New Jersey Future Blog

Redevelopment Is the New Normal

June 12th, 2020 by Tim Evans

Since the end of the decade of the 2000s, New Jersey Future has been documenting the return of population growth to the state’s cities, towns, and older, walkable suburbs, noting that redevelopment (new development happening in places that are already built-out) has become the “new normal.” While it makes intuitive sense that increased growth in already-developed places has likely alleviated development pressure on the exurban fringe, we have previously lacked the ability to quantify this effect.

Recently-released 2015 land use/land cover data from the Department of Environmental Protection offer an opportunity to assess the state of land development in New Jersey.

- From 1986 to 2007, New Jersey’s rate of land development was nearly double the rate of population growth; from 2007 to 2015, the ratio dropped to more like 1:1

- Since 2007, most of the state’s population growth has been happening via redevelopment, in places with little to no buildable land left

- Redevelopment can take many forms, from infill projects on surface parking lots, to adaptive reuse of existing buildings, to building whole new neighborhoods on large derelict properties

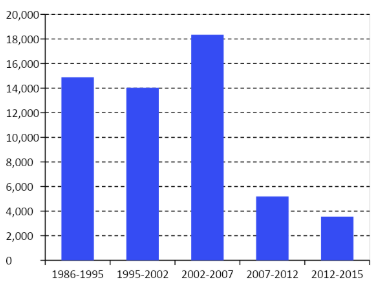

Now, with recent new data from the Department of Environmental Protection’s Land Use/Land Cover mapping project, and a value-added analysis by researchers at Rowan and Rutgers universities, we can clearly see the degree to which redevelopment has been saving land. From 1986 (the earliest year for which the project has produced data) through 2007,1 the number of acres annually converted to urbanized uses held steady in a range roughly between 14,000 and 18,000 acres (see Figure 1). But post-2007, that figure has dropped dramatically, first to a little more than 5,000 acres per year between 2007 and 2012, and then even further, to about 3,500 acres per year, between 2012 and 2015.

Figure 1. Newly-Developed Acres Per Year

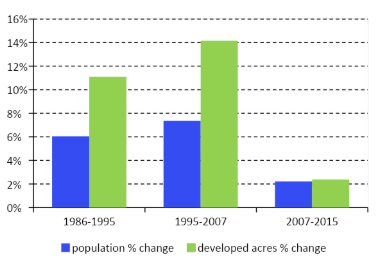

It is true that population growth has dropped off over the last decade as well, reducing the pressure to develop new land, but this alone does not come close to explaining the drop in the rate of land development. Between 1986 and 1995, and again between 1995 and 2007, New Jersey’s rate of increase in developed acres was nearly double the rate of population growth (see Figure 2). But between 2007 and 2015, the rates were nearly identical; population growth slowed, but new land development slowed by a lot more. In the latter period, the state thus developed far fewer new acres for every new resident than had been true in prior decades. How did this happen?

Figure 2. Rate of Land Development vs. Population Growth

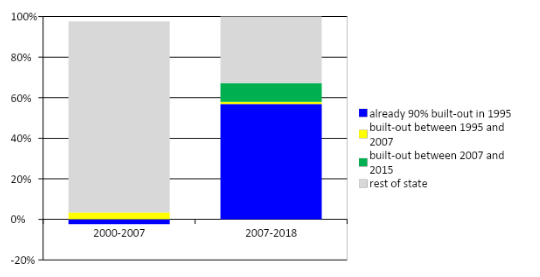

The decrease in newly-developed acres per new resident happened largely because of the channeling of growth back into older cities and towns; when new people move into a place that was already mostly developed, and new development happens by reusing previously-developed land, the amount of newly-developed land per new resident is essentially zero. Prior to 2007, municipalities that were already at least 90 percent built-out 2 (that is, had developed at least 90 percent of their developable land, with most of the remaining undeveloped land being either permanently preserved or undevelopable due to regulation) were mostly stagnant or actually losing population. But built-out places have dominated growth since the Great Recession3, with municipalities that were at least 90 percent built-out as of 2015 accounting for two-thirds of the state’s population growth between 2007 and 2018 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: % of Total Population Growth Accounted For By Built-Out (≥ 90%) Municipalities, 2000-2007 vs 2007-2018

How does new population (and job) growth happen in places that have little or no buildable land remaining? What does “redevelopment” actually look like on the ground? The answer often depends on what kind of development is already in place.

Infill on surface parking lots

Many places have more buildable land remaining than they realize, even if most of it is technically “developed.” “Developed” does not always imply the presence of buildings or other structures; sometimes it simply means “paved.” Surface parking lots represent a de facto land bank for many less densely-developed towns, offering opportunities for infill development between existing buildings, especially if parking structures can be constructed to retain parking capacity but with a smaller two-dimensional footprint. If the existing development pattern is already mixed-use and walkable, infill projects can be designed to harmonize with their surroundings. If the existing pattern is more car-oriented or dominated by a single land-use type, infill projects can offer a chance to create pedestrian amenities and to add land uses or housing types that are currently missing.

