New Jersey Future Blog

Many States Making New Investments in Water Infrastructure

June 28th, 2017 by New Jersey Future staff

New Report Assesses Landscape of Programs

The following article and related report were both written by Jersey Water Works intern Vivian Chang

Water infrastructure across the United States is crumbling. The water crisis in Flint, Michigan, is just one example of the major problems facing communities. The American Water Works Association estimates that, over the next 25 years, there will be a $1 trillion deficit for meeting service demands in drinking water systems alone. Such funding gaps are having severe negative effects on water quality and social and economic outcomes. Water infrastructure across the United States is crumbling. The water crisis in Flint, Michigan, is just one example of the major problems facing communities. The American Water Works Association estimates that, over the next 25 years, there will be a $1 trillion deficit for meeting service demands in drinking water systems alone. Such funding gaps are having severe negative effects on water quality and social and economic outcomes.

Water infrastructure across the United States is crumbling. The water crisis in Flint, Michigan, is just one example of the major problems facing communities. The American Water Works Association estimates that, over the next 25 years, there will be a $1 trillion deficit for meeting service demands in drinking water systems alone. Such funding gaps are having severe negative effects on water quality and social and economic outcomes. Water infrastructure across the United States is crumbling. The water crisis in Flint, Michigan, is just one example of the major problems facing communities. The American Water Works Association estimates that, over the next 25 years, there will be a $1 trillion deficit for meeting service demands in drinking water systems alone. Such funding gaps are having severe negative effects on water quality and social and economic outcomes.

Local and regional water utilities play the lead role in water infrastructure funding by leveraging user rates. In addition, state and local governments typically rely on financing mechanisms like the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s State Revolving Fund programs and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Rural Development funds. Meanwhile, some states have created programs that raise new revenue for direct funding to fix systemic gaps in infrastructure. In light of these efforts, Jersey Water Works is releasing a new report, Upgrading Our Systems: A National Overview of State-Level Funding for Water Initiatives, which assesses the landscape of such initiatives on sustainable water infrastructure.

Upgrading Our Systems includes original research on current, past, and proposed state programs that raise new revenue for drinking water, wastewater and stormwater infrastructure. Programs are included if they meet three requirements: They bring in new revenue; they are partly or entirely independent from state revolving funds (SRFs); and they commenced between 2001 and April 2017. The report is comprehensive in identifying all voter-approved state water funding programs, but it may omit state programs that were legislatively approved and did not appear on the ballot. More additional research is needed to identify all state-level water fund programs.

Twenty-eight current programs from 14 states were identified, along with three repealed or unsuccessful initiatives, and three proposals for funding programs as of April 2017. The report includes a representative sample of legislatively-authorized programs, but is not inclusive of every state program. Among the report’s findings:

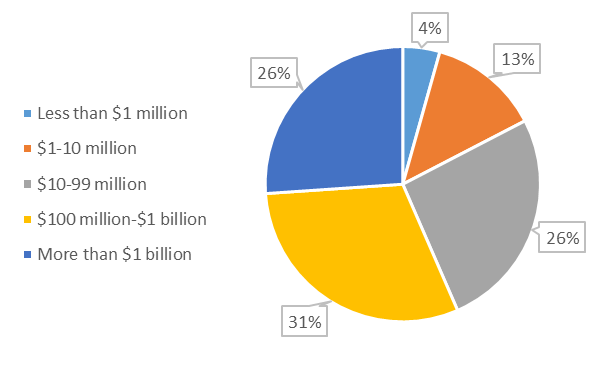

1. The mean amount raised by each state program was $1.1 billion, and the median amount was $200 million.

Figure 1. Amount of Revenue Raised by Each Program

Some of the figures above represent state programs funded on an annual basis, while others are for multi-year programs, Some of the figures above represent state programs funded on an annual basis, while others are for multi-year programs,

2. Most programs are funded by bonds or through the state budget, and disburse through grants or a combination of grants and loans.

Figure 2. Sources of Program Revenue

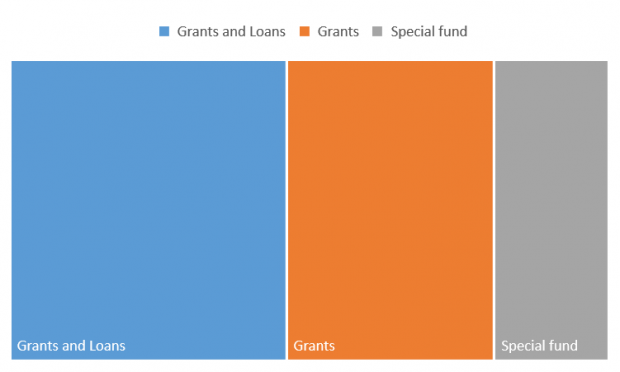

Figure 3. Fund Disbursement Structure

More than half of the programs reviewed raise revenue through bonds (general obligation bonds or special revenue bonds), which typically have payback periods of 10 to 40 years. Six programs are funded through a state budget item or the general fund. Five programs create a new tax or fee to fund water infrastructure. More than half of the programs reviewed raise revenue through bonds (general obligation bonds or special revenue bonds), which typically have payback periods of 10 to 40 years. Six programs are funded through a state budget item or the general fund. Five programs create a new tax or fee to fund water infrastructure.

Nearly half of all reviewed programs distribute the funds through a combination of grants and loans, while slightly fewer distribute the funds as grants only. Many of the grant programs are structured as matching grants to encourage greater local investment. Five programs establish a special fund and administrative board to oversee disbursement of funds.

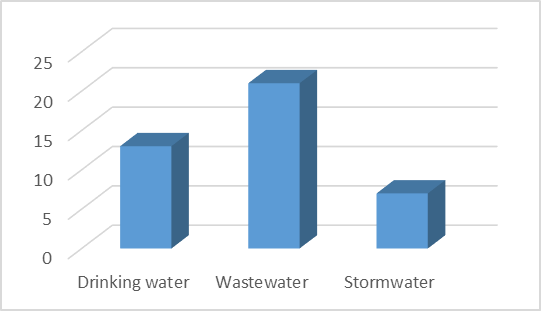

3. All three major types of water infrastructure are covered; funding for wastewater systems is the most common.

Figure 4. Types of Water Infrastructure Covered

Of the 28 currently operating programs reviewed, 19 programs provide funding for wastewater systems, 11 fund drinking water systems, and eight fund stormwater systems. Many of the programs highlighted cover two or more forms of water infrastructure.

Upgrading Our Systems also includes four case studies of major state-level water programs. These case studies demonstrate a variety of options in program structure, revenue sources, funding goals, and types of projects funded. Lessons learned from these states can give options to other states looking to design new programs.

The final section of the report provides a literature review of state government reports examining the current status of water infrastructure. Each of these reports assesses the state of physical infrastructure and any funding gaps in water financing. Recommendations proposed by these states include further assessment, long-term planning, increasing efficiencies and sustainability, and finding new sources of funding.

Clean water is imperative to achieving the social and economic outcomes that are within our grasp. Some states are acting intentionally to leverage new revenues to create sustainable water infrastructure. By continuing the effort to improve our drinking water, wastewater, and stormwater systems, state governments can prevent the negative impacts of crumbling infrastructure for communities across the country.

Download Upgrading Our Systems: A National Overview of State-Level Funding for Water Initiatives