New Jersey Future Blog

More Than Mailers: Keys to Effective Outreach and Communication for Lead Service Line Replacement (LSLR) in New Jersey Communities

April 1st, 2025 by New Jersey Future staff

By Deandrah Cameron, Policy Manager, and Ben Dziobek, Community Outreach Specialist

New Jersey Future’s Funding Navigator team has developed expertise in supporting water systems and municipal leaders in navigating the complexities of lead service line replacement (LSLR) funding, outreach, and communication. Meanwhile, the Jersey Water Works Lead Service Line Implementation Work Group and Lead-Free New Jersey address the technical and logistical aspects of LSLR. Effective communication and community outreach are critical aspects of a successful LSLR program. In this blog, we’ll highlight key strategies and best practices for communication and outreach that can improve participation rates and build customer trust.

Stakeholder Engagement and Education

A successful LSLR program requires a drinking water system to effectively communicate with customers, municipal leaders, community advocates, property owners, and occupants at every step in the replacement process, from inspection to post-replacement sampling. Lead affects the nervous system, and the impact can sometimes be hard to quantify and invisible. Customers may not understand the health implications if a lead service line serves their home or the importance of cooperating with inspections to determine the status of their service line, which could be a lead, copper, galvanized, or even a lead-lined galvanized pipe. Moreover, since water systems in New Jersey were not previously responsible for the customer portion of the line, service line inventories are mostly incomplete, and the service line composition is likely to be unknown. Communicating to residents about pending service line inspections and/or removal is crucial to increasing participation and consent, particularly regarding the customer-owned portion of a lead service line.

Effective and early communication ensures residents’ trust and confidence in the water system. As we’ve seen in crises like Flint, Michigan, or Newark, New Jersey, when there’s a high level of concern regarding lead in drinking water, customers may lose trust in the water system if key information is not relayed promptly. Drinking water systems need to educate customers, elected officials, and key stakeholders in a manner that empowers customers and key officials to take action. Beyond initial outreach, water systems should continue building trust and maintaining engagement through frequent, transparent, and consistent messaging.

Strategic Messaging and Outreach Campaigns

Direct communication in the customer’s preferred channel or method of communication is essential for consideration. Both paying and non-paying customers need to be informed about the risks associated with lead contamination, the benefits of LSLR, and the steps to ensure their waters’ safety. Direct communication through preferred channels helps build trust, address concerns, and encourage participation in the replacement process. Water systems must consider adapting their outreach strategies, which could differ across service areas, especially for systems serving multiple municipalities.

Thorough research and review of prior campaigns are necessary to increase the impact of outreach campaigns. Understanding lessons learned such as those shared in this new report, as well as identifying best practices, and assessing the success of different communication channels, can help refine strategies and improve customer engagement. Incorporating key service area demographics and preferred communication trends enables water systems to leverage these insights to improve future outreach efforts and meet communication targets. Engaging hard-to-reach populations is crucial in LSLR outreach campaigns. Certain population groups, based on culture, language barriers, location, or socioeconomic status, may lack access to or utilize different means of communication that don’t fit the general patterns the service area uses. For instance, some individuals may not use social media, have internet access, or speak the dominant language of the service area, making it challenging for them to receive critical information about LSLR. To effectively engage these populations, water systems must develop specialized outreach campaigns that cater to those unique needs and communication barriers.

In Atlantic City, the Funding Navigator team has taken a different approach to increasing response rates for lead service line identification by strategically designing mailers in multiple languages. Recognizing that regulatory lead notices often go overlooked, we combined them with a more visually engaging self-reporting form in a single mailing. By using bold colors as a visual cue for urgency and ensuring the materials were accessible to diverse communities, we made it easier for residents to understand the importance of checking their service lines and taking action. This “two-for-one” approach maximized efficiency—ensuring compliance while driving more participation in the self-reporting process.

Hard to Reach Populations

The importance of targeted outreach to hard-to-reach populations cannot be overstated, as lead exposure poses a significant public health risk. Identifying these populations and creating a tailored approach to delivering health education and replacement services is essential. This may involve partnering with community-based organizations, using culturally sensitive messaging, providing multilingual support, or leveraging alternative communication channels such as print media, community events, or door-to-door outreach. These proactive steps champion an inclusive approach to outreach. This way, water systems can ensure that all residents, regardless of their background or circumstances, receive the information and support they need to stay safe from lead contamination.

Well-established community groups play an essential role in disseminating information on local issues. They may cut across different population groups, including older people and immigrants who face language barriers. Building partnerships with organizations connected to hard-to-reach populations is crucial, enabling information delivery to individuals already within their network, fostering trust, and encouraging participation. The importance of partnership becomes especially instrumental for programs utilizing customer surveys to improve inventories. Additionally, employing a variety of delivery methods for information is crucial.

Effective Communication Methods

Door-to-door canvassing, for instance, allows for personalized interaction and can be particularly effective in reaching residents who may not have access to digital platforms. Choosing the right “messenger” is necessary to open the doors. Drinking water systems should think critically about partnering with community leaders and groups valued as trusted messengers and, most importantly, members of the communities they serve. Even so, other delivery methods offer distinct benefits, such as social media announcements, presentations, door hangers, flyers, posters, T-shirts, ads, and billboards. Social media announcements, for example, can rapidly disseminate information to a large audience, while visuals can enhance the message and capture attention. Town halls provide an opportunity for in-depth discussion and Q&A sessions. Multilingual door hangers, flyers, and posters offer a tangible, offline presence, while T-shirts and ads can serve as conversation starters. Billboards provide high-visibility messaging. By leveraging multiple delivery methods, community organizations can ensure their message reaches the widest possible audience, encouraging participation and driving engagement. Utilizing community surveys to prompt customers to self-identify lead service lines is a great way to educate consumers and accelerate lead service line inventories. Customer surveys may supplement traditional methods and prove particularly useful where there are challenges in accessing private property for lead service line inspections and replacements, such as rental units. Additionally, to maximize participation, consumers typically require instructional information on visually inspecting a service line or performing scratch tests. Community meetings are a great way to conduct such training and educational outreach.