Some New Jersey examples include:

- A new seven-story mixed-use complex in Woodbridge, planned for the site of a strip mall and parking lot adjacent to the Woodbridge train station

- Woodmont Metro in Metuchen, an apartment complex with a new public plaza and new parking structure, built on a former commuter parking lot adjacent to the Metuchen train station, that will help diversify the borough’s housing stock, which was previously dominated by single-family detached homes

- Voorhees Town Center, formerly known as Echelon Mall, was a more extensive adaptation, where not only was some of the surface parking replaced with new townhouses, a short restaurant row, and a pedestrian plaza, but part of the mall itself was also knocked down to make room for the new uses

Adaptive reuse of existing buildings

One way to absorb new residents into a built-out place that results in minimal visual change to the existing landscape is by converting non-residential buildings into housing, whether it be an old factory, an office building, a church, or some other obsolete land use. Or a building can be converted to offices or some other use for which it was not initially designed. This can happen even in the most densely developed places, because there is no need to squeeze in any new buildings—the existing buildings have already claimed the space.

Some examples include:

- Luxe Apartments, adjacent to Woodbridge Center Mall in Woodbridge, where an office building is having the upper floors converted to luxury apartments

- Edison Village in West Orange, a complex of historic factory buildings that have been converted to apartments, with a retail component and open green spaces, with townhomes to be added later

- The Vault, an old bank building in Red Bank that has been converted to office space

- Office buildings in Newark that have been converted to apartments: Walker House, Eleven 80

Building a whole new neighborhood on a large derelict site

Occasionally, a single property with a very large footprint—e.g. a factory complex, warehouse, golf course, suburban office park, or shopping mall—will become economically obsolete and go vacant, with little prospect of attracting new occupants. If the existing buildings don’t easily lend themselves to adaptive reuse, it may be more feasible for a developer to simply demolish the old land use entirely and treat the land as a clean slate for building what amounts to a whole new neighborhood. If done in the context of a surrounding environment that is largely car-dependent, this blank canvas can even present the opportunity to create a mixed-use town center in a municipality that previously lacked one, although such a situation can result in a self-contained pod of “modular urbanism” with limited connection to adjacent development. (Suburban, car-oriented land uses were often designed to have limited points of access to and from their surroundings, so connectivity can be difficult to weave in after the fact.) If done in the context of a surrounding street grid with good connectivity, the existing grid can be extended onto the redevelopment property, creating new vehicular and pedestrian connections and allowing for shorter local trips.

Some examples include:

- Wesmont Station in Wood-Ridge transformed the site of a former Curtiss-Wright airplane factory into a new transit-oriented neighborhood, complete with a new NJ Transit commuter rail station

- East Brunswick is planning to create a new town center on the site of an obsolete shopping center

- The District at 1515 project in Parsippany will bring a mix of residential and retail uses, connected by a walkable internal street grid, to the site of a former office park

An empty General Motors plant in Ewing has been cleared to make way for the new Ewing Town Center

The common theme uniting these projects is reuse—reuse of buildings, reuse of land, reuse of infrastructure—which puts the “re-” in “redevelopment.” Any time new residents or businesses can be absorbed into a place that has already been developed—whether through adaptive changes to existing buildings or the construction of new buildings on land that was previously used for something else—this translates to undeveloped land in some other location that does not need to be urbanized to accommodate these residents and businesses, thereby slowing the rate at which New Jersey consumes its remaining open spaces. It also usually means the new development can take advantage of infrastructure that is already in place—roads, power lines, water and sewer pipes—avoiding the costs of extending infrastructure into undeveloped territory.

Redevelopment isn’t just about avoiding the costs associated with new development on previously-undeveloped land, however. It can often also represent an opportunity to make incremental improvements to the existing built environment in which a redevelopment project is situated, by updating the architectural features of an existing building, or introducing a building type or civic function that was previously lacking, or adding to the variety of the town’s housing stock, or creating pedestrian connections and amenities to make the neighborhood more walkable, or providing needed urban open space, or enabling more people to live near public transit and cut back on their driving and car ownership. And when a non-residential building is adapted to residential use, or a formerly industrial land use is cleared and replaced with new residential development, population growth can take place without displacing existing residents, which is often a concern in high-demand urban areas with no buildable land left. Redevelopment is a way to add new housing supply to built-up areas, helping to alleviate upward pressure on housing prices. It can accomplish population change via a net new addition, rather than by the replacement of long-time residents with new ones.

Whatever form it takes, redevelopment can simultaneously enhance livability for existing developed places while allowing other lands to remain undeveloped. Redevelopment will be an essential tool for New Jersey’s municipalities to make an economic comeback. New Jersey Future will continue to partner with towns across the state to create stronger and more integrated places.

1 The DEP data have been produced at irregular intervals since 1986, with data points for 1986, 1995, 2002, 2007, 2012, and 2015

2 Build-out percentage is computed as a ratio of developed acres to total developable acres, where developable land is the sum of 1) already-developed land and 2) undeveloped land that is still available for development. It answers the question “How much of what can be developed has been developed?” Acreage still available for development is estimated by researchers at Rowan and Rutgers universities by overlaying the DEP Land Use/Land Cover data with other data sources that describe lands that have been permanently preserved or are otherwise regulated and cannot be developed. “Available” lands are what remains when undevelopable lands and already-developed lands are both filtered out.

3 Among the data reference years for which DEP land use/land cover data were produced, 2007 comes closest to coinciding with the Great Recession.

Related Posts

Tags: New Jersey, Redevelopment