New Jersey Future Blog

Zero-Vehicle Households and Transit

September 1st, 2011 by Tim Evans

Pedestrians in front of the new 8th Street Hudson-Bergen Light Rail station in Bayonne. The station does not have a parking lot. Image source: Electric Railroaders’ Association, Inc.

A new Brookings Institution study, Transit Access and Zero-Vehicle Households, takes a look at how well (or poorly) various metropolitan areas’ public transit systems are serving transit-dependent populations – that is, households that do not own cars.

The New York and Philadelphia metros, which together contain most of New Jersey’s population, do very well: New York ranks third and Philadelphia 16th among the 100 largest metro areas by population, in terms of the percent of their zero-vehicle households that have access to transit. (Honolulu and — surprisingly — Los Angeles rank first and second, respectively.) Atlanta, Houston and Dallas rank in the 70s and 80s, the poorest-performing large cities; most of the similarly low-ranked metros are smaller ones with limited public transportation.

Just seven big metro areas together account for more than half the nation’s zero-vehicle households: New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Boston, San Francisco and Washington, D.C. The New York metro alone accounts for 28 percent. Six of the seven boast a car-less household transit coverage rate of 95 percent or more, and Boston’s is 93 percent, so the metro areas with the greatest numbers of zero-vehicle households are also among those doing the best job of serving that population. Houston, Dallas and Atlanta, in contrast, all fail to serve even 75 percent of their metro car-free populations.

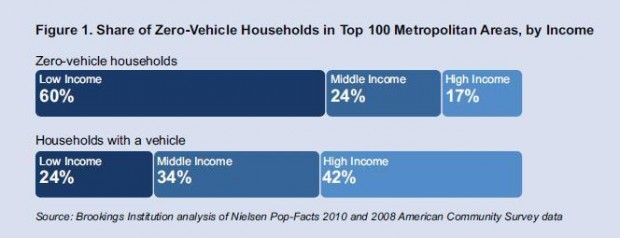

The study finds that a majority of zero-vehicle households are lower-income (see bar chart below, reproduced from the report), a good reminder that upscale city-dwellers who are car-free by choice, while they may get more attention in the media and from urban commentators, are still a minority of all car-less households. That being said, the New York metro area is one of only three of the nation’s 100 largest metros where fewer than half of all zero-vehicle households fall into the lower-income category (the other two are Lakeland, Fla., and Oxnard-Ventura, Calif.). This is probably a function of the fact that Manhattan, the core of the New York metro area, is developed at such intensity that the proposition of owning (and parking) a vehicle does not pass a cost-benefit analysis for many people, no matter their income level. New York’s far-reaching transit system and the pedestrian scale of many of its neighborhoods mean that daily activities can be accomplished more easily without a car than with one.

Some of the report’s other findings might read initially as almost comically obvious dog-bites-man stories – a majority of zero-vehicle households live in the principal cities of their metro areas, where transit is more widely available, and a majority of them use transit to get to work. But these results are useful in illustrating the circular, mutually reinforcing relationship between transportation and land-use locational decisions. As the report nicely summarizes, “This suggests that zero-vehicle households do align their settlement locations with transit provision, and that transit agencies align their routes to serve these households.” Happily, this two-way self-selection process appears to be functioning reasonably efficiently in most of the big cities with the best-developed transit systems.

Not so happily, however, in tandem with Brookings’ recent study of the transit accessibility of metropolitan employment (Missed Opportunity: Transit and Jobs in Metropolitan America; also see New Jersey Future’s commentary on the study), the high rate of co-location of zero-vehicle households with public transportation illustrates the painful irony of encouraging lower-income car-less households to live near transit while jobs are migrating away from transit on the other end.