New Brunswick: A Case Study in Community-Led Mapping

In New Brunswick, we’ve seen firsthand how student-led mapping initiatives can play a crucial role in addressing the challenges of lead service line replacement. Ensuring accurate service line inventories has been a persistent issue with so many rental properties and off-campus housing units. Many landlords and tenants were unaware of their pipe materials or hesitant to engage with municipal authorities.

To bridge this gap, NJDEP’s Watershed Ambassador Program, along with student volunteers from Rutgers University, in partnership with NJF’s Funding Navigator team and New Brunswick Municipal Utilities Authority (NBMUA), are taking the lead to begin conducting door-to-door outreach, surveying properties, and helping to identify and document lead pipes in these high-risk areas. Using simple tools like visual inspections and in-person resident surveys, students will collect crucial data that has the potential to accelerate data collection and foster deeper public trust.

Beyond mapping, the initiative also is an opportunity for education. Students are informing others of the risks of lead exposure, and helping residents understand the lead service line replacement process by connecting them with available resources. Their involvement has shown that when local communities, educational institutions, and advocacy groups collaborate, we can overcome barriers to participation and ensure that no household is left out of the replacement effort. With successful partnerships in New Brunswick, the Funding Navigator team is also working to expand this model to Stockton University Atlantic City.

Closing

Ensuring the success of lead service line replacement efforts requires more than just technical solutions—it demands strong community engagement, clear communication, transparency, and a commitment to equity. By learning from case studies like New Brunswick, where student involvement is helping to bridge gaps in data and outreach, and Atlantic City, where strategic, multilingual mailers increased self-reporting, municipalities can develop more effective, people-centered approaches. As New Jersey moves closer to its goal of replacing all lead pipes, the role of communities in shaping and supporting these efforts remains essential.

Breaking the Barrier to Water Infrastructure Funding

March 14th, 2025 by Jessika Sherman

The New Jersey Clean Water and Drinking Water State Revolving Funds (SRF) are critical financial resources that can provide a variety of funding and financing options, including principal forgiveness and low-interest loans, to support water infrastructure improvements across the state. These programs, established through federal and state partnerships, empower municipalities and drinking water and sewer systems to address essential projects, including wastewater treatment, stormwater, and drinking water initiatives. Through affordable financing and principal forgiveness, the SRFs enable communities to invest in crucial water infrastructure upgrades that improve public health and create resiliency to future challenges. These SRF programs have been largely successful. However, there are equity concerns regarding the types of communities that have been more successful in accessing this funding.

Funding doesn’t automatically reach the municipalities and water systems that need it, each system must navigate a complex application process. Understanding and applying for such a large-scale program can be daunting for small, resource-limited systems. In New Jersey Future’s and the Environmental Policy Innovation Center’s 2023 report, Improving a Program that Works: Recommendations to the New Jersey Water Bank for Advancing Equity, it was found that small communities have received a significantly smaller portion of SRF awards. These systems often face capacity limitations, making it a costly and time-consuming effort to submit a complete SRF application. This process requires performing an inventory analysis, financial analysis, gap analysis, and asset mapping — an intensive undertaking with no guaranteed funding outcome. The planning and design phases alone can cost several million dollars, posing a considerable financial risk for small systems.

Recognizing these barriers through its work with municipal leaders, water system staff, and coalitions, New Jersey Future launched the Funding Navigator program in 2023. This program is the first New Jersey statewide nonprofit initiative dedicated to helping New Jersey’s most underserved communities access water infrastructure funding. The Funding Navigator program supports municipalities and small—to mid-sized water systems by providing guidance throughout the application process, assisting with community outreach initiatives, and providing engineering support.

The Funding Navigator Program also collaborates with the following technical partners:

- New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection

- New Jersey Infrastructure Bank

- Environmental Policy Innovation Center

- Syracuse University Environmental Finance Center

- Moonshot Missions

These partnerships enable the Funding Navigator program to provide technical assistance, such as sewage system collection mapping for asset management plans and lead line inventory services, as well as community outreach services, such as community engagement recommendations, public mailers, public education programs, and other services based on the community or water system’s needs.

The work starts with identifying communities that are underserved and disadvantaged. Typically, these are small systems and communities that meet the NJDEP’s affordability criteria and/or the highest distress scores under the Department of Community Affairs (DCA) municipal revitalization index (MRI). Communities that have not received any SRF funding in the past several years are top priorities. Jersey WaterCheck, an online dashboard that features data about the state’s drinking water, wastewater, and stormwater systems, offers important water system data that also helps us identify clean water systems and drinking water systems with known harmful bacteria, the number of known and unknown lead service lines, and how customer-friendly systems are.

By the end of 2024, The Funding Navigator program grew from 3 towns to partnering with 10 communities across the following eight counties:

By the end of 2024, The Funding Navigator program grew from 3 towns to partnering with 10 communities across the following eight counties:

- Atlantic

- Gloucester

- Hunterdon

- Mercer

- Middlesex

- Monmouth

- Sussex

- Warren

This growth underscores the critical need for targeted support to help municipalities and water systems overcome the challenges of accessing SRF funding. Looking ahead, the Funding Navigator program aims to further strengthen its reach by expanding technical assistance and building deeper relationships with underserved communities. By continuing this work, the program enhances access to critical financial resources and ensures that the SRF programs distribute funding to the communities that need them most.

To learn more about New Jersey Future’s Funding Navigator program, visit the website.

Designing Pedestrian-Friendly Spaces to Enhance Health and Accessibility for New Jersey’s Aging Population

March 13th, 2025 by Bethany Villa

As New Jersey’s population ages, one challenge stands out: how can we create an environment that supports the well-being of older adults, particularly in urban and suburban spaces? The built environment—our streets, sidewalks, and public areas—profoundly affects the health and independence of seniors. Yet many older residents, particularly in underserved communities, face significant barriers to mobility. The key findings from a new report, “The Hidden Impact of the Built Environment: Designing Pedestrian-Friendly Spaces for Enhanced Health and Accessibility for Elderly & Aging Populations in New Jersey,” highlight how New Jersey can design safer, more accessible pedestrian spaces to improve the quality of life for the state’s older adults.

