New Jersey Future Blog

Maximizing the Impact of Public-Private Partnerships

March 30th, 2018 by New Jersey Future staff

This article was written by Elsa Leistikow, a recent graduate of The College of New Jersey with a major in sociology and a minor in public policy.

“Public-private partnerships are not free money.”

“Public-private partnerships are not free money.”

That’s the first point Stephanie Gidigbi, director of NRDC’s Strong, Prosperous and Resilient Communities Challenge (SPARCC), made in the Power of P3s session at New Jersey Future’s 2018 Redevelopment Forum.

Her comments were met with broad concurrence from the rest of the panel, including Dawn Zimmer, former mayor of Hoboken, and Chris Paladino, president of the non-profit New Brunswick Development Corporation. Although these partnerships might look like a panacea to cash-strapped municipalities, Gidigbi emphasized, P3s are not mechanisms for free outsourcing from the private sector. As in any redevelopment project or social service delivery program, aligning conflicting incentives among municipalities, developers, and financiers to deliver a focused, effective outcome is a challenging process.

One theme throughout the panel, which was thoughtfully moderated by David Zimmer, president of the New Jersey Environmental Infrastructure Trust, was the belief that public-private partnerships should maximize community benefit. After a municipality, developer, or financier identifies an unmet need, soliciting community input to inform the project’s objectives and prioritizing these in all aspects of the P3 – from redevelopment design to the contract terms – is crucial, former Mayor Zimmer stated.

Stephanie Gidigbi and Dawn Zimmer made it clear they believed “governments must take the lead” in managing public-private partnerships. When governments direct the project, they said, the “community vision is put first, not just the developer’s.” The city of Hoboken navigated this dynamic when seeking to build a flood mitigation park through a P3. As is common in climate-change mitigation infrastructure, the park required a sizeable initial investment, which would pay off over time in economic terms, public health, and community strength. At first, the city’s partner developer balked at the cost of stormwater infrastructure, but once Hoboken conducted a cost-benefit analysis demonstrating the payoff, the developer consented to the design.

Paladino, whose non-profit development corporation is largely credited with New Brunswick’s physical revitalization, and Gidigbi, who has worked at federal, state, and local levels, each encouraged P3 project managers to “push the envelope in the visioning process.” In particular, Gidigbi encouraged governments to include community revitalization needs in P3 contracts, à la the Pay for Success model. For instance, in 2014, when Prince George’s County, Maryland, created a P3 with Corvias Solutions to build green infrastructure, the county built a contract with incentive payments tied to targets for working with county residents and subcontracting with small disadvantaged businesses. By the start of the project’s third year, incentive payments required that county residents complete 30 percent of the total project hours, and that 40 percent of total project expenditure to be spent through subcontracts with small, disadvantaged businesses, half of which had to be based in Prince George’s County. If Corvias Solutions failed to meet the targets, the company would not receive full payment.

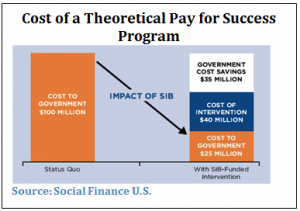

Pay for Success programs, also known as social impact bonds, are public-private partnerships that fund preventative social services at a reduced cost to government. In this model, private investors, such as philanthropies and banks, provide up-front capital to service providers who are charged with delivering a specific social outcome, such as reducing recidivism among a certain population in a city by a certain percent. If the service providers deliver the agreed-upon impact, the government compensates the funders. As one would expect, investing in prevention brings significant cost savings to governments over the long term. So far, Pay for Success programs have delivered successful outcomes for social service, health care, housing and education programs. In the United States, the state of Massachusetts, Cuyahoga County, Ohio, New York City, Denver, Salt Lake City and Chicago, among others, have developed Pay for Success public-private partnerships.

Pay for Success programs, also known as social impact bonds, are public-private partnerships that fund preventative social services at a reduced cost to government. In this model, private investors, such as philanthropies and banks, provide up-front capital to service providers who are charged with delivering a specific social outcome, such as reducing recidivism among a certain population in a city by a certain percent. If the service providers deliver the agreed-upon impact, the government compensates the funders. As one would expect, investing in prevention brings significant cost savings to governments over the long term. So far, Pay for Success programs have delivered successful outcomes for social service, health care, housing and education programs. In the United States, the state of Massachusetts, Cuyahoga County, Ohio, New York City, Denver, Salt Lake City and Chicago, among others, have developed Pay for Success public-private partnerships.

Whether negotiating public-private partnerships to redevelop property, build infrastructure, or contract for social outcomes, Gidigbi cautioned governments to hold tight to their land. “After your people,” she said, “this is your most valuable asset.” As Dag Detter and Stefan Folster describe in The Public Wealth of Cities, far from being broke, local governments are sitting on “goldmines of assets,” with “huge amounts of real estate under their control, as well as … public transit and utilities, and in some cases, ports and airports.” As Redevelopment Forum keynote speaker Bruce Katz writes in a review of the book, by developing P3s for those assets – with public ownership and professional, private-sector management – governments can realize their “enormous untapped wealth,” which they can use to make long-term investments in infrastructure, real estate development, social development and human capital. In the 1990s, Copenhagen financed a citywide transportation system and revitalized its waterfront – without raising taxes – by leveraging the value of its land in a P3.

Panelists Paladino, Dawn Zimmer, and Gidigbi noted that P3s are not the best structure for every redevelopment venture. Former Mayor Zimmer pointed out that “sometimes you just need to get the project done;” investing governments’ limited resources in drawn-out contract negotiations can be inefficient.

However, when the fundamentals are present – community input, public support, focused governments, and committed participants – public-private partnerships can deliver significant benefits. The synergy generated by directing diverse organizations and departments’ perspectives, talents, and resources towards a single goal, Paladino confirmed, can make the challenges of aligning incentives and prioritizing community benefit truly worthwhile.