New Jersey Future Blog

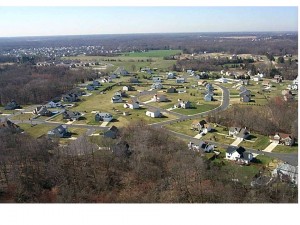

Sprawl Isn’t Dead, It’s Just Hibernating

February 10th, 2014 by Tim Evans

The End of Sprawl?

Did the 2008 recession really rewrite the development playbook? Are demographics really destiny (pdf)? Commentators of many stripes have recently been declaring that the age of suburbanization is at an end, and that the future of land development is going to look a lot like the past, with people returning in droves to in-town living. Now, some of their prognostications are actually starting to show up in data. Our two-part series takes a look at some of the sorts of data patterns that one would expect to see if we really were standing at the threshold of a new era of redevelopment. Part II of a two-part series. Read Part I here.

In part 1 of this series, we looked at population growth at both the county and municipal level from 2008 to 2012 and noted that it was happening in a very different group of places from what had been the case between 2000 and 2008 (and in earlier decades). Older, already-developed towns and counties were much more likely to be growing over the past four years than they had for many years, or even decades, prior. Meanwhile, the fast-growing suburban counties of the 1990s and early 2000s were no longer dominating the growth list, and in fact some of them have even reversed course and lost population since 2008.

Does this mean sprawl has ground to a halt? What about the counties that were among the top 10 fastest-growing between 2000 and 2008 but continued growing from 2008 to 2012, even if their growth rates have slowed somewhat? This group includes Gloucester, Ocean, Atlantic, Somerset, Cumberland, Morris, and Burlington counties, as well as Middlesex, which has some things in common (namely its northern half, north of the Raritan River) with the urban-core counties topping the 2008-2012 list and some things in common (its southern half) with the outer-suburban counties. In this article we take a look at what is going on within these counties, to see if the growth that is still happening there is happening in the same low-density places as before the 2008 recession or if it is now happening in the counties’ older centers.

Two distinct pictures emerge, depending on which half of the state we examine. In the south, things look mostly like business as usual, only slower. Annual growth rates from 2008 to 2012 were slower just about everywhere than they were from 2000 to 2008, but the fastest-growing municipalities in the later period are still mostly the same spread-out, use-segregated, car-dependent suburban townships that dominated the growth list from 2000 to 2008 – places like Barnegat, Ocean, Jackson, Little Egg Harbor, Eagleswood, and Stafford townships in Ocean County; Woolwich, East Greenwich, Harrison, and South Harrison townships in Gloucester County; and Egg Harbor, Hamilton, and Galloway townships in Atlantic County. (See Table 1 for a list of the top five fastest-growing municipalities in each county for 2000-2008 and for 2008-2012.) However, most of these saw their annual growth rate drop by more than half. And some formerly-growing suburban townships actually experienced population losses from 2008 to 2012 – particularly West Deptford, Franklin, Mantua, Greenwich, Logan, and Washington townships in Gloucester County. At the same time, many of the small centers in these outer-suburban South Jersey counties also lost population – places like Woodbury, Westville, Pitman, Paulsboro, Atlantic City, and most of Ocean and Atlantic counties’ shore towns. The only growth spots that might be taken as a sign of a trend toward redevelopment are a handful of relatively compact towns that grew faster, or nearly as fast, from 2008 to 2012 than they did in the early 2000s: Lakewood, Pleasantville, and Swedesboro. But these are not enough to constitute a trend.

In the north, aside from the urban-core counties of Hudson, Bergen, Passaic, Essex, and Union all rebounding, there is some evidence for redevelopment in maturing-suburban Morris County as well. The county’s fastest-growing municipalities from 2008 to 2012 were a trio of what might be called lower-density centers – Riverdale, Chester Borough and Mount Arlington, places that are mostly built-out and with relatively well-connected street networks, albeit built at fairly low densities. Despite their lower densities, most new growth in these places is likely to be redevelopment or infill. At the same time, growth in the formerly fastest-growing exurban townships of Mount Olive and Harding has slowed to about half its annual rates earlier in the decade, though both townships are still growing.

The faster-growing counties in the middle part of the state – Middlesex, Somerset, and Burlington (the northern end of which is more suburban Trenton/Princeton than suburban Philadelphia) – are, fittingly, a mixed bag. In Burlington, the fastest-growing townships of 2000-08 were mostly in the northern half of the county and have all cooled off considerably – Mansfield, Hainesport, Bordentown Township, Chesterfield, Westampton and Lumberton. This curtailing of exurban growth is similar to what has happened in northern and central New Jersey. However, Delanco and Cinnaminson (closer to Philadelphia) are the only mature suburbs in the county that have moved toward the top of the growth list. Most of the county’s other boroughs and older townships grew very slowly or lost population, although so did some low-density townships. No clear pattern emerges in Burlington.

In Somerset and Middlesex counties, the move toward redevelopment is a little more visible. Many smaller boroughs in the two counties that were losing population from 2000 to 2008 transitioned to population gains for 2008-2012: Somerville, Manville, Highland Park, Middlesex, Milltown, and Jamesburg. Many other nearly-built-out places are growing faster now than earlier, including some older, more densely-developed townships – Carteret, Piscataway, Sayreville, Dunellen, Perth Amboy, Spotswood, Edison, and Woodbridge in Middlesex County and Bound Brook, Green Brook, and Bridgewater in Somerset. Even in the more suburban townships among this group, most new development is likely to be redevelopment, due to the diminishing supply of developable land. In Somerset, the older boroughs of Raritan and South Bound Brook were actually the two fastest-growing municipalities in the county for 2008-2012. But not all new development in the two counties is redevelopment. The lower-density townships in the southern parts of the counties – Monroe, South Brunswick, Cranbury, and Plainsboro in Middlesex, and Hillsborough and Montgomery in Somerset – continue to grow quickly, though Hillsborough is the only one of these in which the annual growth rate was greater for 2008-2012 than for 2000-2008.

The trend toward redevelopment manifests in almost all of the eight counties named earlier (Cumberland being the only exception) when each county’s municipalities are sorted by the ratio of 2008-2012 growth to 2000-2008 growth. (See Table 2.) In almost every case, the municipalities whose growth rates increased after 2008, or decreased less than elsewhere in the county, or which moved from having lost population between 2000 and 2008 to gaining between 2008 and 2012, are the county’s older centers, places like Atlantic City, Bordentown, Woodbury, Highland Park, Carteret, Morristown, Boonton, Point Pleasant, and Somerville.

Overall, there are promising signs that sprawl really has been curbed throughout much of North Jersey, and that redevelopment is on the rise, with plenty of cities, towns, boroughs, and older, built-out suburban townships seeing more vigorous population growth since 2008 than they had seen in previous years or, in some cases, decades. Farther to the south, however, the picture is less clear. Camden County – South Jersey’s smaller version of the North Jersey “urban core” of Bergen, Passaic, Hudson, Essex, and Union – actually lost population between 2008 and 2012 (and not just because of the city of Camden), and the older towns and boroughs in the other counties have not moved toward the top of the growth rate list the same way that similar places have done in the northern counties. It is certainly true that many of the fastest-growing suburban townships in South Jersey have seen their earlier growth rates drop off significantly, but redevelopment has not stepped in to fill the gap; rather, exurban growth simply seems to have gone into hibernation with the downturn in the economy. This raises the possibility that development patterns in South Jersey may revert to business as usual – low-density development on the fringe – when the economy picks up again.