The report reveals that poorly designed urban spaces, especially those that prioritize cars over pedestrians, negatively impact the physical and mental health of older adults. Streets without safe crosswalks, sidewalks, or adequate lighting contribute to physical inactivity, a major risk factor for chronic conditions like diabetes, heart disease, and obesity. Additionally, limited access to parks or social spaces exacerbates feelings of isolation, which can lead to mental health challenges such as depression and anxiety. Conversely, communities with well-designed pedestrian infrastructure promote physical activity, social engagement, and overall well-being, helping older adults maintain their independence for longer.

In response to these issues, the report outlines a series of recommendations for improving New Jersey’s built environment to better support its aging population. First, the state should implement specific guidelines for pedestrian-friendly design that cater to the needs of older adults, ensuring that streets and public areas are safe and navigable. A second proposal is creating a Health Impact Assessment (HIA) tool* to help policymakers evaluate the health outcomes of urban development projects, particularly how they affect seniors. Lastly, the report advocates for a statewide Age-Friendly Communities Initiative,* drawing inspiration from successful local models like Montclair’s efforts to enhance pedestrian infrastructure and increase transportation options for older adults.

By focusing on these strategies, New Jersey can create a more inclusive and supportive environment for its aging population. Improved pedestrian infrastructure and a focus on health outcomes in urban planning will not only benefit seniors but also contribute to a healthier, more vibrant community overall. As the 65+ population in the state continues to grow, now is the time to act—ensuring that New Jersey’s built environment enhances the mobility, independence, and quality of life of its older residents.

*New Jersey Future notes:

- Statewide Age-Friendly Communities Initiative: New Jersey has three robust age-friendly initiatives. Age-Friendly North Jersey and the Age-Friendly State Policy Committee (convened by New Jersey Future) are a connected cross-sectoral network of organizations committed to advancing the Age-Friendly movement across part or all of the Garden State. Lifelong Strong NJ is a third connected advocacy campaign to enlist the next governor as a champion who will ensure all New Jerseyans can thrive in the Garden State as we age.

- Health Impact Assessment: While not official state government policies, Sustainable Jersey, a policy center at The College of New Jersey, has prepared several documents for use by municipal leaders in assessing the aging-friendliness of their town and taking steps to improve conditions for older residents:

- The Complete and Green Streets for All Action focuses on streets and sidewalks and their role in addressing the mobility needs of all users, including older adults.

- The Local Health Assessment and Action Plan is the foundational action for municipalities seeking the Gold Star in Health (an additional recognition the program awards).

- The Community Design for All Ages Action provides several options for municipalities to improve the built environment to accommodate the design needs of older adults.

- The Integrating Health Into Municipal Decision Making Action asks the municipality to complete a Municipal “Health in All Policies” checklist to review internal procedures in municipal operations, as well as a review of a particular policy, program, or plan to assess how health and health equity are being considered in the decision making process.

Bethany Villa, Princeton University Class of 2026, prepared this report as a project for a fall 2024 undergraduate course entitled Critical Perspectives in Global Health Policy, taught by Heather Howard in Princeton’s School of Public and International Affairs (SPIA). Tim Evans, New Jersey Future’s Research Director, served as Bethany’s client and external advisor for the project.

Debt is Not a Bad Word: Funding New Jersey’s Infrastructure through Smart Financing

February 18th, 2025 by Jessika Sherman

The following feature was originally published in the February 2025 edition of NJ Municipalities Magazine, which has been relied upon by local government leaders, department heads and administrators for over 100 years. NJ Municipalities is read by over 6,000 readers each month. You can read an online version, or view the pdf of the print edition.

Municipalities face a tricky balancing act when it comes to infrastructure improvements: they need to address large, costly projects but have limited resources to fund them. Historically, issuing debt has been the primary means that municipalities are left with to finance critical improvements. However, municipal leaders are reluctant to be the ones responsible for issuing debt, while utilities and public systems are often hesitant to raise rates to cover project costs.

The reluctance to take on debt is understandable, especially when debates over the federal debt ceiling and spending often dominate headlines. Concerns over affording the debt service, balancing the budget, raising enough revenues, and not wanting to burden taxpayers or ratepayers are valid. These issues span from the smallest municipalities to the federal government. By assisting municipalities and small-to medium-sized water systems in accessing funding for vital water infrastructure projects, New Jersey Future’s Funding Navigator program has come to appreciate these challenges. While grant programs and federal funding provide some relief, such as the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (aka the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law) and the American Rescue Plan Act, these funds are limited and temporary.

Programs like Clean Water and Drinking Water State Revolving Funds (SRFs) provide municipalities with more accessible options for financing critical infrastructure projects. The New Jersey Water Bank (NJWB), a partnership between the New Jersey Infrastructure Bank (I-Bank) and the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP), offers low-interest loans to support clean water and drinking water infrastructure projects. In addition to the Water Bank, the I-Bank provides low-interest loans for other essential infrastructure through the Transportation Infrastructure Bank and the Resilience Infrastructure Bank. These funding sources are fundamental to addressing the state’s infrastructure needs. When paired with effective planning and sound financial management practices, they help mitigate the risks commonly associated with taking on debt.

“If you set a plan and follow the plan, it helps you avoid an emergency. When you do things in an emergency, you pay more for it and can’t plan as efficiently,” explains Thomas Horn, Executive Director of the Lambertville Municipal Utilities Authority. Horn’s experience highlights the significant potential benefits of State Revolving Fund (SRF) low-interest loans. The municipality utilizes a 30-year infrastructure plan that allows it to anticipate water system needs well in advance. By leveraging low-interest loans from the I-Bank, they have made essential system upgrades while developing a fair and sustainable rate structure to manage the debt service.

