Warehouse Sprawl: Plan Now or Suffer the Consequences

Author: Tim Evans

Updated: December 2021

UPDATE: This report focuses mainly on the use—and in many cases, the re-use—of land for warehouse development and its impact on host communities in terms of land consumption. It does not explore in as much detail the other major negative impact of warehouses: truck traffic, and the air pollution it generates. This is a particular concern for neighborhoods in the urban core that are close to the port itself—and which are therefore especially attractive to the goods movement industry—where the air and noise pollution from trucks is just one of a myriad of environmental hazards that these communities have historically faced, based on past decisions about the siting of various noxious land uses. If port-dependent warehouse facilities are best located near the port itself from a logistical standpoint, how does one guard against further burdening adjacent neighborhoods with additional negative environmental impacts? For more on this aspect of the warehouse siting issue, click here. The recommendations section at the end of this report has also been appended to reflect these crucial considerations.

Industries devoted to the movement and storage of goods provide jobs to nearly one out of every eight employed New Jersey residents. Thanks to growth in both e-commerce and the volume of trade at the Port of New York and New Jersey, the amount of land needed for warehousing has been growing. So far, most new distribution facilities have arisen on already-developed lands in the vicinity of the port that were previously used for something else, a legacy of New Jersey’s industrial history. At least, this is true in New Jersey; the situation is different across the Delaware River in eastern Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley, where warehouse development along I-78 has been consuming farmland at an alarming rate. This warehouse sprawl could easily creep back east across the border into western New Jersey if demand keeps growing as expected. In fact, a number of municipalities in Warren County are currently considering warehouse development proposals, tempted by the boon that such development represents to local tax bases. But leaving the fate of one of New Jersey’s most important industries, and the decisions about where its need for land is accommodated, solely in the hands of our myriad local governments and their fiscal self-interest is no guarantee of a regionally-optimal solution. A regional perspective is needed, to make sure that port-oriented storage and distribution functions aren’t consuming outlying lands that are better used for farming, recreation, or some other non-industrial use, and that redevelopment opportunities near the port that are ideal for warehousing aren’t instead allocated to some other land use that lacks the same location constraints.

Goods Movement: A Key New Jersey Industry

The movement and storage of stuff is big business in New Jersey, thanks mainly to the presence of the Port of New York and New Jersey’s major facilities in Newark, Elizabeth, and Bayonne. The Port of New York and New Jersey is the second-busiest port in the country, surpassed only by the Port of Los Angeles/Long Beach. This translates to a lot of economic activity; as of 20181, nearly one of every eight employed New Jerseyans (12.2% of all employees) is employed in the wholesale trade (NAICS code 42) or transportation and warehousing (NAICS code 48) sectors of the economy, those that are devoted primarily to the storage and distribution of goods. This is the highest share among the 50 states. The comparable national percentage is only 8.6%, and only seven other states employ more than 10% of their workforce in these two sectors. These sectors together are responsible for 15.7% of New Jersey’s total payroll, also the highest in the country (and more than half again as big as the national average of 10.0%).

Growth in Port Traffic

Traffic at the port is growing—container volume has increased by 19 percent since 2016. Part of the reason for this growth is a shift in the country’s international trade profile and the logistics of ocean shipping. According to data from the Census Bureau’s Foreign Trade Statistics, our top 15 trading partners, as measured in billions of dollars of value, are China, Canada, Mexico, Japan, Germany, South Korea, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Taiwan, Vietnam, India, Ireland, the Netherlands, France, and Italy. (These top 15 countries together account for 75% of the US’s total international trade.) For the group from which shipping across the Pacific is quicker—China, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Vietnam—total trade has increased by 33.5% since 2010. But for the group from which shipping across the Atlantic is faster—the European countries plus India—total trade is up by 86.4%. The five East Asian countries on the list already accounted for 24.7% of our total international trade in 2010, up slightly to 27.9% of the total as of 2020. But the seven European countries plus India have been growing faster as a percent of the total, making up only 12.5% of our total trade in 2010 but up to 19.7% for 2020.

An increase in the share of international trade with countries that ship things to the United States via the Atlantic Ocean will tend to make East Coast ports busier; hence the Port of New York and New Jersey recently climbing to the position of second-busiest. All of that stuff coming into New Jersey from other countries has to be distributed to its final customers all over the eastern half of the country and beyond, and that means lots of warehouse space in which to store it and sort it after it is taken off the ship.

