New Jersey Future Blog

Symposium Addresses Dangers of Inaction on Climate Change

October 18th, 2017 by Emily Eckart

Memories of Hurricane Sandy loomed large at New Jersey Future’s The Shore of the Future symposium

“Dealing with Sandy was a nightmare for us,” said John Spodofora, mayor of Stafford Township and one of 11 panelists at the event. More than 4,000 homes in Stafford were severely damaged by the 2012 hurricane, totaling $200 million in property damage. The town lost millions in tax revenue. Spodofora remembered that many residents came into town hall crying, unsure where they were going to live. Five years later, only 65 percent of Stafford Township is rebuilt. The most difficult areas to rehabilitate make up the 35 percent that have still not recovered.

“Dealing with Sandy was a nightmare for us,” said John Spodofora, mayor of Stafford Township and one of 11 panelists at the event. More than 4,000 homes in Stafford were severely damaged by the 2012 hurricane, totaling $200 million in property damage. The town lost millions in tax revenue. Spodofora remembered that many residents came into town hall crying, unsure where they were going to live. Five years later, only 65 percent of Stafford Township is rebuilt. The most difficult areas to rehabilitate make up the 35 percent that have still not recovered.

The Oct. 17 Shore of the Future symposium was centered on having a “big conversation” about the need for a regional approach to coastal resilience in the face of climate change. Although New Jersey has made some progress since the hurricane, the state has not yet organized a concerted effort to mitigate risk and adapt to rising sea levels. Approximately 200 attendees gathered at the Trenton War Memorial to hear from 14 experts across a wide range of fields.

A few key themes emerged from the panelists’ comments. First, a regional approach is necessary. Municipalities do not have the resources to devote to large-scale planning and hazard mitigation. Local governments are often occupied with day-to-day issues that affect their constituents, and they rely on immediate revenue sources. A regional body would be better positioned to create a broad, long-term plan. New Jersey already has models of this type of structure in the former Meadowlands Commission, the Pinelands Commission and the Highlands Council.

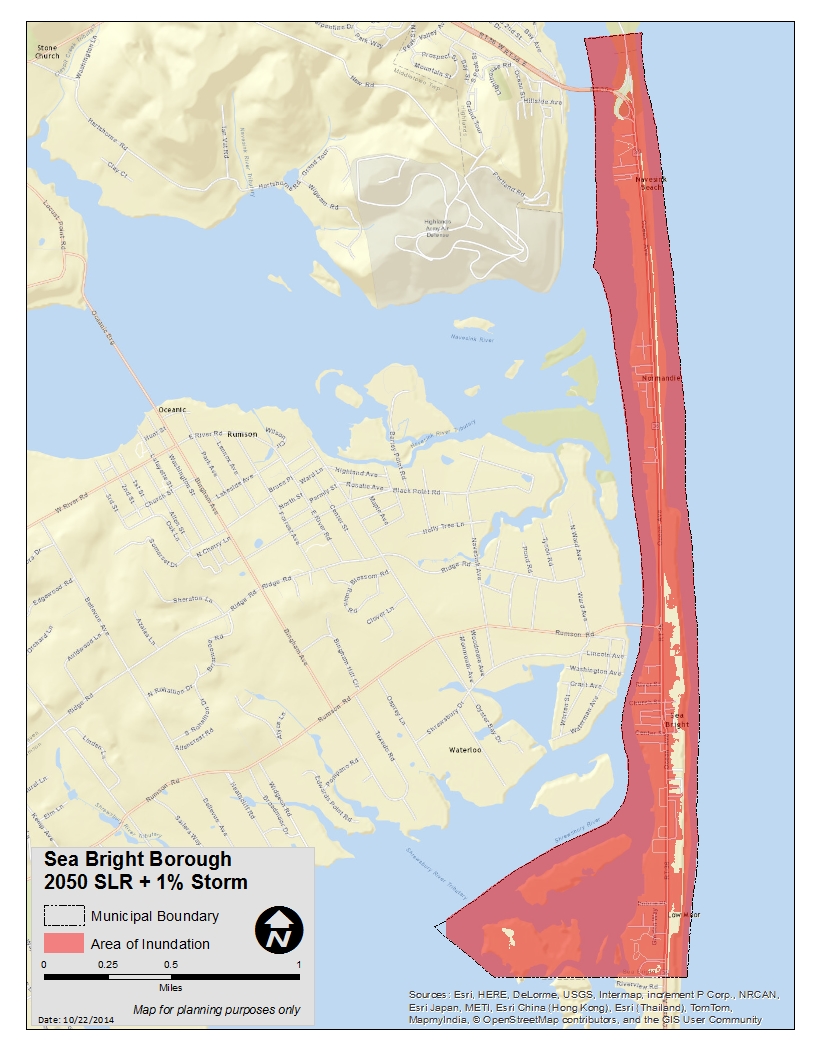

Second, any plan must incorporate science into its policies. Jeanne Herb of the Rutgers Climate Adaptation Alliance emphasized the importance of collecting data to determine where to spend public dollars on infrastructure, where to allow or incentivize development and redevelopment, and how to work with communities to implement policies. Science should not be an afterthought, but a framework for sound policy.