Lambertville’s proactive approach helps avoid the high costs and inefficiencies associated with emergency repairs. Horn also acknowledges a perspective shared by many municipal leaders: while no one likes taking on debt, sometimes it is necessary. “It’s like a mortgage,” he says. “Very few systems and towns have the resources to fund large infrastructure improvements outright.” Lambertville’s experience underscores the importance of long-term planning and strategic financing in maintaining critical infrastructure.

Strong financial management practices can help municipalities, utilities, and taxpayers benefit from strategic debt use. For municipalities and utilities, debt provides enhanced project funding by facilitating large-scale infrastructure projects with access to capital markets with favorable interest rates, such as those offered by the Water Bank. As Lambertville has demonstrated, loans provide the financial resources needed for critical improvements without placing an immediate strain on existing funds, enabling municipalities to focus on strategic planning and implementation. This approach ensures that cash reserves are preserved for true emergencies, while a structured repayment schedule spreads costs over time, aligning debt service with the lifespan of the infrastructure. By reducing upfront costs, debt can accelerate project timelines, which is essential for addressing urgent needs.

Even municipalities or utilities with sufficient cash reserves can benefit from debt. Low-interest loans are particularly advantageous when their rates are lower than the returns on cash reserves or fund balances, which can be saved for unexpected delays or misaligned payment schedules. Beyond financial stability, infrastructure improvements driven by strategic debt use make municipalities more competitive by attracting businesses and residents, ultimately strengthening the local economy and increasing ratables, which can help fund the debt service over time.

Taxpayers and ratepayers can also benefit from this approach. Infrastructure investments generate jobs and economic stimulation during the planning and construction phases while offering long-term benefits like modernization and enhanced service reliability. Improved infrastructure leads to better service delivery and greater safety for utilities and water systems. Furthermore, debt payments distribute the cost of these improvements over their useful life, ensuring that future users contribute to funding and avoiding hefty, one-time tax or rate increases. Proper planning, as demonstrated by Lambertville, is critical for avoiding costly and disruptive emergencies and ensuring that communities’ financial and service needs are met effectively.

The reality is that, much like the nation as a whole, New Jersey faces costly and urgent infrastructure challenges. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, addressing all the necessary improvements and repairs for drinking water and clean water infrastructure in New Jersey alone will require an estimated $31.6 billion. In 2021, the U.S. received a C- rating from the Report Card for America’s Infrastructure, while in 2016, New Jersey received a D+ rating, highlighting the dire need for investment. As a coastal state, New Jersey is particularly vulnerable to flooding and the impacts of climate change, making infrastructure improvements and resilience efforts more critical than ever. Debt is not a bad word—it is a vital tool that enables municipalities to address these challenges without overwhelming current resources when used strategically and with sound financial management. By leveraging debt effectively, New Jersey can build the resilient, modern infrastructure needed to support its communities and secure a sustainable future.

Exciting Updates to NJ’s State Plan—Don’t Miss Your Chance to Speak Up!

February 18th, 2025 by Tim Evans

New Jersey Future (NJF) has been a key advocate for the State Plan since our founding in 1987, championing smart growth policies to improve communities and safeguard natural resources. NJF was a member of the consultant team that assisted the Office of Planning Advocacy with the update to the State Plan. I contributed analysis on multiple subject matter areas addressed in the Plan, including parts of the Research Briefs section, Population and Employment Projections section, and the Lasting changes in the post-COVID world section.

- The “Research Briefs” section consists of four subject-matter reports:

- Transit-Oriented Development’s Renaissance in New Jersey

- Young Adults and Walkable Urbanism

- Redevelopment Is the New Normal

- Planning for the Challenges of an Aging New Jersey

- The “Population and Employment Projections” section describes how we evaluated population and employment projections, the issues we examined, and what methodology we decided to adopt. The projections are discussed in the State Planning Commission (SPC) meeting minutes from the 11-6-24 meeting, where the SPC officially adopted the population and employment projections as we recommended.

- The final section of the Population and Employment Projections Appendix, labeled “Lasting changes in the post-COVID world,” highlights some questions that arose during the State Plan update process about changes that were brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic. It is important to watch for which of these changes have staying power and which might revert to their pre-pandemic state since they will have implications for what future growth and development in New Jersey looks like.

NJF remains committed to helping advance the State Plan and ensuring its success across the Garden State, but we can’t do it alone. You can help make the State Plan update a success by providing feedback on the draft plan or joining a public meeting!

Attend one of a series of upcoming public meetings, one in each of New Jersey’s 21 counties. The Salem County meeting happens on February 19, at 5 p.m. and the NJ Highlands Council and Somerset County meetings are February 20. Find more information on these and your county meeting here.

Email (stateplan comments

comments sos

sos nj

nj gov) to submit your comments.

gov) to submit your comments.

Public comments can be submitted at any time during the cross-acceptance process which culminates with the State Planning Commission meeting (anticipated December 2025) at which the vote will take place to adopt the final version of the Plan.

To ensure adequate time for comments to be considered, the Office of Planning Advocacy recommends submitting by April 16, while the county public information meetings are still taking place.

Timeline for Cross-Acceptance Process:

- December 6, 2024: Cross Acceptance commences. Draft Preliminary State Development and Redevelopment Plan released for public comment.

- February 12 to April 16, 2025: Public Information Meetings, one per county. Check the Update to State Development and Redevelopment Plan page in the item about the 2025 County Public Meeting schedule for the latest.

- Spring/Summer 2025:

- Cross Acceptance Reports

- Statements of Agreements and Disagreements

- Negotiation Phase

- State Agency Reports and Responses

- Complete Infrastructure Needs Assessment, Phase II and Impact Assessment

- Summer/Fall 2025:

- Incorporate results of Cross-Acceptance into the Final Draft State Development and Redevelopment Plan

- Hold six (6) Public Hearings (5 virtual and 1 in person)

- Release the Final Draft State Development and Redevelopment Plan

- Winter 2025: State Planning Commission adopts final State Development and Redevelopment Plan

Your voice shapes New Jersey’s future. Share your input by submitting a comment or joining a public meeting.

