New Jersey Future Blog

Transit-Oriented Development Is Popular, but Won’t Happen by Itself

March 15th, 2024 by Tim Evans

Westfield Northside Town Square rendering from the Lord & Taylor / Train Station Redevelopment Plan which was a 2023 Smart Growth Award recipient.

New Jersey’s transit towns are experiencing something of a revival in the last decade and a half. This is an important positive development, since transit-oriented development (TOD) advances multiple societal goals. For example, TOD is an effective strategy to reduce the state’s greenhouse gas emissions, both by encouraging transit ridership (which is much more efficient on a per-traveler basis than travel by personal vehicle), and because TOD’s compact development form brings destinations closer together, shortening vehicle trips and enabling more trips to be taken without need for a car altogether. TOD’s natural focus on pedestrian accessibility, dating to an era when most transit riders arrived at the station on foot, encourages improved pedestrian and bicyclist safety. And many (though certainly not all) transit neighborhoods feature a diverse mix of housing types—single-family detached homes, but also townhouses, duplexes, apartments above stores, small apartment buildings—that enable households of many types and income levels to take advantage of the benefits of living in a place where not every trip requires a car.

New Jersey hosts nearly 2501 transit stations, spread among 153 municipalities that host at least one of them, with many towns in the transit-rich urban core of North Jersey hosting multiple stations. The state’s transit nodes include ferry terminals; major bus terminals; stations on the PATH and PATCO rapid-transit systems, which connect New Jersey with New York and Philadelphia, respectively; and a host of New Jersey Transit commuter-rail and light-rail stations. Having invested in and constructed one of the most extensive public transit networks in the country over time, New Jersey is now blessed with plenty of opportunities to facilitate TOD.

A rendering of the South Orange Taylor Vose building and 2022 Smart Growth Award recipient. The building combines transit-oriented development, affordable housing, community usage, and local business.

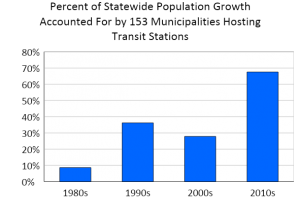

TOD is currently popular in New Jersey. The 153 transit-hosting municipalities grew twice as fast as the rest of the state between 2010 and 2020.

Facilitating more TOD would be a popular move among potential residents, if recent trends are any indication. The 153 transit-hosting municipalities grew twice as fast as the rest of the state between 2010 and 2020—the combined population of the transit municipalities increased by 7.7%, vs 3.4% growth for the balance of the state. Together, the transit municipalities accounted for more than two-thirds (67.6%) of total statewide population growth between 2010 and 2020, up substantially from the three previous decades, when jobs were clustering in suburban, car-dependent office parks, and when low-density residential subdivisions were the dominant form of new housing. Transit municipalities have transitioned from representing a disproportionately low share of total population growth in the prior three decades (they make up about half of total statewide population but were accounting for a much smaller share of new population growth) to now contributing a disproportionate majority of total growth.

Given the popularity of transit-oriented development, and its potential to attract and retain young adults who might otherwise leave the state, we should create more of it.

The resurgence of transit towns is one aspect of the recent shift in demand, particularly among young adults, toward compact, mixed-use, walkable places that offer a live-work-play-shop environment where not every trip requires a car. Transit-oriented development is by nature also pedestrian-oriented development, since transit riders become pedestrians the moment they step off the bus, train, or ferry. With transit stations historically serving as focal points for many of New Jersey’s cities and first-generation suburbs, important destinations clustered within easy walking distance of the station, capturing foot traffic among commuters en route to and from the station but also making non-work trips shorter and more efficient, often without needing a car, for all local residents, whether or not they were transit commuters. Transit towns are once again attractive to a new generation of residents who don’t want to drive everywhere, even if they are not regular transit riders.

Given the popularity of transit-oriented development (TOD), and particularly its potential to attract and retain young adults who might otherwise leave the state seeking similar but cheaper living environments elsewhere, New Jersey should be looking for ways to create more of it.

Obstacles to TOD

Many transit towns have historically embraced density, with many residential and commercial destinations all located in close proximity to the transit station and to each other, allowing many trips to be taken by transit or by non-motorized means. But others more closely resemble their car-dependent suburban neighbors in terms of the variety of housing options they offer. Among the 153 transit towns are 63 municipalities in which two-thirds of the housing stock consists of single-family detached units, compared to a statewide percentage of 53.1%; in 35 of the 153, single-family detached homes comprise 75% or more of all housing stock.