E-Commerce

Superimposed on shifting patterns of international trade is another phenomenon that is creating greater demand for warehousing all over the country: the growth in online shopping, driven especially by Amazon. Some of this could turn out to be temporary, with the COVID-19 pandemic likely producing a spike in online shopping in 2020 as retail stores closed or cut back in-store capacity, and as customers abided by stay-at-home advisories. But the slow decline of brick-and-mortar retail is an ongoing story, and e-commerce has been driving the growth of the industrial real estate market for at least the last decade. Amazon is now New Jersey’s largest employer, adding nearly 7,000 new jobs in 2020 alone and employing 40,000 people in the state.

Industrial Redevelopment

While contributing jobs to the state’s economy, the goods-movement industries do have their negative side effects, chief among them the consumption of land for warehouses (which have large building footprints) and the generation of truck traffic on the state’s roads. As of 2015,2 about 65,000 acres of land in New Jersey are devoted to “industrial” use (of which warehouses are one subcategory; the data do not identify warehousing distinctly). This represents about 4.1% of all developed land in the state and 11.8% of non-residential developed land. Interestingly, this is a slight decrease from the 66,000 acres in industrial use in 1995. Among the 34 municipalities with the greatest amounts of acres in industrial use (500 acres or more), slightly more than half (18) have seen their total industrial acreage decrease between 1995 and 2015, including Jersey City, Newark, and Elizabeth. While the total number of developed acres in the state increased by 16.9% between 1995 and 2015, the number of acres in industrial use actually decreased by 1.5% statewide.

This is likely because much of New Jersey’s new warehouse space has been constructed in redevelopment areas, on land that had previously been in use for some other purpose (often some other industrial use, like manufacturing). In the North Jersey Transportation Planning Authority’s Regional Freight Profile, a map of business square footage by industry type (see p.4 of the pdf) clearly shows the majority of large facilities in the “logistics” category in their 13-county region (covering northern and central New Jersey) concentrating in the built-out urban core of Bergen, Passaic, Hudson, Essex, Union, and Middlesex counties inside the I-287 beltway, most of it in the vicinity of the port or immediately adjacent to the New Jersey Turnpike. Lately, distribution facilities are even being proposed on land formerly occupied by dead malls or obsolete office parks, expanding the warehouse redevelopment trend into other, more recent derelict land-use types. New economic incentives for brownfield redevelopment should help sustain this trend of warehouse facilities reusing previously-developed land.