Breaking Down the State Revolving Fund – Recommendations and Changes

December 2nd, 2024 by Jessika Sherman

This blog is a follow-up to New Jersey Future’s November 2023 report Improving a Program That Works: Recommendations to the New Jersey Water Bank for Advancing Equity. Please see page 1 of the report for a list of acronyms.

Over the next 20 years, the United States must spend $625 billion to fix, maintain, and improve water infrastructure. According to the US Environmental Protection Agency, New Jersey alone will need to spend at least $12,252,800,000 on drinking water infrastructure and $19,352,000,000 on clean water infrastructure over the next 20 years to make all necessary improvements and repairs. The predominant sources of water infrastructure funding and financing for all 50 states are the Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF – wastewater treatment and stormwater management) and the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund (DWSRF – safe and reliable water supply). These State Revolving Funds (SRFs) are financial assistance programs that provide low-interest loans to support critical water infrastructure projects essential for protecting public health and the environment.

The New Jersey Water Bank (NJWB), a partnership of the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) and the New Jersey Infrastructure Bank (I-Bank), manages New Jersey’s State Revolving Funds. NJWB’s financial support to New Jersey wastewater and drinking water systems has generated significant savings through principal forgiveness (PF – grant-like funding) and low-interest loans. Disadvantaged communities (DACs) served by small and medium-sized systems face increased challenges in accessing SRF funding, particularly struggling to reach the initial application stage due to the high costs associated with planning and design. Larger water utilities tend to receive disproportionate awards, while smaller, fiscally distressed DACs lag behind, highlighting a significant equity concern. In Improving a Program that Works: Recommendations to the New Jersey Water Bank for Advancing Equity, released in November 2023, New Jersey Future (NJF) and the Environmental Policy Innovation Center (EPIC) primarily recommended policies to improve access to the SRFs for water systems serving DACs through a more robust method for identifying disadvantaged communities, maximizing pre-construction support, expanding principal forgiveness funds, and providing 0% interest loans.

The New Jersey Water Bank (NJWB), a partnership of the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) and the New Jersey Infrastructure Bank (I-Bank), manages New Jersey’s State Revolving Funds. NJWB’s financial support to New Jersey wastewater and drinking water systems has generated significant savings through principal forgiveness (PF – grant-like funding) and low-interest loans. Disadvantaged communities (DACs) served by small and medium-sized systems face increased challenges in accessing SRF funding, particularly struggling to reach the initial application stage due to the high costs associated with planning and design. Larger water utilities tend to receive disproportionate awards, while smaller, fiscally distressed DACs lag behind, highlighting a significant equity concern. In Improving a Program that Works: Recommendations to the New Jersey Water Bank for Advancing Equity, released in November 2023, New Jersey Future (NJF) and the Environmental Policy Innovation Center (EPIC) primarily recommended policies to improve access to the SRFs for water systems serving DACs through a more robust method for identifying disadvantaged communities, maximizing pre-construction support, expanding principal forgiveness funds, and providing 0% interest loans.

Annually, the NJWB is required to develop Intended Use Plans (IUPs) for the DWSRF and CWSRF, laying out the policies, funding packages, and project priority ranking methodology for the corresponding state fiscal year. Over the last few years, NJF has reviewed New Jersey’s IUP policies and submitted comments concerning the amount of state and federal funding used to address the needs of water systems serving disadvantaged communities. NJDEP, which sets policy for the NJWB, has been open to feedback and working with stakeholders to improve the IUP policies.

Of the ten recommendations made in Improving a Program that Works, NJDEP has implemented the following:

- NJWB has made progress in expanding set-aside activities for technical assistance and support for DACs, particularly for pre-construction needs. Project sponsors who meet the affordability criteria are eligible for the New Jersey Technical Assistance Program (NJTAP), a free technical assistance program for drinking water projects. Additional planning and design grants and principal forgiveness are also available.

- Increased flat caps in all drinking water SRF categories that will result in more subsidies for small water systems, lead service line (LSL) projects, and DAC systems.

- NJWB implemented a tiered funding structure to direct a greater share of financial assistance to DACs with the greatest financial need.

- The most recent IUP clarified the I-Bank’s creditworthiness policy.

NJF is excited to see all the improvements that have been made and hopes to see the following changes made in the future:

- As a key first step in refining its criteria for dispersing principal forgiveness, NJDEP implemented a two-tiered system based primarily on median household income (MHI).To maximize equity, NJDEP should adopt the model established by several other states (e.g., Wisconsin) that incorporates more tiers and indicators (e.g., family poverty, population trend). The combined effect directs a larger share of aid to the state’s neediest communities.

- MHI is still the primary criterion for calculating an affordability score for water systems serving DACs in the Intended Use Plans. NJF and EPIC recommend utilizing the Department of Community Affairs’ Municipal Revitalization Index score, a multidimensional tool comprising ten factors in five broad categories. Alternatively, NJDEP could consider using a water affordability index, such as the one developed by Dan Van Abs (Professor of Practice for Water, Society, and the Environment at Rutgers University, School of Environmental and Biological Sciences) for Jersey Water Works, for distributing funds to those in greatest need.

- NJDEP should significantly expand the use of 0% interest loans to advance critical, high-priority projects in the most distressed DACs. NJDEP only increased these loans for investor-owned systems in the most recent IUP.

- Significantly increase the ranking points awarded in the Project Priority List for “gainsharing” initiatives that benefit both the water utility and the state, such as water affordability programs (which support appropriate rate setting while protecting low-income customers), asset management plans, and regionalization of water assets.

- NJDEP should repurpose a modest portion of loan repayments to increase principal forgiveness to DACs. NJDEP could use this approach to develop a funding source for galvanized water service lines within DACs, which may not be eligible for federal Bipartisan Infrastructure Law funding. Galvanized service lines are required to be removed in NJ by 2031 since they can be a source of lead in drinking water.

- Legislation to improve creditworthiness for severely distressed DACs.

