New Jersey Future Blog

Census 2020: New Jersey’s Older and Increasingly Diverse Centers Are Now Leading The State’s Population Growth

September 13th, 2021 by Tim Evans

The demographic story of the 2010s in New Jersey was the return of population growth to the state’s walkable, mixed-use centers—cities, towns, and older suburbs with traditional downtowns. Driven in particular by the Millennial generation’s desire for live-work-shop-play environments in which a car is not necessarily needed for every trip, many of the state’s older centers experienced their biggest population increases since before the 1950s.

Newark, the state’s largest city, grew more than twice as fast as the rest of the state this decade, growing by 12.4% between 2010 and 2020 compared to 5.7% for the state as a whole. This is the first time in many decades that Newark has outpaced the statewide growth rate, and 2020 also marks the first time since 1985 that New Jersey has had a city with a population of more than 300,000. Newark’s population dipped below 300,000 in 1986 and continued to decline to a low of 262,862 in 1998 before reversing its slide.

Jersey City, the state’s second-largest city, has been perhaps the most visible star in New Jersey’s urban revival. Its resurgence actually predates the national trend by several decades (Jersey City’s population decreased in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, but began growing again in the 80s). It grew slowly at first, lagging behind the statewide rate until 2010, but between 2010 and 2020 it grew at more than three times the statewide growth rate (18.1% vs. 5.7%). Like Newark, Jersey City once had more than 300,000 residents, but dropped below that mark in 1950, eventually falling to a low of 220,857 in 1979. But having added almost 45,000 people in the 2010s, its population now stands at 292,449 and is poised to once again surpass 300,000 in the coming decade if its 2020s growth looks anything like its 2010s growth.

The growth of traditional centers is not limited to the state’s biggest cities, however. The 124 New Jersey municipalities that best embody the concept of walkable urbanism and score high on all three New Jersey Future smart growth metrics—high activity densities (people + jobs per square mile), mixed-use downtowns, and well-connected, walkable street grids—together grew by more than 1.5 times the statewide growth rate, accounting for more than half (57.5%) of the statewide population increase in the 2010s, compared to only 13.6% of total growth in the 2000s. Most of these cities, smaller towns, and walkable, first-generation suburbs experienced their peak growth many decades ago. In fact, many of them actually lost population at some point since the 50s.

In contrast, the 158 municipalities with the most car-dependent development patterns—characterized by low densities, single-use subdivisions, and branching street networks that require circuitous car trips—grew by only half the statewide rate in the 2010s (2.8% vs. 5.7% statewide). This is a dramatic change from previous decades; this same group of municipalities grew by 7.1% between 2000 and 2010 and accounted for more than one-third (35.9%) of statewide population growth that decade after comprising 37.8% of the statewide increase in the 90s and 63.8% in the 80s. Younger generations’ preference for in-town living has substantially curbed demand for new subdivisions at the exurban fringe.

The state’s older centers also significantly contribute to New Jersey’s status as one of the most racially diverse states in the country. Much of the media coverage of the release of 2020 Census county and municipal populations focused on increasing diversity, both at the state and local levels. In New Jersey, it’s in the compact, walkable centers where the state’s diversity is most evident. Using a concept called the diversity index, which the Census Bureau uses to show “the probability that two people chosen at random will be from different race and ethnic groups”1 (the higher the score, the more diverse the community), New Jersey’s overall diversity index was 65.7% in 2020, up from 59.3% in 2010. Of the state’s 565 municipalities, 215 have a diversity index greater than 50%, and of these 215, 93 are among the 124 municipalities referenced above that score well on all three New Jersey Future smart growth metrics. Thus, among the municipalities with the most center-like development patterns, 75% (93 out of 124) have a diversity index of 50% or more. In contrast, among the 158 most sprawling, car-dependent municipalities that do not score well on any of the three metrics, only 22.8% (36 out of 158) exceed 50% on the diversity index. (The other two groups of municipalities—those scoring well on either one or two of the metrics—follow the same pattern, in which a greater number of high scores on smart growth metrics is associated with a higher likelihood of having a diversity index of 50% or more.)

New growth in older centers is happening, in part, thanks to the rise of redevelopment—the reuse of land that had previously been developed for some other purpose—as New Jersey’s default development pattern. The 270 New Jersey municipalities that were at least 90% built-out as of 2007 together accounted for nearly two-thirds (65.1%) of the state’s population increase in the 2010s, after having contributed just 12.2% of the statewide increase in the 2000s. That the state’s population growth is now dominated by redevelopment areas represents a remarkable shift compared to the several preceding decades, which were characterized by low-density growth on the suburban fringe. The trend toward redevelopment illustrates that “built-out” does not mean “full,” and that there are plenty of opportunities to absorb new residents in the state’s cities, towns, and older suburbs.

Creating new opportunities for growth in these older centers is key to attracting and retaining members of younger generations who are looking for an in-town lifestyle. New Jersey should focus on reforming local zoning to allow more of the kinds of housing younger households are looking for (e.g., townhouses, duplexes, small apartment buildings, apartments above stores, smaller single-family homes on small lots) in the kinds of places they want to live. Encouraging growth in already-developed areas has the added benefit of using our transportation and energy infrastructure more efficiently and avoiding the building of new sprawling infrastructure and then having to maintain it. The move to redevelopment also takes pressure off the state’s remaining open lands, helping to preserve the state’s overall quality of life by allowing those lands to continue being used for agriculture, recreation, and wildlife habitats.

1The diversity index is dependent on the number of different mutually-exclusive race categories that are used in the analysis. The Census Bureau uses eight categories in its analysis. New Jersey Future’s analysis condenses these to five—non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Asian, and other—by grouping four of the Census Bureau’s categories into the “other” group, because their numbers are individually very small in New Jersey. Using five categories, the index has a maximum value of 0.8, or 80%.

