for an amplified diversity of housing options, according to DeLine. DeLine said that, according to the municipality’s findings, more than half of its 65-and-older residents were cost-burdened. In order to more effectively engage in aging-friendly work, Pompton Lakes hired an aging-friendly coordinator. Furthermore, DeLine said that the municipality is seeking to amend its accessory dwelling unit ordinance in order to provide a greater array of affordable housing options.

Meanwhile, South Orange supported its aging-friendly work by developing a new master plan, which is the “most comprehensive and inclusive” New Jersey master plan to date, according to Rowe. Community engagement and participation, especially among older residents, were crucial throughout the process of establishing South Orange’s master plan. According to Rowe, the municipality held more than 46 separate engagement events (three of which were organized for older residents, specifically) and facilitated online engagement efforts.

“The best plans or the best policies really [mean] nothing if people don’t know about [them]. It was important for us to get the word out and keep people constantly informed,” Rowe said.

Community Benefits Agreements: Understanding the New Requirement and How to Create a Win-Win

June 25th, 2021 by Kimberley Irby

Given that Community Benefits Agreements (CBAs) are built into the structure of the New Jersey Economic Recovery Act, which was signed into law in January 2021, it is no longer a question of if they will happen, but when they will happen. This is what Kelvin Boddy, Director of Healthy Homes and Communities at the Housing and Community Development Network of New Jersey, explained during the Community Benefits Agreements: Understanding the New Requirement and How to Create a Win-Win session at the 2021 New Jersey Planning and Redevelopment Conference. The session featured explanations of what CBAs are, how they are incorporated in the new law, and best practices for ensuring successful ones.

What are CBAs and what types of benefits can they include?

CBAs are “legally binding agreements that relate to a single development and apply to all parties that deliver on it, including developers, contractors, and future tenants,” according to Ben Beach, Legal Director at the Partnership for Working Families, which hosts the Community Benefits Law Center. Ebony Griffin, Staff Attorney at The Public Interest Law Center, added that CBAs are enforceable contractual agreements between a community group and a developer or corporation that describe the project’s contributions to the community and generate community support for the project. Potential benefits include living wages and benefits, targeted and fair-chance hiring, affordable housing, environmental mitigation, small business support, and community services (e.g., grocery stores, public art, meeting spaces, health clinics, and/or workforce development).

What is important to know about the requirement in the Economic Recovery Act?

“New Jersey is the first state in the country to require CBAs in a statewide tax incentive program,” said Brian Sabina, Chief Economic Growth Officer at the New Jersey Economic Development Authority (NJEDA). Dr. Robert Silverman, a professor within the Department of Urban and Regional Planning at the University of Buffalo, emphasized that this institutionalization of CBAs at a state level represents a “sea change in terms of how CBAs fit into the development process.” Having such a framework will increase predictability in the development process for developers, community groups, and local governments.

Mr. Sabina explained that, for two flagship programs established by the Economic Recovery Act (Emerge and Aspire), CBAs are required for projects with total upfront project costs of $10 million or more and will constitute a tri-party agreement between a business, a municipality or county (the negotiator), and NJEDA (the reviewer). Additionally, the governing body of the municipality or county must set up at least one community engagement session prior to finalizing the CBA. Then, after entering into a CBA, the municipality/county executive must appoint a Community Advisory Committee, which will have at least three community members to monitor implementation and report progress to NJEDA annually.

What are best practices for CBAs?

Ben Beach provided three core principles that are necessary for an effective CBA: accountability, meaningful benefit, and democratic participation. Other panelists agreed that for a CBA to be successful, the terms should be specific and measurable, easily implemented, and effectively monitored and enforced. They also agreed that the benefits must meet real community needs, especially for communities that are not only directly impacted, but are generally excluded from economic development opportunities, as well. Ebony Griffin emphasized the importance of this, demonstrating through a case study that if this is not achieved, the developer may not receive the public support needed for a profitable project. In terms of democratic participation, Beach indicated the need for broad representative community involvement and the application of a racial equity lens to the entire process, both in terms of participation and outcomes. Griffin supported this, maintaining that an inclusive and transparent process is a guiding principle. Ultimately, effective CBAs require substantial community organizing and engagement to provide communities with a legitimate opportunity to bring their needs forward.

What’s next?