The report also identified the need to address congressionally directed spending, or earmarks. Congress has diverted SRF funding to earmarked projects, and the concern is that earmarked projects circumvent the normal priority-setting process where projects determined to be of the highest priority score the most points. In addition, communities with median household incomes (MHI) above the state average, including some of New Jersey’s wealthiest areas, have received nearly half of the earmarked funds. Meanwhile, less than a third of these funds have gone to disadvantaged communities (DACs). Discussions with New Jersey’s congressional delegation are ongoing, but no definitive changes have been made to prevent federal water infrastructure funding from being derailed by earmarks. Governor Murphy, according to NJDEP, sent a letter to the New Jersey Congressional Delegation expressing concern over this issue.

As last year’s report title states, NJDEP’s CWSRF and DWSRF programs are generally effective and have provided significant funding to improve water systems since their inception; however, as New Jersey faces the daunting challenge of aging water infrastructure and its extreme costs, ensuring equitable access to funding is critical. DACs served by small- to medium-sized water systems face the most barriers to accessing the financial resources needed to repair and upgrade water systems. Though progress has been made, significant disparities remain. NJWB should continue to refine its program to target funding to New Jersey’s most distressed communities, most of which lack the resources to provide safe, reliable water services for the future. Without a greater commitment to both equity and funding, the gap between resource-constrained DACs and other water utilities will continue to grow, undermining efforts to build resilient, sustainable infrastructure across New Jersey.

Sustainable and Cost-Efficient: Implementing a Dig-Once Policy in Trenton

August 30th, 2024 by Samirah Hussain

Lead service line replacement in Newark, New Jersey. Photo by the City of Newark.

Funding, funding, funding–the chorus frequently heard at the inception of almost every community improvement project. Financing remains one of the largest obstacles to infrastructure improvements. The increased frequency and severity of climate disasters and subsequent repair efforts have only exacerbated the issue. The solutions, however, lie in new and innovative approaches to infrastructure development—one such strategy being the dig-once policy.

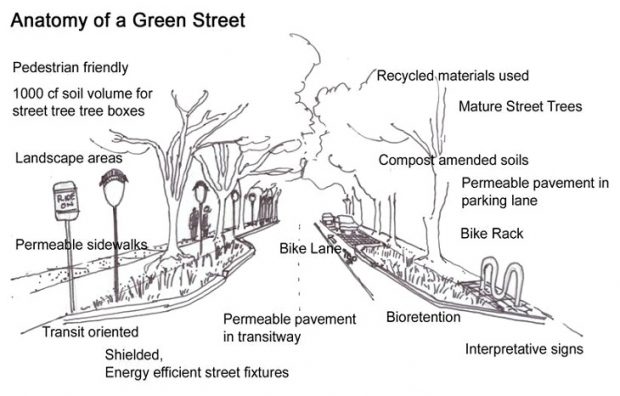

A dig-once policy is a strategy to coordinate major community infrastructure projects to reduce negative environmental effects, construction disruptions, and costs. Some policies may focus on installing new, modernized infrastructure, such as telecommunications, during the excavation phase of major roadway or water projects. Others may focus on coordinating priorities of state agencies, such as the New Jersey Department of Transportation (NJDOT) and the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP), to align investments into major infrastructure improvement projects for mutual benefit. In the case of Trenton, New Jersey, the dig-once policy could serve as an example of a sustainable and cost-efficient method to install green infrastructure alongside the city’s lead service line replacement program.

Trenton: A Case Study

Background

In 2022, the City of Trenton passed an ordinance to establish a Complete and Green Streets policy, which aims to create accessible and safe roads for bicyclists, public transit users, pedestrians, and drivers while incorporating green infrastructure to manage stormwater runoff, reduce air pollution, and more. Since then, the city implemented a wide variety of community engagement, construction, and research projects largely funded by state and federal grants to accomplish the goals in their adopted policy. At the same time, Trenton Water Works, a publicly owned drinking water system, is undertaking a lead service line replacement program in compliance with state legislation mandating the removal of all lead service lines statewide by 2031.

Courtesy of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

In both areas, Trenton has excelled. New Jersey Future’s Managing Green Infrastructure program conducted research to log Complete and Green Streets resolutions or ordinances passed in the Delaware River Basin, as well as Complete and Green Streets projects municipalities took on as a result. Based on this research, the city is one of the leading municipalities in the Delaware River Basin for Complete and Green Streets green infrastructure projects. Since 2017, Trenton Water Works reported that it has already replaced almost 30% of its lead service lines and is currently developing a plan to replace its remaining service lines by 2031.

Despite this success, more work can be done. Trenton Water Works reports it has replaced approximately 10,000 lead service lines already, and estimates there may be up to 20,000 still remaining. Complete streets, tree-lined roads, and rain gardens have been constructed in certain areas throughout Trenton. “Our Streets: A Bike Plan for All” is a community engagement and urban planning project carried out by the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission and City of Trenton, has the goal of establishing complete streets all across Trenton. As of August 2024, the project is still developing its final report, highlighting that the work is nowhere near finished.

Implementing The Policy

Trenton is uniquely positioned to build on its success by implementing a dig-once policy while completing lead service line replacement and installing complete and green streets. Lead service line replacement requires digging up roads, lawns, and green spaces at multiple points in the removal process. Complete and Green Streets projects require repainting roads, installing safety equipment, planting trees and rain gardens, and extending roads. Implementing a dig-once policy would mean contractors for both projects align construction and contractors work collaboratively in the same locations. For example, as contractors dig up asphalt for lead service line replacement, infrastructure for green streets can be installed in the same areas. When the road is repaired and repaved, a complete streets design can be implemented. Having to “dig once” for two different projects saves on construction costs, limits construction disruptions and road closures, and reduces excessive environmental disruptions.

As the state’s capital, Trenton has both the visibility to garner public support for such projects and the duty to act as a role model for other municipalities. With climate-related disasters reaching an all-time high, investing in climate-resilient infrastructure is more pressing than ever.