Warehouse Sprawl

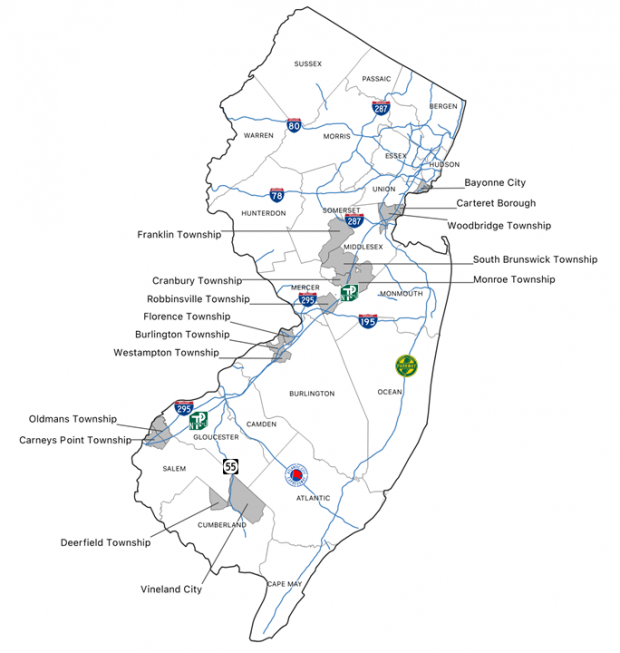

This is not to say that the consumption of land for warehousing is not an issue in certain places, or that the goods movement industry’s reuse of already-developed land can continue indefinitely. With a finite supply of redevelopable land in the urban core, warehouses have already crept southward along the New Jersey Turnpike, and along parallel I-295 south of Trenton, over the last two decades. To try to distinguish new warehouse growth from other industrial uses in the data, we looked at municipalities in which 1) industrial uses account for at least 10% of all non-residential developed acres as of 2015, 2) industrial acreage has increased by at least 20 acres from 1995 to 2015 and is greater in 2015 than in 2007 (indicating that growth in industrial land use is not confined to redevelopment areas), and 3a) employment in the two goods-movement NAICS codes (wholesale trade and transportation/warehousing) accounts for at least 12.2% of total private-sector employment (the statewide average) or 3b) has increased by at least 10% from 2003 to 20193 (indicating that the increase in industrial land use is most likely due to warehousing rather than other industrial uses). Among the 15 municipalities meeting these criteria (see map), four (South Brunswick, Monroe, and Cranbury townships in Middlesex County and Robbinsville in Mercer County) straddle the New Jersey Turnpike and US Route 130 south of I-287 but north of I-195, three (Florence, Burlington, and Westampton townships) straddle I-295 and the New Jersey Turnpike in northern Burlington County just south of I-195, and two (Oldmans and Carneys Point townships in Salem County) straddle I-295 and the Turnpike in South Jersey. Only three – Bayonne, Carteret, and Woodbridge – are located in the urban core, where new warehouse development is otherwise not generally being built on previously-undeveloped land4. If warehouse development cannot locate near major port facilities, clearly the next choice is to locate in outlying towns with direct highway access to the port (particularly via the Turnpike) and where large tracts of undeveloped land are still available.

Of the 15 municipalities in which warehousing has consumed the largest amounts of previously-undeveloped acreage since 1995 (as estimated by a combination of increased industrial land area and increased employment in the goods-movement sectors of the economy), most are clustered near New Jersey Turnpike interchanges, offering trucks a direct route to ports.

The Lehigh Valley and the Next Frontier

But land near major Turnpike interchanges, just like land near the port itself, is a finite commodity. What happens when this land starts to run out, or the host municipalities decide they’ve had enough warehouse development and put the brakes on? Other municipalities that offer both plentiful undeveloped land and easy access to highways that serve the state’s major ports—particularly I-78 and I-80—may find themselves in a similar position to the Turnpike-adjacent municipalities as the volume of goods movement in the state continues to expand, creating the need for more storage space.

Indeed, the explosive growth of warehousing in the Lehigh Valley in Pennsylvania, which New Jersey Future flagged a decade ago and which has continued unabated, is a facet of this expansion. While the tide of New Jersey residential development has receded from eastern Pennsylvania in the wake of the Great Recession of 2008, as people re-thought the wisdom of two-hour commutes to New York City and as the next generation of workers gravitated toward older, more walkable downtowns in closer-in, already-developed counties, the cheaper land in the Lehigh Valley remains as attractive as ever to industrial developers. New Jersey may have reeled in its residential sprawl for the time being, but warehouse sprawl continues to expand into eastern Pennsylvania.

Unlike in New Jersey, where redevelopment of existing industrial land has been the norm, much of the Lehigh Valley’s new warehousing has gone up on former farm fields. The Lehigh Valley lost about 25% of its farmland between 1997 and 2017, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. And more is on the way: A 2015 study commissioned by the Lehigh Valley Planning Commission found that the volume of freight moving through Lehigh and Northampton counties was projected to double by 2040. Most of this is likely to move by truck, as is presently the case with 90 percent of the Lehigh Valley’s freight tonnage.

As storage and distribution facilities creep farther and farther west into Pennsylvania along I-78, industrial developers may start taking a second look at lands that are near, but not necessarily immediately adjacent to, the interchanges off I-78 and I-80 in Hunterdon and Warren counties. Just as warehouses have begun oozing outward away from I-78 interchanges in Lehigh and Northampton counties along the four- and sometimes two-lane surface roads that feed into the interchanges, warehouse developers may decide that undeveloped lands in western New Jersey that are similarly situated are now worth the price premium in exchange for shorter distance to the port. According to the New Jersey Highlands Coalition, several municipalities in Warren County are currently proceeding with plans to allow new warehouse developments. One of these, Franklin Township, recently went as far as to attempt to designate a plot of productive farmland as an area in need of redevelopment (the effort was rejected by the Department of Community Affairs, which reviews these designations) in order to trigger special powers that would enable the township to transfer the land to a warehouse developer. Higher land values, which act as a deterrent to a business characterized by large building footprints, have thus far shielded the farm fields of western New Jersey from the scenario currently unfolding in the Lehigh Valley, but there is no guarantee that the financial calculus won’t change as more of the prime spots in eastern Pennsylvania get developed.

Chasing “Ratables”

Complicating matters is that warehouse development can look like a winner from a fiscal perspective, making it attractive to local leaders. As the example of Franklin Township in Warren County illustrates, municipal officials are often tempted to court industrial properties like warehouses because they are “clean ratables”—they help keep property taxes low by generating property tax revenue without demanding much in the way of government services. In particular, they don’t bring in school children, who are expensive to educate. Local leaders’ fiscal incentives can thus be at odds with the desires of average citizens, who may not want more trucks on their roads or more warehouse buildings eating up hundreds of acres of farmland.