Lead in Drinking Water in Public Schools: State Assistance Accelerates the Solution in New Jersey

September 13th, 2021 by Gary Brune

Photo credit: Canva

When New Jersey’s public schools were last tested for lead in drinking water in 2016, the extent of potential exposure was pervasive. Based on research conducted by the Trenton Bureau of the USA TODAY Network in 2019, approximately 480 school buildings across a third of the state’s school districts recorded lead levels that exceeded 15 parts per billion, the action level set by the federal government. Given the severity of the problem and the significant cost of remediation, it was clear that state assistance was necessary to protect students and teachers.

On July 1, 2021 Governor Murphy signed legislation (A-5887) that appropriated $6.6 million in state grants for water infrastructure improvements in public schools. This represents the first issuance of grants authorized under the Securing Our Children’s Future program administered by the NJ Department of Education (NJDOE). A total of $100 million in state bonds was approved for this initiative by voters in November 2018. The subsequent regulations promulgated by the NJDOE identified two categories of eligible projects: improvements to drinking water outlets and remediation of major segments of a school’s water distribution system (e.g., replacement of lead service lines or wells).

The approved grants include a $4.1 million appropriation for Jersey City, as well as Shore Regional’s (Monmouth County) plan to use part of its $70,721 grant to install an automated flushing system, a new, low-cost technology that has been successfully implemented elsewhere to keep lead from leaching from pipes into water.

Anecdotally, it appears that the pandemic limited the number of applications submitted to the NJDOE as school districts focused on securing federal aid to ensure ongoing operations. According to the Department, the next round of grants (funded by approximately $93 million in remaining funds) will be issued after the districts perform their cyclical testing of lead in drinking water, which must be completed by the end of June 2022. (This link provides an overview of the NJDOE’s testing-related regulations under N.J.A.C. 6A:26-12.4.) The NJDOE’s approach will help ensure that the next round of grant applications is based on the latest testing results.

The NJDOE issued a broadcast on July 2, 2021 notifying those districts whose grants were approved by the Legislature. The full list of substantially approved grants can be accessed on the Department’s School Facilities webpage.

New Jersey Needs More “Missing Middle” Housing

July 19th, 2021 by Tim Evans

Aerial photo of Trenton, NJ.

- New Jersey’s housing costs are among the highest in the country. The state ranks seventh in median home value and fourth in median rent.

- The state is losing younger households to other states, and evidence points to high housing costs as one of the reasons.

- To create more of the kinds of homes that younger households are looking for—in the neighborhoods they want to live in—New Jersey should consider revising the zoning and parking requirements that determine what kind of housing gets built and where.

A recent Rutgers-Eagleton Poll, in collaboration with the Housing and Community Development Network of New Jersey, found that 90% of New Jerseyans are worried about the cost of housing in the state, with 55% considering it a “very serious” problem and another 35% saying it is “somewhat serious.” And 80% feel the same way about finding an affordable place to rent (49% “very serious” and 32% “somewhat serious”).

They are not wrong to worry—New Jersey is an expensive state. As of the 2019 one-year American Community Survey1, New Jersey’s median gross rent of $1,376 is the fourth-highest in the nation after Hawaii, California, and Maryland. And on median home value (self-reported), it ranks seventh after Hawaii, California, Massachusetts, Colorado, Washington, and Oregon.

To a certain extent, this is a function of New Jersey’s status as a high-income state—our median household income of $85,751 is the third-highest in the country after Maryland and Massachusetts. It is broadly true that the states with the highest housing costs also tend to have the highest incomes (Hawaii, California, Washington, and Colorado all also appear in the top 10 for household income). Typically, the higher a household’s income, the more it is able to spend on housing.

Living with Parents

For younger New Jerseyans on the lower end of the income ladder, however, high home prices and rents can present a significant barrier to forming their own households and staying in New Jersey when they do move out on their own. New Jersey has the highest incidence among the 50 states of people ages 18 to 34 living with their parents (45.4%, or nearly half). Only Connecticut (41.7%) and Rhode Island (41.1%) also exceed 40%, with notoriously expensive California just behind at 39.5%. (The national rate is 34.0%.) When faced with an expensive housing market, many younger New Jerseyans choose to delay getting their own place.

Paying More Than You Can Afford

An extended post-graduation stay with parents is one way to save on rent or to save up to buy a house. But not everyone finds this option feasible or desirable. Some will just bite the bullet and spend more on housing than they can realistically afford. Indeed, New Jersey has the fourth-highest rate among the 50 states of households paying more than 30% of their gross income on housing costs (such households are considered “housing-cost burdened”), behind only California, Hawaii, and New York. The percentage is unsurprisingly higher among renters than homeowners, as is true elsewhere—nationally, 48.4% of renter households are cost-burdened, compared to only 21.3% of homeowner households. But New Jersey actually only ranks 12th-highest when looking exclusively at the rate of housing cost burden among renters—its rate of 49.0% is only slightly higher than the national rate.

Where New Jersey stands out is in its cost-burdened rate among households that own their homes, which, at 28.9%, is the third-highest rate in the country behind Hawaii and California. This is likely due—in part—to New Jersey’s notoriously high property taxes. New Jersey’s median real estate tax bill of $8,432 is the highest in the country by a wide margin and one-third higher than second-place Connecticut ($6,004). In New Jersey, homeownership is not necessarily a reliable hedge against rising housing costs, because of the potential to face rising property tax bills.

Moving Out of State

Given New Jersey’s high housing costs, some younger people seeking to form their own households simply choose to leave the state entirely. In 2017, New Jersey Future found that 22-to-34-year-olds (an age range then consisting entirely of members of the Millennial generation) were moving to compact, walkable towns (consistent with the national media narrative at the time), but that Millennials also appeared to be leaving the state in large numbers. A subsequent 2018 analysis confirmed that Millennials were indeed underrepresented in New Jersey’s population, compared to their share of the population nationwide, raising the question of where New Jersey’s “missing Millennials” had gone. Further research into the destinations of New Jersey’s out-migrating Millennials suggested that many of them were relocating to other parts of the country where they could find the walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods they were looking for, but where they could actually afford to buy or rent a home.