For community development groups, Boddy claims that there is no reason to wait for projects to pop up to start preparing communities for them. The Housing and Community Development Network of New Jersey is already in the process of integrating CBAs into its programs. It will host trainings, as well as a workshop, at its October conference to educate its member groups about the legal requirements, navigating the process, and preparing residents to advocate and negotiate for sustainable changes.

CBAs, when done well, can serve as a powerful tool for equitable development and redevelopment, simultaneously addressing community needs and providing broad support for the developer’s project. The Economic Recovery Act provides a new framework that may lead the way to making successful CBAs more common in New Jersey.

Two Homes, One Roof: Making NJ More Welcoming with ADUs

June 25th, 2021 by Tim Evans

Accessory dwelling units (ADUs) are an often overlooked and underutilized solution to the affordable housing shortage we face in New Jersey and across the Northeast. An ADU can be built as a separate dwelling unit in the backyard of a detached home on a single-family lot, or can be created from existing space by converting a garage, basement, or attic, or can be built as a self-contained addition onto an existing single-family home.

At the 2021 New Jersey Planning & Redevelopment Conference, co-hosted by New Jersey Future and the New Jersey Chapter of the American Planning Association, a session entitled Two Homes, One Roof: Making NJ More Welcoming with ADUs discussed the importance of ADUs and their potential as a strategy for increasing the state’s housing options. Speakers included Nat Bottigheimer, New Jersey Director of the Regional Plan Association, Dean Dafis, Deputy Mayor of Maplewood Township, Christine Newman, Director of Community Outreach at AARP New Jersey, Mia Sacks, Councilwoman for the Municipality of Princeton, and Julia Stoumbos, Director of the “Aging in Place” program at the Henry and Marilyn Taub Foundation.

Nat Bottigheimer talked about the Regional Plan Association’s July 2020 report Be My Neighbor, which outlined strategies to create more homes and emphasized how valuable ADUs can be for seniors who want to age in place, families who’d like to earn extra income from their home, and anyone who cannot afford a single-family home. Julia Stoumbos seconded the point about seniors, noting how ADUs can help solve many of the challenges that confront people seeking to remain in their community as they age. “The prohibitive cost of maintaining a home is one of the most commonly mentioned challenges in surveys of older people,” she said. Moving into an ADU reduces the responsibilities for maintenance, and also reduces or eliminates the need to pay property taxes, which Stoumbos cited as another frequent obstacle to aging in place for older people no longer earning a steady income.

Christine Newman talked about the surging growth in the 65+ population, as the Baby Boomers age into retirement, and the need for housing markets to adjust to this reality. Adults living alone (including a substantial number of older people) now account for 30% of all households, but Newman observed that “housing markets remain fixated on the ‘nuclear family’ household and the single-family-detached house. We need to expand our imagination, in terms of the types of housing units we build.” She said we need to rediscover how to include ADUs in our housing stock, along with many other types of “missing middle” housing that were common up through the 1940s.

A major obstacle to ADUs is that local zoning often does not allow them. How do we change that? Maplewood and Princeton have each made progress promoting diverse and inclusive housing, and Mia Sacks and Dean Dafis each talked about how they shifted public opinion in favor of needed zoning changes in their respective towns. Both local leaders observed that the best way to sell ADUs to the public is to describe them as a way to help older residents age in place. Sacks said she even used her own mother as an example of how ADUs can enable seniors to continue paying their property taxes. Newman echoed the importance of getting local residents to tell their stories, saying that “personal stories are key for community engagement and buy-in, especially when it comes to NIMBY-ism (Not In My Back Yard). They reframe the conversation from ‘they/them’ to ‘us/we’.”

For towns that are open to allowing ADUs, Newman said that AARP has a model local ordinance that towns can use as a guide. As another resource for building support for such an ordinance, she also pointed to AARP’s 2019 report The ABCs of ADUs, which provides a primer for communities interested in better understanding how ADUs support Age-Friendly Community Building.

But Dafis said municipal leaders need state laws to support their efforts to make ADUs available to everybody who needs them. The panelists agreed that they wished public sentiment were more open to offering opportunities to the many kinds of people that could benefit from living in an ADU, not just older people who already live in town. Dafis said a major challenge is overcoming existing residents’ stated concerns about “changing the character of the community,” language he said harkens back to the country’s ugly history of redlining, in terms of using housing laws to keep out certain kinds of people. Bottigheimer commented that Connecticut recently passed a law that bans the use of “character” in local land-use ordinances unless the town can quantify what it means by that term. A similar bill in New Jersey that permitted ADUs “as of right” might help to undo the state’s status as one of the most segregated in the country.