Third, it is increasingly apparent that natural resources must be a component of any climate adaptation and mitigation strategy. Spodofora observed that most of the damage Hurricane Sandy inflicted on Stafford Township occurred in areas that were not protected by natural berms. Similarly, the American Littoral Society’s Tim Dillingham said, “Wetlands are called wetlands for a reason: It’s where the water wants to go.” Wetlands help mitigate the impact of storm surges. As former Meadowlands Commission Executive Director Robert Ceberio said, they should be seen not as development opportunities, but natural assets. To this end, the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection has partnered with Stevens Institute of Technology to develop engineering guidelines for living shorelines.

Fourth, equity should be a part of any climate change plan. Herb noted that a diverse population makes use of the Jersey Shore. Some of the most devastating impacts of Hurricane Sandy affected communities that are underrepresented in decision-making bodies. An adequate plan will account for input from these stakeholders and make sure that any outcomes are equitable.

Fifth, communicating risk is a complex, delicate and time-consuming task, but it must be mastered. New Jersey Future’s David Kutner talked about a survey done in several shore towns that showed how unwilling many residents were to talk about the need for large-scale changes to their towns or their way of life, noting that it is only now, five years later, that some residents are beginning to acknowledge that the future will look very different from the past. Communication timing was also highlighted; New Jersey Climate Adaptation Alliance’s Jeanne Herb noted that if residents in hard-hit areas had been asked immediately after Sandy about having their properties bought out, their answers would have been very different than after they had done extensive renovation work and moved back in. Effective communication of risk must be personal, showing how dangers will affect individual residents, and hopeful, providing options that allow residents to retain a sense of control over their relocation decisions.

Finally, financial matters are a reality of preparing for climate change. As Spodofora pointed out, financial impact from storms comes not only from physical damage, but also from lost tax revenue. Buyouts of homes can be a solution for flood-prone areas, but municipalities must cope with the implications of lost revenue. Innovations such as tax revenue sharing, and politically difficult decisions such as consolidation of townships, may be necessary as future buyouts of homes occur. At the same time, companies like Moody’s are accounting for climate change risks when they develop ratings for investors, affecting economic development prospects. Willis Towers Watson’s Samantha Medlock noted that insurance and reinsurance companies are in a position to work with state and regional players to advance short-term resilience.

Panels Addressed What’s at Stake, Where We Need To Go

The first panel was moderated by Shana Udvardy from the Union of Concerned Scientists. Udvardy asked five panelists to share some background information on climate change and how it could affect New Jersey’s residents, businesses, and infrastructure. Liz Semple, manager of the Office of Coastal and Land Use Planning at New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, pointed out that the state has $145 billion worth of assets in areas that could flood at current sea levels—a danger echoed by Mayor Spodofora’s reflections on Hurricane Sandy. Edward Lloyd, the Evan M. Frankel Clinical Professor in Environmental Law at Columbia Law School, emphasized that we cannot avoid consequences of climate change, but that they can be mitigated if New Jersey commits to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by moving toward renewable energy. Jeanne Herb of the New Jersey Climate Adaptation Alliance advocated for the importance of creating policy based on science, while Tiphany Lee-Allen, a vice president at Moody’s Investors Service, provided a financial perspective. A member of Moody’s environmental, social, and governance task force, Lee-Allen noted that the company incorporates environmental risks into its analysis when they have the potential to affect probability of default and/or loss given default. Some of Moody’s methodology scorecards explicitly score environmental risks.

The first panel was moderated by Shana Udvardy from the Union of Concerned Scientists. Udvardy asked five panelists to share some background information on climate change and how it could affect New Jersey’s residents, businesses, and infrastructure. Liz Semple, manager of the Office of Coastal and Land Use Planning at New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, pointed out that the state has $145 billion worth of assets in areas that could flood at current sea levels—a danger echoed by Mayor Spodofora’s reflections on Hurricane Sandy. Edward Lloyd, the Evan M. Frankel Clinical Professor in Environmental Law at Columbia Law School, emphasized that we cannot avoid consequences of climate change, but that they can be mitigated if New Jersey commits to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by moving toward renewable energy. Jeanne Herb of the New Jersey Climate Adaptation Alliance advocated for the importance of creating policy based on science, while Tiphany Lee-Allen, a vice president at Moody’s Investors Service, provided a financial perspective. A member of Moody’s environmental, social, and governance task force, Lee-Allen noted that the company incorporates environmental risks into its analysis when they have the potential to affect probability of default and/or loss given default. Some of Moody’s methodology scorecards explicitly score environmental risks.