The difficulty lies in achieving such a high level of coordination between organizations doing unrelated work but aiming for similar improvements to water quality and public safety: Trenton Water Works, the New Jersey Department of Transportation, and the City of Trenton. Technical assistance providers, like New Jersey Future, take the initiative to facilitate the required connections. Moreover, both lead service line replacement and Complete and Green Streets projects require oversight and involvement from overlapping intermediary organizations, like the NJDEP and the NJDOT. These state agencies can utilize their oversight to facilitate coordination between lead service line replacement and Complete and Green Streets projects. With state agencies and municipalities operating on limited budgets, fully funded by taxpayer dollars, coordinated planning on overlapping infrastructure initiatives is in the public’s best interest to save costs.

Closing

Collaboration has the power to make the dig-once policy a reality, saving time, money, and the environment all at once. In the vast majority of townships, the need for infrastructure improvements often exceeds the amount of funding available. Many projects, as is the case in Trenton, are funded with state and federal grants that are limited in quantity and require a township to dedicate additional resources just to apply. A lack of funding, however, does not cause community needs to disappear. Complete and Green Streets are necessary to create healthier, safer, and more comfortable communities resilient to worsening climate disasters. Lead service line replacement is vital to address the life-threatening effects of lead in our community’s drinking water. The dig-once policy offers a strategy to address Trenton’s community needs while saving money and resources. We must rely on innovative solutions to pave a path toward progress—and our state’s capital has the opportunity to lead the way.

Harmful Algal Blooms impacting recreation season for NJ Lakes

July 30th, 2024 by Chris Sotiro

Budd Lake, New Jersey’s largest natural freshwater body, was once an attractive vacation spot in North Jersey during the latter half of the 19th century for sunbathing, swimming, boating, and nearby attractions that have continued to today. Now, Budd Lake faces water quality impairments that threaten the recreation season and associated economic activities. Harmful algal blooms (HABs), caused by the overgrowth of cyanobacteria, have frequently shut down the lake for several weeks during peak summer months. Budd Lake is not just for boaters, anglers, and sportsmen; it serves a vital role in the watershed as the headwaters for the South Branch of the Raritan River, which supplies drinking water to over 1.8 million people living downstream. HABs degrade water quality to the point of toxicity, making this a matter of environmental concern and a public health dilemma. During severe bloom events, most water treatment facilities are not equipped to handle high levels of cyanobacteria and cyanotoxins in source water, putting otherwise healthy residents at risk of adverse health effects.

Harmful Algal Blooms

Human activities enable and exacerbate cyanobacteria growth when favorable environmental conditions are met, such as extreme heat and low flow rates. When nearby residents spray hazardous fertilizers on their lawns or when cars leak oil and grease while passing through US Route 46, those non-point source pollutants can be carried into the lake via stormwater runoff, acting as nutrients for cyanobacteria. Two main sources of nutrients are nitrogen and phosphorus, which can originate from residential, agricultural, or industrial sites, all of which can be found in proximity to Budd Lake. This problem is not confined to Budd Lake alone; major lakes throughout the state have fallen victim to HABs and restricted recreation to protect public health. Spruce Run Recreation Area in Hunterdon County – the third largest reservoir in the state—has already banned swimming for the rest of the summer after a HAB was detected in early July. Once a bloom forms, the affected water can harm humans and disrupt aquatic ecosystems.

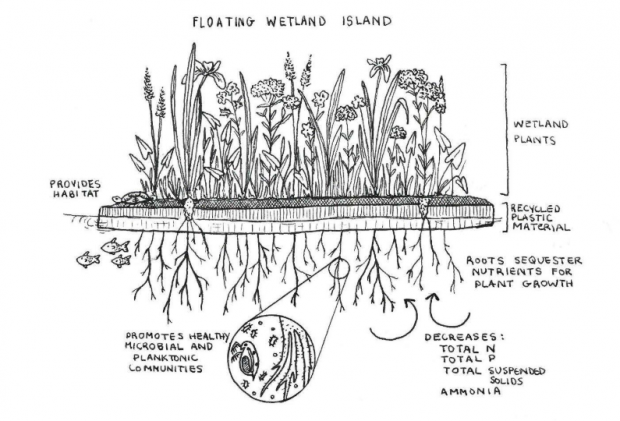

An example of a floating wetland island

Runoff from roadways and nearby neighborhoods is an issue that every municipality must grapple with. Existing gray infrastructure, such as traditional detention basins and pipes, are successful in redirecting stormwater, but fail to filter pollutants out of runoff or prevent contaminants from reaching nearby lakes and streams. While nonpoint source pollution is inevitable, whether or not those pollutants make it into water bodies is a question of effective stormwater planning. Green infrastructure is a low-cost, nature-based solution that sustainably improves water quality, absorbs greenhouse gas emissions, and provides new habitats for aquatic life. In the case of Budd Lake, floating wetlands are a form of green infrastructure that is being deployed to combat HABs by filtering nutrients from runoff that float at the water’s surface.

This illustration, sketched by Ivy Babson of Princeton Hydro, conveys the functionality of a floating wetland island.

Similar green infrastructure projects, such as rain gardens, porous pavement, and bioswales, can be retroactively installed on nearby properties to absorb stormwater and filter pollutants before they can discharge into Budd Lake. New Jersey Future’s Stormwater Retrofit Guide outlines best management practices for installing green infrastructure projects and methods to identify potential retrofit areas. This guide also showcases success stories of stormwater retrofit projects that have improved the health of watersheds throughout the State, such as those in Franklin and Lakewood Townships.

Stormwater basin retrofit in Franklin Township

Cleaning up Budd Lake will take years of collaborative, multi-agency effort. To combat HABs throughout the Garden State, $13.5 million in state and federal funding was made available for municipalities by Governor Murphy in 2019 for evaluation, treatment, prevention, and upgrades to sewer and stormwater systems. This funding, along with grant support from the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP), allowed the Raritan Headwaters Association, Rutgers Cooperative Extension Water Resource Program, and Mount Olive Township to draft a watershed restoration and protection plan. This plan will improve Budd Lake’s water quality by incorporating green infrastructure at strategic sites around the lake to capture and filter large volumes of stormwater runoff.