Geography of Equity and Inclusion: The Big Picture

June 24th, 2021 by Bailey Lawrence

Spatial segregation persists across the United States and continues to result in economic, educational, and health disparities. Nonetheless, according to several planning professionals and activists, equitable approaches, processes, and strategies can help mitigate spatial segregation in New Jersey. At the 2021 New Jersey Planning and Redevelopment Conference, the Geography of Equity and Inclusion: The Big Picture plenary session featured five panelists, including Smart Growth America President and CEO Calvin Gladney, Latino Action Network President Christian Estevez, Fair Share Housing Center Deputy Director Eric Dobson, Tri-State Transportation Campaign Executive Director Renae Reynolds, and David Troutt, Professor of Law and Founding Director of the Rutgers Center on Law, Inequality and Metropolitan Equity (CLiME), Rutgers University. The panel was moderated by New Jersey Future Executive Director Peter Kasabach, and opening remarks were delivered by New Jersey Future Board Members: Cooper’s Ferry Partnership Vice President Meishka Mitchell, AICP, PP, City of Hoboken Director of Community Development Christopher Brown, and Maraziti Falcon LLP Partner Joseph Maraziti.

The speakers provided an overview of spatial segregation in New Jersey, while analyzing the origins of these disparities.

“New Jersey is one of the most diverse states, but it is also one of the most segregated states,” Dobson said. In fact, according to Gladney, “we are getting more segregated year after year” in New Jersey and across the country.

Gladney emphasized that spatial segregation was deliberately established and continues to be purposefully maintained. “It’s not a bug in the system,” Gladney said. “It’s a feature of the system to churn out inequity.” These features include single-family zoning, interstate highways, and redlining.

Such planning decisions, according to Reynolds, have “left communities bifurcated by highways and suffocated by the pollution that comes from the transportation sector.”

Troutt said that, as professionals in the planning field, we must study and act upon these instances of institutional harm, rather than merely acknowledging them in passing. For example, Brown explained that Hoboken’s Master Plan considered how the city’s zoning has motivated the proliferation of larger and more expensive dwellings.

Spatial segregation has important implications for opportunities and health outcomes, and its manifestations may appear in virtually every facet of New Jerseyans’ daily lives.

“Where you live and where you were born can dictate your access to open space, clean drinking water,” and other life necessities, Mitchell said.

During his keynote presentation, Gladney explained that low-income units are being built increasingly further away from transit access across the country, and New Jersey is especially reflective of this trend. On the other hand, the walkability of poor New Jersey neighborhoods is much greater than that of other states’ poorer neighborhoods.

Furthermore, Gladney demonstrated that, in many cities in the United States, the hottest areas are located in the poorest neighborhoods. In many cases, these are the same neighborhoods that were redlined nearly a century ago. Climate change and rising temperatures will disproportionately impact these neighborhoods, which did not receive sufficient investments in the form of tree canopies and porous and/or reflective pavement. Communities most vulnerable to increasing flooding are disportionately the homes of poorer people, as well, Gladney said.

However, the speakers described ongoing initiatives that seek to inhibit spatial segregation and prescribed tactics that conference attendees can utilize in their own communities.

For example, Maraziti emphasized the importance of negotiating community benefits agreements, which can help foster more equitable neighborhoods.

In terms of the transportation sector, Reynolds discussed the Tri-State Transportation Campaign’s efforts to expand the times of transit service, increase access to New Jersey’s trails, and generate connections from “rails to trails.”

“The pandemic brought to light the need for more access to green space,” Reynolds said.

The speakers also outlined strategies in the housing realm that may help combat spatial segregation. Dobson urged urban jurisdictions—especially cities in which gentrification is an intensifying threat—to more consciously implement inclusionary zoning. In Hoboken, for example, the City is adjusting the zoning code to promote housing diversity and affordability, Brown said.

Nonetheless, both Dobson and Estevez acknowledged that it will take decades to truly achieve residential desegregation. Estevez said that, in the meantime, communities must work to expand access to equitable education. Through its ongoing legal efforts, the Latino Action Network is attempting to “realize the promise of Brown” and produce “[really] integrated schools, and then hopefully housing that follows.”