Regional Importance, Regional Perspective

Port-related goods movement and storage is an unusual land use in that, unlike residential, retail, or office uses, it cannot simply be located anywhere. Ideally, facilities for storing and sorting goods arriving in the state by ship should be located as close to the port as possible, to reduce the need to truck all this stuff to its first land-side destination and to allow for some shipments to be placed directly onto rails at the port. Mis-siting a large storage or distribution facility can have lasting consequences in terms of creating truck traffic where there didn’t need to be any. The warehousing corridor stretching south into Middlesex, Mercer, and now northern Burlington counties along the Turnpike demonstrates this effect, having generated sufficient truck traffic to prompt the widening of the Turnpike from Exit 9 down as far south as Exit 6. But at least this truck traffic is confined to the state’s major highway artery. If warehousing starts creeping farther away from the port and farther away from the Turnpike, it can put trucks onto more local roads—and into local neighborhoods—that are not equipped to handle them.

Because of the importance of the warehousing industry to the economy of New Jersey, and to the logistics of distributing goods all over the northeastern United States, its unique land-use needs should perhaps not be left in the hands of the state’s myriad of local governments. Each of New Jersey’s 565 municipalities has its own parochial needs and interests, which may not add up to the most efficient macro-level solution from a goods-movement standpoint. Involving higher levels of government, and perhaps also port officials and representatives from the warehousing industry, in decisions about where to site large storage and distribution facilities could help avoid situations in which a site ideally suited to one specialized land-use type instead gets developed as something else.

For example, in 1999 the Mills at Jersey Gardens outlet mall was built on the site of a former landfill in Elizabeth. The mall provided a much-needed infusion of commercial property into the tax base of the struggling city and as such represented a rational and positive decision on the part of local leaders in Elizabeth. However, the land is located between the Maher container terminal and a Norfolk Southern intermodal rail yard and might have been better used (from a more macro perspective) as expansion space for Norfolk Southern’s port-adjacent operations, enabling some freight to be diverted directly onto the rail system and keeping hundreds of trucks off the road. Denied the opportunity for port-adjacent expansion by a mall that didn’t need to be near the port, Norfolk Southern instead opened a new intermodal yard on part of the old Bethlehem Steel plant property in Bethlehem, PA, which offered a large tract of redevelopable land but which requires goods from the port to be trucked across New Jersey on I-78 before they can be transloaded onto the rail network.

Conversely, it is also not ideal if the property-tax benefits of warehouse development induce local government officials to shut out other land uses that might be even better suited to a particular parcel of land. The conversion of prime farmland—whether in western New Jersey or in the Lehigh Valley—to industrial use is one example of warehousing displacing another regionally beneficial and location-specific land use. Taken individually, these decisions appear inconsequential, but cumulatively they can add up to a severe blow to either state’s agricultural production if left unchecked.

Missed opportunities can arise in redevelopment situations too. Consider the 66-acre former Congoleum site immediately adjacent to the Hamilton commuter rail station, along NJTransit’s busy Northeast Corridor—and just off the Sloan Ave. interchange of I-295. The site presents Hamilton Township with a rare opportunity to create new mixed-use, transit-oriented development (TOD) and offer potentially hundreds of new residents the option of reducing their dependence on driving, an outcome with region-wide benefits in terms of traffic, air quality, and greenhouse gas emissions. But a commercial developer has proposed a warehouse for the site. Large redevelopment parcels immediately adjacent to a highway interchange (a desirable trait for warehousing) are not easy to come by, but neither are large redevelopment parcels immediately adjacent to a busy commuter rail station (a necessary component of TOD). When a parcel of land could potentially be used for either of two regionally important land-use types, leaving the decision solely up to local government may not lead to a regionally optimal outcome.

Recommendations

Aside from taking a regional perspective on where to locate facilities associated with the storage and distribution of goods arriving at the port, there are several other steps that state and local governments and the warehousing industry itself can consider, to prevent warehouse sprawl from becoming a widespread problem. These principles roughly mimic the strategies New Jersey has used to rein in residential sprawl over the last two decades.