As HABs have been occurring more frequently in recent years due to overdevelopment and steadily increasing annual precipitation rates, there is a growing need to curtail the use of environmentally harmful products while implementing nature-based solutions to mitigate the discharge of pollutants into major water bodies. New Jersey is the most densely populated state in the country, making it highly susceptible to pollution from stormwater runoff around residential, industrial, and commercial development. As of January 1, 2023, every municipality in the State must comply with new updates to the MS4 Tier A Permit, including the requirement to develop a long-term Watershed Improvement Plan, which must be finalized by the end of 2027. As municipalities draft this Plan in the coming years, it is crucial to explore opportunities to incorporate green infrastructure as a preventative measure that can capture, absorb, and filter runoff to prevent the growth of HABs at beloved community recreation sites and to safeguard water quality.

Heat, Air Quality, and Hope: Community Research and Resilience in Elizabeth, NJ

July 30th, 2024 by Sabrina Rodriguez-Vicenty

Famartin, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia CommonsFamartin

Elizabeth is nestled on the shore of Newark Bay in Union County, a dense, urban enclave in the heart of the Meadowlands estuary and wetlands. Our neighbors include: the Newark Liberty International Airport, where planes fly by my apartment multiple times a day creating noise nuisance. The Port Newark–Elizabeth Marine Terminal, the third-busiest container port in North America, and principal facility for goods entering and leaving the Northeastern United States. The Bayway Refinery, a petrochemical complex in operation since 1908 that produces gasoline, diesel fuel, jet fuel, propane, and heating oil. And Exit 13 of the NJ Turnpike, where every day a quarter of a million cars and trucks emit carbon dioxide and release tire particulate matter into the nearby community. Needless to say, Elizabeth has the qualifications to be classified as an environmental justice community by the EPA, and as one of the most polluted municipalities in the nation is recognized by the state as an environmentally overburdened community.

I was born and raised in Puerto Rico, a small Caribbean island rich in natural resources that suffers from environmental issues like flooding, hurricanes, heat islands, and lacks autonomy and representation, and therefore financial resources for disaster recovery and mitigation. Two years ago, I moved from Puerto Rico to Elizabeth, to attend Rutgers University to study public policy. When I opened my mailbox for the first time in my new home I was greeted by a startling welcome — I received a postcard for a class action lawsuit, which read: “If you’ve lived in Elizabeth or Linden for 10+ years, you may be eligible for compensation regarding environmental hazards.”

“Elizabeth, New Jersey was part of a nationwide study of five cities where all of the maps showed the same stories, that redline areas were prone to heat and flooding issues as well as air quality, which raised asthma rates and health conditions for its residents,” John Evangelista, Ground Works Elizabeth. As a minority woman of color, it seems that, at least for me, there is no escaping environmentally overburdened places to live, or is there?

The panelists of the 2024 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference session “Beating the Heat and Bad Air in Elizabeth, New Jersey” contributed a variety of experiences and deep firsthand knowledge that suggests there is reason for optimism. The session moderator was Clinton Andrews from Rutgers University, who led a community-based participatory research study funded by the National Science Foundation and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to better understand heat and pollution effects in Elizabeth. Other panelists included Carmen Rosario, a Master’s in City and Regional Planning student from the Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Policy, and Jennifer Senick, Senior Executive Director of the Center for Urban Policy Research both at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, and Ground Works Elizabeth’s Deputy Director John Evangelista.

Rutgers’ research goal was to monitor the impact of heat exposure both outdoors and indoors in select Elizabeth Housing Authority (HACE) sites. Affordable housing locations include greater vulnerable populations like seniors and people with asthma, among residents with other health conditions. The study uses sensors and micronets to achieve a smart city paradigm that raises awareness to environmental stressors, enables greater community-level advocacy, and builds citizenship engagement. For the outdoor portion of the study, they installed sixteen sensors around HACE sites, a step that should be implemented in other EJ EPA communities. For the second portion of the study, connections were established between indoor and outdoor air quality using personal exposure measurement devices to identify how personally folks are exposed to environmental stressors, such as indoor smoking, cooking and cleaning choices, and (frighteningly) opening windows.

See page for author, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Key partners:

This research brought together two key partners. The Bloustein microclimate class helped in identifying, through geospatial analysis, community asset maps that included: hospitals, cooling stations, adult day centers, senior citizen centers, libraries, and food pantries. Students also identified policy adjustments for community health, and infrastructure focus to mitigate risks. The second partner was Groundwork Elizabeth, a community-based organization that has worked for over twelve years to develop public health and environmental programs for Elizabeth. Recently, Groundwork Elizabeth launched the Climate Safe Neighborhoods Initiative, a community-based task force advocating municipal policies to mitigate climate change impacts.

Lessons learned:

There were many various stakeholders in the project, each with their own needs. Researchers quickly identified the need to create a customized user experience for the community members. The project used community engagement in system design, including product design—hearing and listening sessions and brainstorming workshops—to answer varied demands. As Elizabeth has a predominantly Hispanic population, it was important to meet the community in their community centers, translate to Spanish, and provide multilingual engagement sessions. The student researchers and future planners learned the importance of conciseness when presenting findings by using relatable language. Another lesson learned is that developing connections and trust requires time. It is not possible to drop sensors into a community by parachute; Groundwork Elizabeth’s more than a decade of community involvement work, along with related relationships, all contributed to the project’s growth and development.

There are troubling connections between race-based housing segregation and climate change. Those who have contributed the least will pay the most. With increasing technological advances and accessibility to micronets and sensors, the hope is that this study is replicated in other environmentally overburdened communities. Although the model requires expertise, deep engagement, and grant support, it’s transferable and replicable across New Jersey and the nation. It is important to use socio-ecological systems framework to connect social and natural sciences; which can identify solutions to complex challenges like heat exposure and find diverse partners to solve them. It is imperative to continue research and present findings to communities that suffer from environmental hazards, so they can make informed decisions about their health.