Many of the speakers acknowledged this historical moment as a unique opportunity to effect substantive change and provided effective strategies to conceptualize and evaluate equity.

During this “age of equity,” said Troutt, we must “recognize that the Mt. Laurel doctrine is really about affirmative aspirations. It’s not just about the least that we can do, but the most that we can think about doing.” In order to achieve equitable outcomes, analysis must help formulate “specific equity targets,” and practitioners must engage in “serious compliance, reconciliation, and accountability,” Troutt said.

“We have to make decisions [and] investments with equity in mind” and “centering racially equitable outcomes and fixing racial disparities as the core” of decision-making, Gladney said.

Water, Water Everywhere—Achilles Heel or Asset?

June 24th, 2021 by Missy Rebovich

Water is essential for life, but the infrastructure that brings it into our homes—or keeps it out of our basements—is only considered when something goes wrong. At the 2021 New Jersey Planning & Redevelopment Conference session Water, Water Everywhere—Achilles Heel or Asset? panelists discussed why water can no longer be treated as an add-on issue to which communities simply react. Moderated by Chris Sturm, managing director, policy and water at New Jersey Future, the session featured George Hawkins, founder and CEO of Moonshot Missions; Jennifer Gonzales, director of environmental services, City of Hoboken; Meishka Mitchell, vice president, Cooper’s Ferry Partnership; and Lisa J. Plevin, executive director, New Jersey Highlands Council.

One way to infuse consideration of water into planning and decision-making is by local ordinance. Hawkins explained how Washington, D.C. changed its development and redevelopment ordinance to highlight stormwater capture in response to increasing flooding during rainstorms. “This started 10 years ago and has gotten stronger over time. You must capture in a new project or a redevelopment project 1.2 inches of rainfall on site. That’s required to get your permit to do the redevelopment. But flexibility is built in, so if you can’t do it on-site, there’s a mitigation bank, like a wetland mitigation bank, but for green infrastructure.”

Developers encountering site constraints to green infrastructure can pay into the fund, which allows the District Department of Environment to construct green infrastructure elsewhere with the same criteria. The bank creates a marketplace to ensure green infrastructure is generated by all new development.

In the New Jersey Highlands, municipalities are required by state law to update their master plans in conformance with the Highlands regional master plan. “Protecting water resources in the Highlands region is critical,” said Plevin. “Because, while the region makes up less than 20% of the population of our state, it is the source of drinking water for over 70% of the state’s residents.”

Plevin noted that “clean, plentiful water is really important; however, municipalities are often focused on their own local boundaries and not on watershed boundaries.” That’s why the New Jersey Highlands Council works closely with the region’s municipalities and counties to ensure local plans are developed in ways that maximize water resource protection.

In Hoboken, an urban coastal city with a combined sewer system, local leadership is acutely aware of the importance of stormwater management. In order to leverage capital, Gonzalez explained, the City looks to multi-benefit projects. For example, Hoboken’s Washington Street Redesign project—which won a New Jersey Future Smart Growth Award in 2020—involved replacing drinking water infrastructure across 15 blocks of the city. This work allowed the City to install complete streets upgrades at the same time, installing four green/gray infrastructure projects involving porous pavement and underground detention basins in the public right-of-way.

“We employ a One Water approach where we can manage drinking water and manage stormwater all through one capital plan,” said Gonzalez.

Community organizations—and community members, themselves—play an important role in connecting water issues to city planning. Camden’s century-old combined sewer system has received lots of attention from residents experiencing frequent contaminated flooding. Mitchell explained, “In the early 2000s, Cooper’s Ferry Partnership began to think about planning and redevelopment on a neighborhood scale. It was when we started to do more neighborhood-driven community outreach that we began to really understand the impact water was having in the city and how we needed to address it.”

As much as the residents learned about water infrastructure, Mitchell says she learned more from the residents. Community members addressed local flooding as their number one issue, which helped the local government see its impact, including on a young student who expressed concern that her school bus wouldn’t be able to make it to take her to school during a rain event. “Water infrastructure, whether combined sewer flooding, lead pipes, or water quality, impacts residents far more significantly than those in government could imagine. Until we talk to those residents, we won’t get a full understanding of what that means” Mitchell said.