Constraints on Supply and Induced Demand

What can New Jersey do to bring down the costs of housing so that young people can afford to live near where they grew up if they so desire? A seemingly obvious solution is to increase the supply of the kinds of housing younger households are looking for, in the kinds of places where they want to live. But this is easier said than done; housing markets are constrained both by a finite supply of land and by government regulation in the form of local zoning. Additionally, many markets in New Jersey have such high demand that increasing supply will not realistically reduce housing prices, and in some cases will actually induce further demand. Would-be suppliers (i.e., residential developers) may have a sense of what kind of housing the market wants, but they may not be able to build it fast enough or build it in the right places, because local zoning prevents them from doing so. And when they are able to build it, induced demand can simply push prices higher.

Building new homes in the right places is an important part of the solution. Today’s young adults don’t want the suburban tract home at the end of the cul-de-sac that characterized their parents’ generation. They want walkable neighborhoods and traditional downtowns where they don’t need to drive 3 miles every time they leave the house. And they want other housing options besides a single-family detached home on a big lot, like townhouses, duplexes, small apartment buildings, apartments above stores, and smaller single-family homes–options that were once common but are now sometimes referred to as the “missing middle” between single-family detached homes and large apartment complexes. Even older Millennials who may have lived in the “city” when they were younger but are now looking for a bit more space are not moving to the same kinds of “suburbs” as previous generations and are instead gravitating toward smaller centers.

Removing Barriers and Building in Affordability

The good news is that New Jersey already contains many smaller cities, walkable suburban downtowns, and transit-adjacent neighborhoods that offer the live-work-shop-play balance that many younger households (and aspiring future households) are seeking. Oftentimes these places do not contain an adequate supply of smaller units that are relatively more affordable than their larger counterparts. The question is how to start producing more housing in these places of the sizes and types that prospective buyers and renters want. This generally means removing barriers to the production of these housing types so that suppliers are free to try to catch up with demand while simultaneously looking to build in more permanent affordability for lower income residents. Steps New Jersey can pursue (and which some other states, counties, and cities are already pursuing) include:

- Accessory dwelling units: Allow the creation of accessory dwelling units (ADUs) (e.g., in-law suites, above-garage apartments, etc.) on single-family lots as-of-right. Los Angeles County offers an example, having recently modified its ordinances to make the creation of ADUs much easier. AARP has developed a model ordinance for state and local governments that are interested in pursuing this option. ADUs would also help older residents remain in their communities as they age.

- Zoning reform: Increase the production of “missing middle” housing types by curtailing municipalities’ ability to zone for nothing but single-family detached housing. Removing restrictions on other housing types would free up markets to expand housing options. The city of Minneapolis abolished single-family zoning citywide in 2018, and other cities are considering similar moves; the website Strong Towns provides a good recent review of where this movement is enjoying some success, including a few cities in California. Oregon even took the bold state-level step of passing a law in 2019 that requires all cities with populations of at least 25,000 to allow two-, three-, and four-unit structures, as well as townhouses, in any neighborhood previously zoned only for single-family detached homes. Oregon thus offers a model for state-level action that does not wait for individual cities and towns to loosen zoning on their own.

- Reduce or eliminate parking minimums: One way to make room for more housing is to devote more space to homes and less to car storage. Parking takes up space—and costs money—that could otherwise be devoted to producing more housing units. Reducing parking requirements would likely reduce builders’ construction costs per unit, pulling prices downward. In 2017, Buffalo became the first city to eliminate minimum parking requirements for all new development citywide, which has led to more shared parking and fewer new parking spaces in the densest parts of the city and has allowed some new projects to proceed that might not have been financially viable under the old requirements. The smaller city of Fayetteville, Arkansas actually beat Buffalo to the punch by two years, although it eliminated parking requirements only for commercial development. A bill is working its way through the California legislature that would eliminate parking minimums for new projects located in neighborhoods served by transit. Berkeley has not waited for the state, doing away with parking minimums in almost all residential neighborhoods citywide. Existing surface parking lots also serve as a sort of urban land bank for built-out areas, offering opportunities for infill development and higher-density housing. In New Jersey, Metuchen built the Woodmont Metro at Metuchen Station project on a former commuter surface parking lot, creating new housing options in a town that had been dominated by single-family detached homes and improving its downtown walkability in the process.

- Regionalizing school districts: New Jersey’s public-school landscape is particularly fragmented. It averages 28 school districts per county,2 the most of any state, and averages just under 15,000 residents per school district, well below the national average of 23,344. Such fragmentation results in duplicative costs for administration, buildings, and equipment and drives up the property taxes that fund public education, which in turn drives up overall housing costs. Moving toward more regional school districts would create economies of scale and would likely help bring costs and property taxes down. Increasing the geographic size of school districts would also mitigate competition for taxable property among districts and reduce local government resistance to residential development, clearing the path for developers to build more housing to meet demand.

- Long-term affordability mechanisms: As neighborhoods become more desirable, prices will rise. To help ensure that our most desirable and opportunity-laden communities are available to people of all incomes and races, it is important for towns to proactively remove a percentage of housing from the investor marketplace and keep rents and sale prices affordable for the long-term. This can be accomplished through a number of mechanisms including inclusionary housing development with proper affordability targeting and controls; buying down market rate houses and apartment units and putting in place long-term deed restrictions; and developing long-term ownership structures like nonprofit owned housing complexes and community land trusts.

1This and all subsequent housing and income statistics are from the 2019 one-year American Community Survey unless otherwise indicated.

2Using data from the 2017 Census of Governments

New Jersey Behind the Curve on Broadband Funding

July 19th, 2021 by Kimberley Irby

The coronavirus pandemic highlighted the extent of the digital divide in New Jersey. As we come out of the orders to stay at home, an ongoing issue is incomplete data on internet access, speed, and prices. One suggested solution is to create an office at the state level to coordinate the data collection effort. Beyond this, state level offices can also communicate, coordinate, plan, and fund broadband efforts in general.

