New Jersey Future Blog

Highlands Development Regulations Not Responsible for Exurban Slowdown

April 24th, 2014 by Tim Evans

The planned Brookwood Green at Byram Village Center. Byram’s Village Center plan will add 134 residential units in its planning area, which comprises only 1.6 percent of its total land area.

Is the recent slowdown – and in some cases, outright reversal – of population growth in New Jersey’s northwestern exurbs primarily attributable to restrictions on development imposed by the Highlands Water Protection and Planning Act of 2004, as sometimes claimed by business and real estate interests and political figures? Or is there a larger phenomenon at work?

As our recent analysis showed, the population growth dynamic in New Jersey (and indeed nationally) since the recession in 2008 has been one of new growth happening in urban areas and older suburbs – places that hit their peak populations many decades ago but are now experiencing a second wind. Meanwhile, the outer-suburban counties that topped population growth lists in the 1990s and the early part of the 2000s fell to the middle of the pack, or even to the bottom.

Hunterdon, Warren, and Sussex counties are an example of this last case. From 2000 to 2008, Hunterdon and Warren were both among the top 10 fastest-growing counties in the state, and Sussex was number 11. And in the 1990s, Hunterdon ranked third and Warren ranked fifth. But things have changed, and all three counties had fewer residents in 2013 than in 2008.

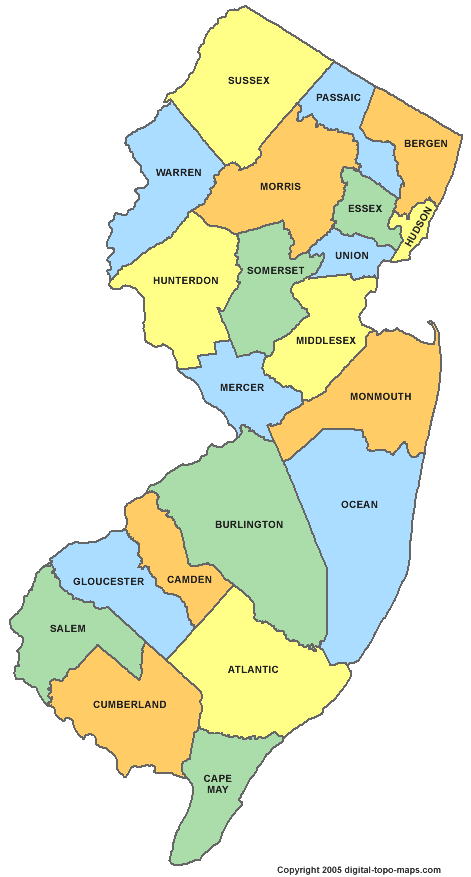

Is it because restrictions on development in the Highlands have put the brakes on growth? Large portions of the three counties’ land areas lie within the Highlands region, as defined in the legislation – 38 percent of Sussex County’s territory, 46 percent of Hunterdon’s, and a full 74 percent of Warren’s. However, in many parts of the Highlands – the part known as the “planning area” – land-use decisions and development approvals are still under the exclusive control of municipal governing bodies. It is only in the “preservation area” where local land-use regulations are required to conform to the New Jersey Highlands Council’s requirements. The preservation area accounts for a smaller percentage of these three counties’ total land area – 21 percent of Sussex, 23 percent of Hunterdon, and 29 percent of Warren.

Still, these three counties’ preservation-area acreages amount to more than 200,000 acres. Could restrictions on development across an area this large be putting downward pressure on growth? Fortunately, we don’t need to wonder about this – we can look at data at the municipal level, to see what is going on within each of these counties.

If it were really true that Highlands regulations were responsible for smothering growth in New Jersey’s exurban northwestern corner, and that in the absence of these regulations these counties would be continuing to grow rapidly, one would expect to see continued growth in the parts of these counties that are not in the Highlands region. But this is not the case: The 28 municipalities in these three counties that are outside the Highlands region collectively declined in population by 1.2 percent from 2008 to 2012. (Municipal population estimates for 2013 will not be released until later this year; 2012 is the most recent year of population estimates available at the municipal level.) In contrast, the 88 Highlands municipalities (some of which are in other counties but are nonetheless governed by the same legislation) together experienced a small – 0.7 percent – increase in population over the same time period. This increase is smaller than the statewide increase of 1.8 percent, but is an increase all the same.

This is the mirror image of what happened from 2000 to 2008, when the 88 Highlands municipalities outpaced the statewide growth rate – a 4.2 percent increase in the Highlands vs. 3.5 percent growth statewide – but were in turn outpaced by the non-Highlands municipalities in Hunterdon, Warren, and Sussex, which collectively grew by 6.0 percent over the same period. Thus the exurban reversal was actually more pronounced outside the Highlands region than within it.

If one needs further evidence that the exurban slowdown is a product of forces that transcend the Highlands, one need look no further than the other side of the Delaware River, at Monroe and Pike counties in northeastern Pennsylvania. These counties were two of the top three fastest-growing counties in the entire northeastern United States in the 1990s and again in the first part of the 2000s, and they have both now declined in population from 2008 to 2013. These two counties are unaffected by the Highlands Act or any other piece of New Jersey legislation.

A closer look within the Highlands also reveals the same pattern as is taking shape statewide – older, built-out places on the rebound, with low-density suburban development tapering off. The 52 municipalities that lie at least partially within the Highlands preservation area, which tend to be the less-developed areas, together grew by 0.5 percent in population between 2008 and 2012. On the other hand, the 36 municipalities lying entirely in the Highlands planning area grew by a more robust 1.1 percent, closer to the statewide rate. These planning-area municipalities have a median build-out percentage of 85.4 percent. They are the places to which the Highlands Master Plan calls for steering new growth – older centers like Netcong, Morristown, Dover, and Lebanon Borough, along with maturing suburban townships like Parsippany and Bernards along the more developed eastern edge of the Highlands region. (The pattern is not uniform, however – some older Highlands centers, such as Hamburg, Phillipsburg, and Washington Borough, lost population from 2008 to 2012.) In its effort to promote growth in existing centers, the Highlands Master Plan would appear to be abetted by the same larger demographic and economic forces that are producing the same phenomenon at the statewide level.

Interestingly, these results are consistent with what has happened in the Pinelands, another region of New Jersey whose land-development decisions are overseen by a regional council and where the creation of that regional governing body was initially criticized as precipitating an end to future growth. In fact, our recent analysis of population growth in and around the Pinelands found that the Pinelands Comprehensive Management Plan has largely succeeded at steering growth into centers within the Pinelands, while not suppressing the overall growth of the region.

Great article. I would suggest that you communicate your findings to the Highlands Council by a brief presentation.

We would like to link to your article from our website.

The Council is trying to let a contract for a fiscal analysis as required for RMP update and seems to be bamboozled by ideology and is largely without facts.

your article would help a great deal in moving this process toward a rational analysis.

Please contact me at 973-539-7547 or dpeifer anjec

anjec org

org

What is the source for the 2008 to 2013 Pike and Monroe County population assumptions?

2008 and 2013 county population estimates for the Pennsylvania counties are from the same source as for NJ — the Census Bureau’s intercensal population estimates.

The link for 2010 thru 2013 is here: http://www.census.gov/popest/data/counties/totals/2013/CO-EST2013-01.html

You just need to click on the state you want.

Annual estimates for 2000 thru 2009 are here: http://www.census.gov/popest/data/intercensal/county/CO-EST00INT-01.html