Cooper’s Ferry Partnership has been working with the City of Camden to incorporate green infrastructure into everything it can—from art installations, to park development, to new building development—and making sure that water infrastructure is part of the planning process, keeping residents front and center.

Panelists noted that funding can be a significant barrier to implementing green infrastructure and other water infrastructure projects. In Camden, Mitchell found that her nonprofit organization and the City, working collaboratively and creatively, can leverage each other’s resources to move critical projects forward. Hawkins shared that D.C. implemented a stormwater utility to fund stormwater infrastructure upgrades, and Hoboken is investigating how it can do the same.

Keeping water at the forefront of planning is key to the health of our communities. By working together, government leaders, utilities, community groups and members can develop and implement plans that will make our cities and towns strong and resilient for centuries to come while protecting our most valuable natural resource: water.

Incorporating Climate Change: It’s the Law

June 24th, 2021 by Tim Evans

Earlier this year the legislature passed and the governor signed into law an amendment to the New Jersey Municipal Land Use Law (MLUL) requiring a climate change-related hazard vulnerability assessment.

What does this change mean for municipal officials? What will they be required to do and when? This was the topic of discussion in a session entitled Incorporating Climate Change: It’s the Law at the 2021 New Jersey Planning & Redevelopment Conference, co-hosted by New Jersey Future and the New Jersey Chapter of the American Planning Association.

Moderated by Leah Yasenchak, Principal at BRS, Inc., the panel included Jon Drill of Stickel, Koenig, Sullivan & Drill, LLC; Jessica Jahre, Senior Planner at the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (DEP); Anthony Mercantante, Township Administrator of Middletown Township; and Stan Slachetka, Group Manager at T&M Associates.

Jon Drill pointed out that the MLUL amendment falls under the section that lays out the required elements of a municipal land-use plan. The preparation of a climate change and hazard vulnerability assessment is thus triggered by any update of the land-use plan. Since many municipalities are going to have to update their master plans in order to satisfy their affordable housing requirements, they will also have to look at completing these vulnerability assessments as part of that process.

As to what needs to be in the assessment, Stan Slachetka mentioned that some municipalities have more climate-change-related vulnerabilities than others. Coastal municipalities are at special risk from sea-level rise, but all municipalities will be affected in some way, whether from increased temperatures, storm intensity, increased rainfall and stormwater runoff, fire risk, etc. Slachetka said probably the best way to think about a climate risk assessment is through the lens of a build-out analysis, in which a municipality considers what land uses would be located in vulnerable areas if everything called for in the master plan got built. If a town’s master plan and zoning are calling for development in areas that will be flood-prone in the future, for example, this should be a prompt to reexamine the zoning and redirect future development.

How do municipal leaders know what land uses are located in “vulnerable areas,” both now and in the future? Jessica Jahre announced that NJDEP has created a website, Resilient NJ, to help municipalities plan for climate change. She said its primary objective is “to accelerate community resilience planning,” and that “there is something in there that will be of interest to every town.” In particular, the website includes a toolkit designed to walk municipal leaders through the process of identifying their areas of vulnerability to climate change. The toolkit not only helps municipal leaders assess their risks but also contains a database of over 300 local actions that could be taken to address those risks, along with case studies, allowing municipalities to tailor their responses to their particular situations.

Slachetka suggested that municipalities should use these tools to ask what is their level of risk on various factors, what areas are affected, what is located there, and who lives there. He advised municipal leaders to look especially at “critical facilities” (e.g., utility lines, roads, public buildings) that are located in vulnerable areas and to identify which elements of the land-use plan potentially need to be updated to address these locational vulnerabilities.

Anthony Mercantante talked about the unusual situation in Middletown Township, which comprises numerous component neighborhoods with a diverse array of demographics. In contrast to the pattern typical of most coastal municipalities, Middletown’s neighborhoods along the Raritan bayshore (North Middletown, Port Monmouth, Belford, and Leonardo) actually have lower average home values than the inland neighborhoods, reflecting the generally lower-income profile of the residents. One of these neighborhoods, Port Monmouth, has recently been protected by a flood control project funded by the Army Corps of Engineers, involving flood walls, flood gates, and pumps. The design of the project had been on the Army Corps’s books since the 1990s, but it only actually got built in the wake of Superstorm Sandy. Mercantante indicated that these physical reinforcements are effective – North Middletown already had flood walls and did not flood during Sandy. But the infrastructure is expensive, sometimes involving land acquisition.