The Pew Charitable Trusts has published research showing that efforts to bolster broadband at the state level have been ramping up, likely due to the way the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed gaps in accessibility and has contributed to more reliance on remote work moving forward. These efforts are becoming increasingly prevalent as more states establish dedicated programs to coordinate their broadband initiatives, designate entities to run those programs, and allocate federal funds for pandemic relief to connect those in need.

More recently, Pew has released a database for state broadband programs featuring information about broadband agencies, funding programs, task forces, and offices. The database allows filtering by state on an interactive map. According to the data, New Jersey is one of only ten states that does not currently have some sort of funding mechanism for broadband. Examples of funding mechanisms include state grants and loans for internet service providers, nonprofit utility cooperatives, and local governments. Furthermore, though New Jersey currently has an agency involved in broadband projects and a task force dedicated to broadband issues, it is not one of the 26 states that have a centralized office for broadband projects.

There have been several calls for governments at every level to ensure that every American has access to high-speed internet. As with other types of critical infrastructure, a stable, long-term funding source is essential to ensuring adequate accessibility and quality. While having a centralized broadband office is not yet the norm, having a funding mechanism is now fairly widespread, and it would serve New Jersey well to join the 40 other states that have one. With dedicated funds to support the deployment of high-speed internet, New Jersey could become a model for the rest of the country in guaranteeing broadband for all.

Strategizing from Sussex to Stone Harbor: Water Infrastructure in New Jersey’s Climate Strategy

July 19th, 2021 by Andrew Tabas

Figure 1: The Draft Climate Change Resilience Strategy describes the importance of preparing New Jersey’s drinking water, wastewater, and stormwater infrastructure for the effects of climate change.

When thinking about climate change in New Jersey, it is easy to focus on the most obvious threat: coastal flooding from sea level rise. However, climate change will have a number of effects on New Jersey’s drinking water, wastewater, and stormwater infrastructure as well. The New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection’s Draft Climate Change Resilience Strategy recognizes these issues and is an important first step toward adapting New Jersey’s drinking water, wastewater, and stormwater infrastructure for an uncertain future.

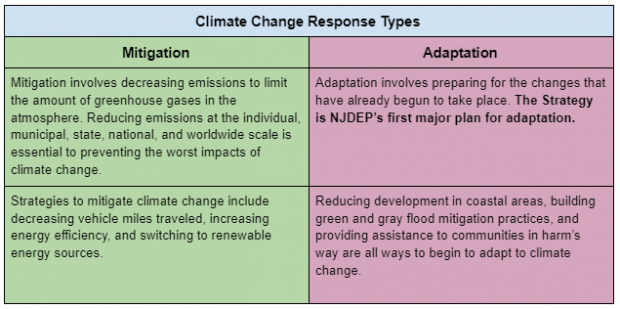

The New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection’s Draft Climate Change Resilience Strategy (“the Strategy”), released on April 22, 2021, is NJDEP’s first major step toward climate change adaptation, as opposed to mitigation. The focus on adaptation makes the Strategy “a critical recognition that climate change is here and will continue to impact our communities for decades to come,” according to New Jersey Future (NJF) Executive Director Pete Kasabach. Figure 2 explains the difference between mitigation and adaptation.

Figure 2: There are two main ways to respond to climate change: mitigation and adaptation. According to NJF Executive Director Pete Kasabach, the Draft Climate Change Resilience Strategy is the State’s first major policy document focused on adaptation.

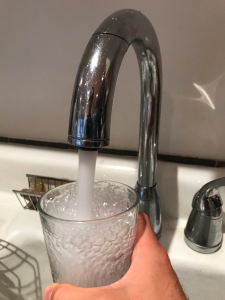

Figure 3: Safe drinking water, which is essential to human health, is at risk due to saltwater intrusion, drought, and more intense storms that could damage infrastructure. Photo credit: Andrew Tabas.

The Strategy highlights several risks to drinking water infrastructure posed by climate change. First, flooding and storms can damage aging infrastructure. Second, current technology and standards were not set up to treat increased salt levels. Third, droughts, increased nonpoint source pollution (e.g., fertilizer runoff from farms), and saltwater intrusion could threaten water supply. To address these issues, New Jersey should invest in its drinking water infrastructure systems. Potential investments include increasing water efficiency, building new water storage, and relocating treatment plants, according to the Environmental Protection Agency’s website on climate impacts on water utilities. In its recommendations for the Strategy, NJF advocates for improved resilience training for drinking water and wastewater utility leaders and asks for more information on water infrastructure in future versions of the Strategy. Ensuring access to safe drinking water, one of the most important environmental justice issues, will protect public health across the state.

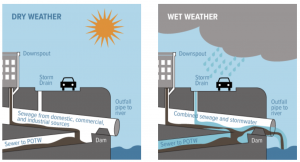

Figure 4: Combined Sewer Systems overflow during heavy rainfall events. Source: US Environmental Protection Agency.

Protecting and improving wastewater infrastructure in the face of climate change is essential as well. The Strategy notes that sewer systems must be elevated and protected from flooding. While this is an important issue, the Strategy does not discuss the risks of increased combined sewer overflows (CSOs). In towns with combined sewer systems, wastewater and stormwater enter the same pipes and are treated at wastewater treatment plants. During intense rain events, the volume in these pipes becomes too much for the treatment system to handle, so the sewage overflows directly into rivers, streets, and homes. As climate change brings more frequent and intense rainstorms, the risk of CSOs will increase. NJF recommends that future versions of the Strategy add a new action to address this issue: “incorporate climate change projections into CSO planning and forthcoming permits.” Smart planning in cities with combined sewer systems can reduce the negative health effects that come from exposure to sewage.

Figure 5: Bioswales and other types of green infrastructure can improve water quality, reduce nuisance flooding, and generate public health benefits. Image credit: AKRF, Inc., 2018.