In some places, local zoning does not permit the density and diversity of housing types that TOD relies on to succeed, denying needed housing options to many households in the process. A new report from the Regional Plan Association, Homes on Track: Building Thriving Communities Around Transit, finds a whole host of commuter rail stations throughout the New York metropolitan region, including in New Jersey, that require “extensive zoning changes to allow multi-family and mixed-use at appropriate densities” in order to reach their full TOD potential. To unlock that potential, the state should consider enacting zoning reforms, as Oregon, California, Montana, and numerous individual cities around the country have done to varying degrees. Among the reform techniques are TOD overlay zones that specifically allow as-of-right creation of certain alternatives to single-family housing in transit-adjacent neighborhoods, alternatives that will both boost access to transit for a greater number and variety of households, and encourage greater return on state investments in transit by growing ridership. As a further incentive for municipalities to revisit their zoning codes to allow for greater housing variety, some of these other housing options could be used to satisfy affordable housing obligations under the Mount Laurel process, which are due to be updated and are currently the subject of legislative proposals.

Minimum parking requirements are another regulation that inhibits the development of housing near transit (and everywhere, for that matter), preventing transit-rich towns from meeting demand and undermining the general principles of TOD. Parking requirements force developers to devote land to vehicle storage that might otherwise be used for more housing units, retail options, public spaces, or other more productive uses. They reduce the affordability of the units that get built by forcing developers to spend money on parking, increasing the per-unit costs. Parking lots also force buildings farther apart, undermining the benefits of density that allow people to walk safely from one destination to another and increasing the likelihood that they will drive instead, an ironic effect in neighborhoods where transit offers an alternative to driving.

Even for towns that want to promote TOD and transit ridership, transit funding is a source of uncertainty. NJ Transit does not have a dedicated source of funding, relying instead on the vagaries of the annual budget process, and on periodic (and unpopular) fare hikes. Without stable and reliable funding, transit-hosting municipalities may be reluctant to engage in planning and development focused on state-owned facilities whose long-term viability is not guaranteed. Promoting TOD without a guarantee that the state will continue to adequately fund transit service amounts to false advertising.

The town plaza in pedestrian-friendly downtown Metuchen, a notable Transit Village. Metuchen received a Smart Growth Award in 2017 for its Woodmont Metro at Metuchen Station, a project designed to help implement its Town Center Design and Development plan.

Making TOD Happen

On the positive side, state agencies offer some valuable programs and resources for transit-hosting towns that want to encourage TOD and pedestrian-friendly street networks in the adjacent neighborhoods, including:

- The Transit Village Initiative, jointly operated by NJDOT and NJ Transit, which offers planning assistance to municipalities with transit stations that want to pursue TOD.

- NJ Transit’s Transit Friendly Planning Guide, which contains guidelines and design principles for making a place more transit-friendly, with strategies and techniques tailored to the type of development that already surrounds the transit station; recommendations address both transportation/access and land-use characteristics.

- NJDOT’s Complete Streets Design Guide, which provides a host of street design techniques for making streets more friendly to pedestrians and other non-motorized travelers, a goal that is particularly relevant in transit-focused communities

NJ Transit is also drafting a TOD policy to inform land-use decisions on and near property that it owns. New Jersey Future’s comments on the draft policy can be viewed here.

State and local governments need to address the policy and regulatory factors that stand in the way of providing TOD to present and future residents.

Our comments on NJ Transit’s TOD policy echo recommendations from our 2012 report Targeting Transit: Assessing Development Opportunities Around New Jersey’s Transit Stations. Most of the recommendations aimed at promoting more transit-friendly development are still relevant today, including:

- Expand and improve the public transit system with sustainable funding. (Recent discussions about how to fund NJ Transit demonstrate that this remains an unresolved issue.)

- Foster transit-oriented development projects on NJ Transit-owned sites. (NJ Transit’s TOD policy is an important step in this direction.)

- Strengthen state programs that foster TOD. (This could include greater support from the Transit Village program for municipalities that agree to increase zoning density near stations.)

- Facilitate structured parking. (This would mitigate the effect of surface parking lots pushing destinations farther apart and discouraging walking.)

- Enlist municipal support for zoning changes. (Given recent interest, and even some successes, in other states, state-level zoning reforms should be pursued too.)

- Foster good design to ensure attractive, pedestrian-friendly station areas. (This may entail a comprehensive review of all the disparate factors that affect how local streets get designed.)

- Promote a range of housing options near transit.

As a transit-rich state, New Jersey is not lacking in TOD potential. Recent population growth trends indicate there is demand for more such development. State and local governments need to address the policy and regulatory factors that stand in the way of providing TOD to present and future residents.

1 The exact number depends on how you count. For example, should the Glen Rock stations on the Main and Bergen commuter rail lines count as one station or two? Or the Exchange Place stations on PATH and Hudson Bergen Light Rail, and the ferry terminal of the same name? See New Jersey Future’s 2012 report Targeting Transit: Assessing Development Opportunities Around New Jersey’s Transit Stations for a thorough description of the state’s transit systems and stations.

Related Posts

Tags: Complete Streets, pedestrian accessibility, pedestrian-friendly, pedestrian-oriented developemt, pedestrians, TOD, TOD policy, Transit, transit riders, transit stations, transit towns, transit village, transit-friendly planning, Transit-Oriented, Transit-oriented Development