Infrastructure projects like the one in Port Monmouth are also reactive. The MLUL amendment is designed to instead encourage local governments to think proactively, the better to get residents and critical facilities out of harm’s way before the next disaster strikes.

Tracking Progress on Environmental Justice

June 15th, 2021 by Tim Evans

The Murphy administration has made environmental justice a priority, pledging to end the siting of environmental hazards in neighborhoods where low-income people and/or people of color live—and especially neighborhoods that are characterized by the presence of both low-income households and people of color. In September 2020 the Environmental Justice Law was passed by the state legislature and signed by Governor Murphy to protect disadvantaged communities from further exposure to environmentally hazardous land uses.

The law defines “overburdened communities,” which will benefit from the new protections. An overburdened community is any census block group in which any of the following conditions is met:

- at least 35 percent of households qualify as low-income households (at or below twice the poverty threshold, as determined by the United States Census Bureau); or

- at least 40 percent of residents identify as minority or as members of a State-recognized tribal community; or

- at least 40 percent of households have limited English proficiency (without an adult that speaks English “very well,” according to the United States Census Bureau).

The law is written to address the question of where not to locate certain types of facilities in the future. However, the administration has also indicated that it will prioritize the improvement of environmental conditions in overburdened communities when making decisions about where to invest in clean energy and other technologies designed to reduce the state’s carbon footprint, many of which will result in reductions in traditional pollutants, as well. The administration seems to want to use the newly defined concept of an overburdened community in a more proactive sense, rather than an exclusively reactive one.

One of the first situations in which this commitment will be tested is in the spending of proceeds from the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) program. Participating states are required to use the proceeds from CO2 allowance auctions for programs that are designed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and increase the use of clean energy sources, but it is up to each state to decide exactly where (geographically) this money will be spent. In theory, there is nothing to stop a state from spending its RGGI money mainly on charging stations for electric vehicles in upscale suburbs, for example, which would do nothing to improve conditions in the communities that have historically suffered the most severe pollution impacts. But, New Jersey has already taken steps to assure the public that this will not happen.

The NJ Department of Environmental Protection, which is coordinating efforts among the three state agencies1 charged with spending RGGI proceeds, has set up a RGGI Climate Investments Dashboard, where information about projects receiving RGGI funding will be made publicly available. To date, 19 projects have been added to the dashboard, all of which involve electrified municipal vehicles of various types (garbage trucks, shuttle buses, school buses, etc.). As more programs are finalized and application periods close, information about the awardees will be added.

The dashboard allows projects to be filtered and displayed according to various subsetting criteria, one of which is whether the project is located in an environmental justice (EJ) community. The overburdened community block groups are also illustrated on a map on the dashboard, and users can examine the locations of funded projects with respect to EJ community boundaries. Thus far, all projects have been tagged with the EJ flag because, in each case, the electric vehicle will be operating in a municipality that contains at least one EJ block group. However, the assignment of EJ status for mobile projects is not as straightforward as is the case for projects having a fixed location, in which case a building or other permanent facility is clearly either inside or outside an EJ block group. Electric vehicles, by contrast, may only spend part of their time in EJ block groups.

The development of tracking metrics is an ongoing process. New metrics may be added to the dashboard in the future, and others that do not lend themselves to graphic display may be tracked behind the scenes. In particular, if a methodology can be developed to distinguish the uses and benefits of non-stationary projects, such as electric vehicles, between EJ and non-EJ areas, New Jersey Future will continue to encourage state agencies to officially adopt such metrics and make results public. More generally, we will continue to provide feedback on proposed metrics for tracking progress on environmental justice as more RGGI-funded programs gear up and are added to the dashboard. As the dashboard user manual says, “The public needs to know how administering agencies are investing RGGI proceeds and what benefits are being achieved from those investments.”

While these investments are taking place, the State is contemplating joining the Transportation Climate Initiative (TCI). TCI is similar to RGGI but with a focus on the transportation sector. TCI discourages fossil fuel consumption in the transportation sector while generating funds that can be invested in cleaning the transportation sector, such as investments in alternatives to driving. Having good metrics and a tracking system in place, as they are doing with RGGI, will put the State in a good position to invest TCI proceeds wisely should they come to pass.

1 The Board of Public Utilities and the Economic Development Authority are the other two agencies.