The Strategy does an excellent job of addressing green infrastructure for stormwater management. Green infrastructure involves the use of practices that mimic the natural water cycle to capture stormwater and allow it to trickle into the ground. The Strategy highlights the benefits of green infrastructure, which include improving water quality, managing nuisance flooding, and improving public health. It is an encouraging sign that the Strategy highlights the importance of green infrastructure and emphasizes that it should be built first in the communities that need it most. NJF recommends three improvements to the Strategy’s treatment of stormwater. First, the Strategy should go beyond discussing the Stormwater Rule changes adopted in March 2020 by offering a preview of additional Stormwater Rule changes anticipated through the New Jersey Protect Against Climate Threats initiative. Second, the Strategy should describe a path forward for the implementation of Complete and Green Streets. Third, the Green Acres open space funding program has a beneficial opportunity to prioritize green infrastructure, as described by Jersey Water Works. These changes to the Strategy will help to bring the benefits of green infrastructure to communities across New Jersey.

Making drinking water, wastewater, and stormwater infrastructure resilient is essential for adapting to climate change. New Jersey’s Draft Climate Change Resilience Strategy offers promising first steps in all three of these areas. Read NJF’s full comments on the Climate Strategy to learn more.

Filling the Missing Middle: Context-Sensitive Design and Development Innovations for Diverse, Sustainable, Walkable Neighborhoods

June 25th, 2021 by Missy Rebovich

Increasing the housing stock in the most densely populated state in the country may seem like a daunting task, but it doesn’t have to be. Panelists Joshua Zinder, managing partner, JZA+D; Keenan Hughes, principal, Phillips, Preiss, Grygiel, Leheny, Hughes LLC; Travis Seal, founder and principal, Select Redevelopment; George Gnad, president and broker of record, Lenders Capital Realty Services; and Michael La Place, planning director, Princeton shared how they resolve the tension between municipalities’ need to grow and residents’ fear of change at the 2021 New Jersey Planning and Redevelopment Conference’s Filling the Missing Middle: Context-Sensitive Design and Development Innovations for Diverse, Sustainable, Walkable Neighborhoods panel.

There has been increasing demand for walkable communities—places where you can live within walking distance of the services and amenities you need, such as Princeton, Montclair, and Summit—and this has only become more apparent during the COVID-19 pandemic, explained Hughes. But, so much demand coupled with insufficient supply has led to skyrocketing home prices. Part of the issue is that the housing stock in these communities consists overwhelmingly of large single-family homes. This means limited options for empty nesters, people looking to downsize, and those who need just a bit more space than bigger cities can offer. Hughes explained that missing middle housing—affordable, multi-family, entry-level stock supporting a range of lifestyles and family types in walkable, sustainable neighborhoods—can fill these gaps by increasing and diversifying the housing stock, while providing other benefits, such as support for local businesses.

One of the most important considerations to assuage concerns about increased density is to ensure that missing middle housing fits within neighborhood contexts. Zinder detailed some of the strategies he implements when developing missing middle housing: adaptive reuse, strategic additions, maximizing property utility, and infill housing. The success of these strategies depends on one common element: ensuring that the finished structure fits within the context of its neighborhood in terms of height, setback, and style. Density doesn’t have to look dense, and it can even help blend transitions from one neighborhood to another, such as the often stark divide between a downtown business district and its adjacent single-family residential zone. Seal emphasized that each project should be evaluated to ensure that it will benefit the neighborhood and reflect its context.

In addition to local resistance to density, zoning codes present a hurdle for developing missing middle housing. La Place suggests that municipalities update their municipal master plans in order to better facilitate the types of development that they already know they want. For example, many towns have new affordable housing requirements. Rather than falling back on multi-family housing zones that tend to be situated off on their own, Princeton created a new overlay zone to incentivize higher density and infill development near the downtown area. Another zoning requirement that municipalities should reconsider is RSIS parking standards, which often impede missing middle development by eating up available developable land. It is critical, La Place said, that stakeholders and leadership work together to identify their community’s goals and implement a plan to achieve them.

Securing financing for missing middle development can be tricky, explained Gnad. Because of the scale of this type of development, larger lenders may not see their value. The key is casting a wide net to catch those lenders looking to flesh out their portfolios with smaller projects. Other financial tools, such as New Markets Tax Credits, may be available for adaptive reuse projects, and the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit is an option if the development meets its requirements.

With the right team in place to plan an appropriate structure, work with the community and its leadership, and navigate the financing process, missing middle housing can be achieved in any community, providing essential housing

Oh, Sweet Relief! Stormwater Utilities as an Equitable Tool to Solve Flooding and Pollution

June 25th, 2021 by Gary Brune

When we discuss the attributes of our favorite communities, chronic flooding or unswimmable lakes and streams do not make the list. However, many municipalities in New Jersey confront those problems and, for at least some of them, the creation of a stormwater utility could be the key to a more sustainable, prosperous future. Similar to traditional water and sewer utilities, stormwater utilities provide a stream of dedicated revenue that is delivered in the most equitable manner, as a user fee. This stable funding ensures a state of good repair across stormwater drainage systems, preventing property damage, protecting public health, and sheltering economies that rely heavily on outdoor recreation.

In this session during the 2021 New Jersey Planning and Redevelopment Conference, co-hosted by New Jersey Future and the New Jersey Chapter of the American Planning Association, four speakers covered the basics of stormwater utilities, including typical program design, fee structures, and credits for stormwater mitigation projects. Bree Callahan, Stormwater Manager at New Jersey Future, recognized the challenges, but noted the rising popularity of such utilities across the country. “In the 10 years from 2009 to 2019, nearly 700 new stormwater utilities were created, an increase of nearly 70 percent. There are over 1,700 such programs in operation today,” she said. (For a comprehensive view, see New Jersey Future’s recently launched resource center at https://stormwaterutilities.njfuture.org/).