Matt Fuchs, an environment officer at Pew Charitable Trusts, moderated the second panel. The panelists included Robert Ceberio, president of RCM Ceberio LLC and former executive director of the Meadowlands Commission; Tim Dillingham, executive director of the American Littoral Society; Robert Freudenberg, vice president of energy and environmental programs at the Regional Plan Association; David Kutner, planning manager at New Jersey Future; Joseph J. Maraziti Jr. Esq., partner at Maraziti Falcon LLP and a trustee of New Jersey Future; and Samantha A. Medlock, senior vice president and North America lead for capital, science, and policy practice at Willis Towers Watson.

Matt Fuchs, an environment officer at Pew Charitable Trusts, moderated the second panel. The panelists included Robert Ceberio, president of RCM Ceberio LLC and former executive director of the Meadowlands Commission; Tim Dillingham, executive director of the American Littoral Society; Robert Freudenberg, vice president of energy and environmental programs at the Regional Plan Association; David Kutner, planning manager at New Jersey Future; Joseph J. Maraziti Jr. Esq., partner at Maraziti Falcon LLP and a trustee of New Jersey Future; and Samantha A. Medlock, senior vice president and North America lead for capital, science, and policy practice at Willis Towers Watson.

The program concluded with a keynote address from Joseph P. Riley Jr., who served as mayor of the City of Charleston, South Carolina, from 1975 to 2016. Mayor Riley spoke about how he enacted changes that made Charleston more adaptable to flooding. When he was first elected to office, there were parts of the city that flooded regularly—places where “cars would float.” He decided to create a comprehensive drainage master plan to address the problem. First, he had the city and its drainage spaces mapped. He then worked to introduce a stormwater utility fee, South Carolina’s first. Mayor Riley emphasized that it is sometimes necessary to raise taxes, pointing out that the public is willing to pay more if elected officials explain the reasons and the benefits clearly. He planned tax increases with the long-term future in mind. For instance, in his last two years in office, he created another comprehensive plan for dealing with sea level rise. The plan would require more money, which would be raised through another tax increase. Knowing that the next mayor couldn’t afford politically to increase taxes immediately upon assuming office, Mayor Riley worked to make the change take place during his own final term. He balanced the new taxes with reductions in other areas, resulting in a lower overall tax burden for residents. Additionally, he got money from the state and federal governments for projects such as a $140 million drainage improvement project.

The program concluded with a keynote address from Joseph P. Riley Jr., who served as mayor of the City of Charleston, South Carolina, from 1975 to 2016. Mayor Riley spoke about how he enacted changes that made Charleston more adaptable to flooding. When he was first elected to office, there were parts of the city that flooded regularly—places where “cars would float.” He decided to create a comprehensive drainage master plan to address the problem. First, he had the city and its drainage spaces mapped. He then worked to introduce a stormwater utility fee, South Carolina’s first. Mayor Riley emphasized that it is sometimes necessary to raise taxes, pointing out that the public is willing to pay more if elected officials explain the reasons and the benefits clearly. He planned tax increases with the long-term future in mind. For instance, in his last two years in office, he created another comprehensive plan for dealing with sea level rise. The plan would require more money, which would be raised through another tax increase. Knowing that the next mayor couldn’t afford politically to increase taxes immediately upon assuming office, Mayor Riley worked to make the change take place during his own final term. He balanced the new taxes with reductions in other areas, resulting in a lower overall tax burden for residents. Additionally, he got money from the state and federal governments for projects such as a $140 million drainage improvement project.

‘We Have a Duty to the Future’

To emphasize the importance of acting now to protect the shore and all it represents to New Jersey, Riley told a story about a flight he took from South Carolina to New Hampshire. The airplane stopped in Cape May to refuel and flew north along the New Jersey coast. He admired the sparkling rivers, inlets, and bays. He was struck by the beauty of the pines and the sandy shores. “It was absolutely breathtaking, and still vivid in my memory as an extraordinary natural resource,” Riley related. It was a resource too precious to waste. “We have a duty to the future,” he said. Change is difficult, but the alternative is too costly to consider. “It is our responsibility to take action before it’s too late.”

Correction: 10/23/17 – An earlier version of this article stated that Moody’s is starting to incorporate climate change and environmental risk in its ratings. Actually, Moody’s has already incorporated these risks into its ratings for some time. Environmental risks are incorporated into the analysis when they have the potential to affect probability of default and/or loss given default. Additionally, an earlier version stated that Samantha Medlock mentioned the importance of timing in property buyouts. It was Jeanne Herb who made the point about timing of buyouts after Sandy.