- Assign to the State Planning Commission (SPC) and its staff at the Office of Planning Advocacy the task of developing a statewide warehousing plan. The plan would establish criteria for identifying sites that are most suitable for warehouse development, taking into consideration existing land uses, proximity to the port, proximity to major highways and freight rail lines, local road network design and capacity, environmental and open-space concerns, social justice concerns, infrastructure capacity, and the future impacts of climate change. To prevent further deleterious effects on environmental justice communities, where residents have historically been disproportionately exposed to a variety of environmental stressors, the plan should recommend against siting new warehouse developments in such communities if they are projected to worsen air quality there. The plan could use criteria parallel to those outlined in New Jersey’s recently passed environmental justice law, S232, which establishes the Department of Environmental Protection’s authority to regulate certain classes of point-source facilities in these same neighborhoods.

- Encourage warehousing to continue using redevelopment sites: Most of New Jersey’s population growth since the Great Recession has been taking place in already-developed areas, taking pressure off the state’s remaining open land for residential development. Thus far, warehouse development has been able to follow a similar pattern, at least in New Jersey if not in the Lehigh Valley. State and local governments should encourage and facilitate this trend in the future. This is important not just for larger facilities that want to locate as close to the port as possible but also for smaller distribution centers like the “delivery stations” that Amazon has been opening throughout the state. The goal for these smaller facilities is to be close to the customer base, with the “last mile” leg of the delivery in mind, rather than close to the port. Because they are focused on serving a much smaller geographic area, they could potentially make a good fit for land formerly occupied by defunct office buildings or by the dead malls and other brick-and-mortar retail centers that have become casualties of the increase in online shopping. These more suburban redevelopment sites show up everywhere (like a former rehabilitation center in Kearny that is being repurposed as a distribution center), not just in port-adjacent locations, so their reuse could allow the warehouse redevelopment trend to continue even as the warehousing industry decentralizes with the growth in e-commerce.

- Build up rather than out: Just as building multi-story apartment buildings consumes far less land per capita than single-family homes on large lots, warehouses might be able to shrink their building footprints by going more vertical. Emerging technology may help further this goal, in the form of “High Cube” warehouses, which stack goods vertically and use automated retrieval systems to remove packages from high shelves. Of course, taller warehouses might meet with some of the same aesthetic, congestion, and quality-of-life objections from neighbors as taller condo buildings do, but the argument that density saves land would work equally well to counteract these objections as it does for residential development.

- Enable more goods to be shipped by rail: Just as rail transit produces congestion and air-quality benefits by moving large numbers of people in far less space and with far lower carbon emissions per capita than if the same number of people all drove their own personal vehicles, so too can a freight train take hundreds of trucks off the road. And trains are three to four times more efficient than trucks on a per-ton-mile basis, meaning a train can move a given volume of stuff with 75% less greenhouse-gas emissions than if the same stuff were shipped by truck. The vast majority of freight currently moves by truck, both in New Jersey and nationally, partly because roads are publicly funded and extend basically everywhere, whereas railroad networks were built and are operated by private entities and are not nearly as spatially extensive. Increasing rail’s share of goods movement may involve getting shippers to view rail-adjacent sites with the same enthusiasm as sites near highway interchanges (The Home Depot, which in many ways behaves like a wholesaler, is currently pursuing a rail-focused strategy), and incentivizing railroads to consider competing with trucks for shorter hauls.

- Elevate medium- and heavy-duty vehicles to the top of the priority list for vehicle electrification and deploy them first in overburdened communities. To reduce the carbon and air-pollution footprints of the large fraction of freight that continues to move by truck, particularly in environmental justice communities in the older urban core of the state, New Jersey should continue to pursue its own version of California’s Advanced Clean Trucks rule and should also continue its existing incentive programs to encourage and assist businesses and institutions in acquiring zero-emissions trucks.

- Prioritize the electrification of the port itself, including on-site equipment and yard tractors, in addition to the over-the-road trucks that pick up or deposit freight there. The recent introduction of the first batch of electric yard goats is a first step in this direction.

1 2018 County Business Patterns data at https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cbp/data/tables.2018.html

2 Based on 2015 land use/land cover data (the most recent available) from the NJ Dept. of Environmental Protection, at https://gisdata-njdep.opendata.arcgis.com/datasets/6f76b90deda34cc98aec255e2defdb45

3 2003 is the earliest year for which employment data by 2-digit NAICS code are available at the municipal level.

4 The remaining three municipalities in this group of 15 – Franklin Township in Somerset County and Deerfield Township and Vineland in Cumberland County – do not fit any obvious pattern, other than being located near more outlying highway interchanges.