Adrienne Vicari, Financial Practice Area Leader with Herbert, Rowland, and Grubic, Inc., and Michael Callahan, Stormwater Program Manager at the Derry Township Municipal Authority (DTMA), jointly reviewed how that Pennsylvania authority established a regional stormwater utility in 2017. Serving 20,000 customers across six municipalities, much of DTMA’s existing stormwater infrastructure (including 31 miles of pipe and 2,500 inlets) dates to the early 1900’s.

Vicari emphasized the importance of public outreach before, during, and after such an initiative. The DTMA first established a Stakeholders Advisory Committee of residents and local officials in 2015 to secure feedback on the community’s vision of the future, the desired level of service, and an equitable fee structure based on “impervious area” (i.e. hard surfaces such as concrete) which prevent rainfall from filtering into the soil, a driving factor for stormwater quantity and quality.) A series of public meetings and a coordinated public education campaign followed.

In outlining the township’s fee approach, Callahan noted how the use of a standard billing unit, the “equivalent residential unit” (ERU), ensured an equitable distribution of the financial burden. This is important because, in many communities, most stormwater runoff is generated by non-residential properties, including parking lots. In DTMA’s service area, one third of the total impervious area is attributable to only 10 parcels. While non-residential properties comprise 11 percent of all water accounts, they represent 73 percent of the billing units based on impervious area.

Account Type Percent of Water Accounts Percent of ERU Billing Units

Non-Residential 11% 73%

Residential 89% 27%

Based on the projected program cost and the number of ERU billing units in the region, the basic fee rate was set at $6.50/month/ERU.The authority employed a tiered fee system: the more impervious area on a property, the higher the monthly cost. (E.g..,The typical residential home is assigned 1 ERU and pays $6.50/month (i.e., $78/annually), while non-residential properties, with higher impervious area, are assigned multiple ERUs and pay a much larger amount.)

Callahan also shared some “lessons learned”

- Actual rate appeals/delinquencies were double what was projected, decreasing revenue.

- Emergency spending on stormwater dropped precipitously (i.e., 80 percent), from an annual average of $300,000 to $60,000 when the program was fully implemented.

- Fee credits were set on a sliding scale, with the highest value (45 percent) provided for green infrastructure projects.

Callahan emphasized, “Project selection should focus not only on the obvious, such as areas of local flooding, but also upstream sources of stormwater, where the problem originates.” (For more information about Derry Township Municipal Utility Authority’s program, see: http://www.dtma.com/our-services/stormwater/stormwater-program-fee/).

Molly Reilly, Water Quality Coordinator for the NJ League of Conservation Voters, rounded out the session by addressing public engagement, including how to manage opposition. Reilly emphasized, “First and foremost, outreach campaigns must be clear on the question, “why is this necessary?” Then, build allies, including trusted community organizations who often carry considerable weight locally. Reilly recommended communication techniques include storytelling (with strong examples drawn from residents’ daily life), powerful photo images (e.g., flooding damage), simplified information (e.g., mapping tools), and the use of a variety of media platforms. Since NJ is the 4th most diverse state in the country, with 45% of its residents identifying as people of color, multi-language materials are vital.

Savvy Stormwater Strategies: How Planning at Every Level Can Help New Jersey Weather the Storm

June 25th, 2021 by Gary Brune

Who could oppose being savvy at something important? And stormwater (i.e., runoff from heavy rain or snowfall that is not absorbed into the ground) is clearly something to take note of — ask anyone who has suffered flood damage or health impacts from polluted water. However, most people are not well versed on the subject, which is why prudent planning is so important to protect the public and sustain healthy communities.

A four-speaker panel, during the session Savvy Stormwater Strategies: How Planning at Every Level Can Help New Jersey Weather the Storm, held at the 2021 New Jersey Planning and Redevelopment Conference co-hosted by New Jersey Future and the New Jersey Chapter of the American Planning Association, explored this issue from a regulatory, research, municipal, and policy standpoint. The session provided practical guidance on strategies to corral runoff and increase resiliency in the face of climate change, and identified important next steps to consider.

In a broad overview of a changing regulatory landscape, Gabe Mahon, Chief of NJDEP’s Bureau of NJPDES Stormwater Permitting and Water Quality Management reviewed the key requirements associated with municipal separate storm sewer system (MS4) permits that govern local drainage networks. Minimum control measures, such as controlling construction site runoff, mapping, pollution prevention, and public education reflect the basic requirements under the Federal Clean Water Act. Local ordinances cover both residential and non-residential projects and must satisfy DEP ‘s respective regulations, including Residential Site Improvement Standards (RSIS, N.J.A.C. 5:21) for major residential development projects as well as stormwater management rules for commercial and industrial uses. (The RSIS streamlines the residential development process by providing one set of standards, thereby reducing costs of building housing and ensuring predictability in the review process.) In certain cases, such as freshwater wetlands and the Coastal Area Facility Review Act (CAFRA), DEP permit regulations apply directly.

NJDEP’s recent amendments to the stormwater management rule set an adoption deadline of March, 2021, however 60 percent of municipalities have yet to secure county approval for their ordinance. Mahon cautioned, “NJDEP is working with counties on this, and localities that have yet to act are encouraged to contact the Department to avoid potential enforcement actions.”

In an important paradigm shift, the new stormwater rule enhances the role for green infrastructure (GI). As opposed to traditional detention basins, which capture and meter out stormwater, often in a way that prolongs the impact of a heavy storm on surrounding waterways and roads, GI projects store, infiltrate, or filter stormwater in place. The result is less stress on surrounding waterways, including reduced flooding, erosion, and scouring. GI also provides important ancillary benefits, such as recharging underground aquifers. (The new GI standards in the updated stormwater rule may be found at NJAC 7:8-5.3). Going forward, detention basins and manufactured treatment devices (MTDs) will require a waiver from NJDEP.

