New Jersey Future Blog

Ensuring Equity in Transit-Oriented Development

June 25th, 2021 by Tim Evans

State leaders are embracing the concept of transit-oriented development (TOD), which encourages residential and commercial development to locate within walking distance of public transit stations, enabling residents to complete some or all of their trips without a car. The private sector also recognizes the demand for housing in transit-accessible towns. But with transit-adjacent neighborhoods being a limited commodity, how do we make sure the option of living near transit is available to everyone?

The Ensuring Equity in Transit-Oriented Development session examined population patterns with respect to race and income around New Jersey’s transit stations. This session was built around a report, Ensuring Equity in TOD: A Blueprint for State-Level Reform in New Jersey, prepared by a policy workshop class at Princeton University under David Kinsey, Visiting Lecturer in Public and International Affairs, and with New Jersey Future and the Fair Share Housing Center as clients. Kinsey moderated this 2021 New Jersey Planning and Redevelopment Conference session, and the speakers included Wendy Gomez and Alex Merchant, two of the students from the class; Nat Bottigheimer, New Jersey Director at the Regional Plan Association; Eric Dobson, Deputy Director of the Fair Share Housing Center; and Tim Evans, Director of Research at New Jersey Future.

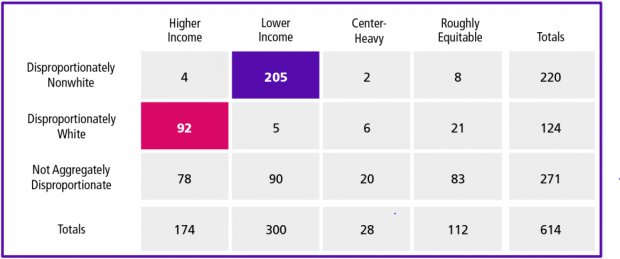

Striking differences in racial and economic equity and opportunity characterize the neighborhoods surrounding New Jersey’s 244 transit stations. Among 614 census tracts that are within a half-mile of one or more transit stations, 205–a full one-third–are both disproportionately nonwhite and disproportionately low-income. Meanwhile, another 92 tracts are both disproportionately white and disproportionately upper-income. Only 83 tracts roughly resembled statewide population distributions with respect to both race and income. In other words, New Jersey’s transit stations, as a whole, display an alarming degree of segregation by race and income, indicating significant room for improvement in terms of equity.

The Princeton students discussed several policy changes suggested by the class that might enable state agencies to address questions of equitable access to transit. They recommend that the Housing and Mortgage Finance Agency make changes to its criteria (known as the Qualified Allocation Plan, or QAP) for awarding credits in the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program in ways that would steer new lower-income housing into transit station areas in which lower-income households are underrepresented, while avoiding station areas where such households are already concentrated.

The class recommends that New Jersey Transit’s recently-created Real Estate, Economic Development and Transit Oriented Development office establish an affordable housing policy for joint development projects to ensure that affordable housing is part of any new development that happens on station-area land owned by NJ Transit. Dobson pointed out that, by not having such a policy, NJ Transit is currently in violation of the Fair Housing Act, which requires any development on state-owned property to have an inclusionary housing component.

The class recommends that the New Jersey Department of Transportation’s Transit Village program require affordable housing planning for a municipality to qualify as a Transit Village. Evans mentioned that the program is currently opt-in, but that New Jersey Future would like to see NJDOT promote the program more proactively. Furthermore, Evans agreed that creating opportunities for affordable housing in station areas should be part of the criteria.

The students indicated that the station-area tracts in which racial and income profiles most closely resembled those of the state also tended to have the most diverse arrays of housing options, enabling households across the income spectrum to afford to live near transit. (Because of the strong correlation between race and income, greater income diversity also usually results in greater racial diversity.) The panelists agreed that this points to housing diversity as an important contributor to more equitable outcomes in station areas and that zoning reform is needed in order to foster a wider variety of housing types. The class suggests that the legislature create an “unmet need TOD zoning overlay” that would allow developers to build mixed-income housing with an affordable set-aside in transit-adjacent tracts in any municipality having an outstanding Mount Laurel affordable-housing obligation.

The panelists agreed that New Jersey should follow the lead of cities like Chicago, Los Angeles, and Minneapolis, as well as states like Massachusetts and Oregon. These cities and states have recently enacted some form of zoning reform designed to increase the variety of housing in certain places, whether it be prohibiting single-family-only zoning, creating as-of-right upzoning in transit station areas, or allowing developers of affordable housing to override local zoning. Gomez mentioned that Los Angeles incorporated an equitable TOD policy in 2016 that has nearly doubled the supply of affordable housing near transit.

Given the importance of TOD in attracting younger people who want to live in compact, walkable neighborhoods, as well as the role of increasing transit ridership in helping the state meet its greenhouse gas reduction goals, state leadership is critical in ensuring that the benefits of living near transit are made available to everyone, regardless of race or income.

Related Posts

Tags: equity, NJPRc, NJPRC21, Planning and Redevelopment Conference, Transit-Oriented