Mahon also noted that amendments to the New Jersey: Protecting Against Climate Threats (NJPACT) program are planned for later in 2021. This will include the use of more recent rainfall projections reflecting 2020 data (i.e., in place of the 2000 baseline), which will help ensure that developments are truly built to last.

Chris Obropta, Extension Specialist at Rutgers Water Resources program, described a study in regional stormwater management planning for the North and South Raritan River. By analyzing an area on a watershed basis, both problems and potential solutions are easier to identify. Large differences in impervious coverage exist across watersheds, and given their interrelationship, well-placed GI investments can amplify benefits to multiple, neighboring localities. At least initially, the fastest approach is to identify GI opportunities in public spaces (e.g., schools, fire houses). GI can reduce impervious area significantly, which is especially important in places with high or medium density and commercial activity where it commonly ranges from 17% to 21%.

Michael Stanzilis, Mayor of Mount Arlington outlined the cultural shift that is necessary for municipalities to ensure their sustainability . The creation of a local advisory “Green Team”, a comprehensive review of the local stormwater management code and related ordinances to mesh with DEP regulations, and a GI checklist for developers are good first steps. For example, the latter might include required implementation of rain gardens to offset development. In the mayor’s view, “It is far better to proactively plan for stormwater needs than wait until the next crisis arrives.”

Finally, Ann Heasly, Program Manager for Policy and Planning at Sustainable New Jersey, described how public recognition of good deeds can help prompt others to act. Presently, 81% of New Jersey towns participate in Sustainable New Jersey’s certification program, representing nearly 90% of the state population, and 45% of those towns are certified as “sustainable”. Certification, which is voluntary and free, identifies participating municipalities as leaders in areas such as land use and transportation planning (e.g., bike and pedestrian pathways.) Beyond tangible benefits such as cost savings (e.g., energy efficiency) and access to grants and expert advice, certified localities see progress on what is most important: building to a better future.

Ensuring Equity in Transit-Oriented Development

June 25th, 2021 by Tim Evans

State leaders are embracing the concept of transit-oriented development (TOD), which encourages residential and commercial development to locate within walking distance of public transit stations, enabling residents to complete some or all of their trips without a car. The private sector also recognizes the demand for housing in transit-accessible towns. But with transit-adjacent neighborhoods being a limited commodity, how do we make sure the option of living near transit is available to everyone?

The Ensuring Equity in Transit-Oriented Development session examined population patterns with respect to race and income around New Jersey’s transit stations. This session was built around a report, Ensuring Equity in TOD: A Blueprint for State-Level Reform in New Jersey, prepared by a policy workshop class at Princeton University under David Kinsey, Visiting Lecturer in Public and International Affairs, and with New Jersey Future and the Fair Share Housing Center as clients. Kinsey moderated this 2021 New Jersey Planning and Redevelopment Conference session, and the speakers included Wendy Gomez and Alex Merchant, two of the students from the class; Nat Bottigheimer, New Jersey Director at the Regional Plan Association; Eric Dobson, Deputy Director of the Fair Share Housing Center; and Tim Evans, Director of Research at New Jersey Future.

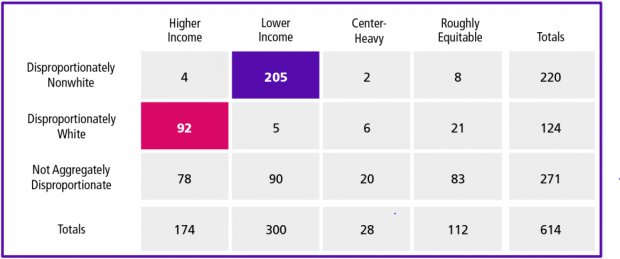

Striking differences in racial and economic equity and opportunity characterize the neighborhoods surrounding New Jersey’s 244 transit stations. Among 614 census tracts that are within a half-mile of one or more transit stations, 205–a full one-third–are both disproportionately nonwhite and disproportionately low-income. Meanwhile, another 92 tracts are both disproportionately white and disproportionately upper-income. Only 83 tracts roughly resembled statewide population distributions with respect to both race and income. In other words, New Jersey’s transit stations, as a whole, display an alarming degree of segregation by race and income, indicating significant room for improvement in terms of equity.

The Princeton students discussed several policy changes suggested by the class that might enable state agencies to address questions of equitable access to transit. They recommend that the Housing and Mortgage Finance Agency make changes to its criteria (known as the Qualified Allocation Plan, or QAP) for awarding credits in the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program in ways that would steer new lower-income housing into transit station areas in which lower-income households are underrepresented, while avoiding station areas where such households are already concentrated.

The class recommends that New Jersey Transit’s recently-created Real Estate, Economic Development and Transit Oriented Development office establish an affordable housing policy for joint development projects to ensure that affordable housing is part of any new development that happens on station-area land owned by NJ Transit. Dobson pointed out that, by not having such a policy, NJ Transit is currently in violation of the Fair Housing Act, which requires any development on state-owned property to have an inclusionary housing component.

The class recommends that the New Jersey Department of Transportation’s Transit Village program require affordable housing planning for a municipality to qualify as a Transit Village. Evans mentioned that the program is currently opt-in, but that New Jersey Future would like to see NJDOT promote the program more proactively. Furthermore, Evans agreed that creating opportunities for affordable housing in station areas should be part of the criteria.

The students indicated that the station-area tracts in which racial and income profiles most closely resembled those of the state also tended to have the most diverse arrays of housing options, enabling households across the income spectrum to afford to live near transit. (Because of the strong correlation between race and income, greater income diversity also usually results in greater racial diversity.) The panelists agreed that this points to housing diversity as an important contributor to more equitable outcomes in station areas and that zoning reform is needed in order to foster a wider variety of housing types. The class suggests that the legislature create an “unmet need TOD zoning overlay” that would allow developers to build mixed-income housing with an affordable set-aside in transit-adjacent tracts in any municipality having an outstanding Mount Laurel affordable-housing obligation.

The panelists agreed that New Jersey should follow the lead of cities like Chicago, Los Angeles, and Minneapolis, as well as states like Massachusetts and Oregon. These cities and states have recently enacted some form of zoning reform designed to increase the variety of housing in certain places, whether it be prohibiting single-family-only zoning, creating as-of-right upzoning in transit station areas, or allowing developers of affordable housing to override local zoning. Gomez mentioned that Los Angeles incorporated an equitable TOD policy in 2016 that has nearly doubled the supply of affordable housing near transit.

Given the importance of TOD in attracting younger people who want to live in compact, walkable neighborhoods, as well as the role of increasing transit ridership in helping the state meet its greenhouse gas reduction goals, state leadership is critical in ensuring that the benefits of living near transit are made available to everyone, regardless of race or income.

Municipal Approach to Racial and Economic Inclusion

June 25th, 2021 by Sherry Hicks

In a session entitled Municipal Approach to Racial and Economic Inclusion at the 2021 New Jersey Planning & Redevelopment Conference held in June and co-hosted by New Jersey Future and the New Jersey Chapter of the American Planning Association, elected officials explored what can be done to foster more racial and economic inclusion in planning and redevelopment.

Barbara George Johnson, vice president, John S. Watson Institute for Urban Policy and Research Kean University moderated the session, which included President and CEO of the National Urban League Marc Morial, and panelists Vernon Mayor Howard Burrell, Paterson Mayor Andre Sayegh, and Willingboro Mayor Tiffani Worthy.

Morial, a leading voice on the national stage for the battle for jobs, education, housing, and voting rights—and no stranger to the needs of municipalities, especially urban municipalities in New Jersey—explained that planners have immense influence and power; impacting where trees are planted, where schools are located, what street signs look like, the parameter and style and the design of houses, and how municipalities and towns think about many important and challenging issues.

“For the planning discipline—just like any of us who work on urban affairs, cities, townships, towns, villages anywhere in the United States of America—we are at that point where the challenge is how do we think about the discipline of planning through an equity lense,” stated Morial.

He urged planners to think about equity as America is reshaped demographically, such as aging Americans, changing households, and family dynamics that are moving away from what was thought of as the traditional nuclear family.

He also encouraged planners to be mindful of growing wealth inequalities, which manifest from fundamental issues of poverty and homeownership. He pointed to the Black homeownership rate being as low as it was the year the Fair Housing Act was passed in 1968.

He suggested that every community needs an affordability planning strategy and an affordable housing policy, and be insistent on their execution. “As we think about how to remake the city, we have to think about it from an affordability and a quality of life standpoint. Affordable housing strategies should include amenities, such as parks, playgrounds, broadband, and small businesses.”

Mayor Worthy shared the history of Willingboro, one of the oldest townships in New Jersey, and its economic justice challenges during its development and growth from the 1950s to the 1970s, due in large part to the development of Levittown, a community with deed-restricted racial covenants.

As a result, in the 1960s the township was sued for discriminatory practices, and in the 1970s, white flight negatively impacted the community. Today, Willingboro is a predominately Black and brown community of over 33,000 residents from all over the world.

“We have a lofty vision and have been working on updating our master plan, along with a strategic plan to attract developers to create a destination location,” she said. “We are working to overcome a lot of assumptions about our population.”

Worthy looks forward to continued partnerships with developers, residents, and elected officials at every level of government to be able to create the Willingboro we all want to experience.

Vernon Mayor Burrell shared how his experiences growing up in the Deep South prepared him for life and leadership in a predominately white, rural community in northern New Jersey.

Vernon Township is located in one of the most conservative counties in New Jersey, Sussex County. It is 85% white, 9% Hispanic, and 4% Black.

“This socio-economic makeup of my town represents its own unique challenges and opportunities to manage and neutralize any racial, economic, and political impediments,” said Burrell. “But, I can tell you this as an individual who has lived in Vernon Township for the past forty-one years, there are certain indicators that lead me to believe that we are doing OK.”

Burrell pointed to an anti-racism march organized last year by a young white resident. He also noted that over the past six months, the Covid-19 virus has driven a significant number of mostly urban residents to Vernon Township, many of which are people of color. He and the Vernon Township Council have joined together to ensure that these individuals know that their township wants and needs them to become fully included.

Paterson Mayor Sayegh shared that the city’s rich history of diversity can be traced back to it’s days as a hub for immigrants who came in waves from either South America or the American South. Founded by Alexander Hamilton, it is the third largest city in the state and the first planned industrial city in the U.S. It was recently designated the most diverse city in the state by the Star-Ledger.

“We’re proud of that designation. But we’ve had struggles,” said Sayegh, noting the challenges Paterson and other cities in the state faced in the 1960s.

Disinvestment of money and white flight to the suburbs made it hard for Patterson to recover. Sayegh pointed to what Paterson is doing today. “One of our signature economic development projects is the restoration of Hinchliffe Stadium. One of only two stadiums in the United States that hosted Negro League games,” he said. “We have affordable housing projects like the Riverside Village with 200 units set aside for senior citizens and low-income families.”

A partnership with a nonprofit organization and the local hospital will result in 56 units near the hospital with units set-aside for individuals with special needs and addressing the issue of community members using the emergency room as shelter. Additional projects include, the Guaranteed Income Initiative and the Financial Empowerment Center, and a license-restoration program launching soon to help residents get their driver’s license back and become gainfully employed.

Panelists agreed that urban revitalization needs to focus on racial and economic inclusion strategies to avoid the policies and practices of the past.

“I think in the public interest today is economic equity and inclusion and thinking through what the policy looks like, how you approach it in an intelligent, transparent way,” said Morial. “ If we can’t create in revitalization, economic participation and inclusion, then what we are doing is repeating the urban Negro removal policies of 40, 50, 60 years ago.”

Advised Morial, “A wise person changes, a fool never learns. Take the lessons and listen. Let’s do it differently, and by doing it differently, we can do it better.”