New Jersey Future Blog

Explainer: How to Think About New Jersey’s Population (and Income) Growth

September 14th, 2016 by Tim Evans

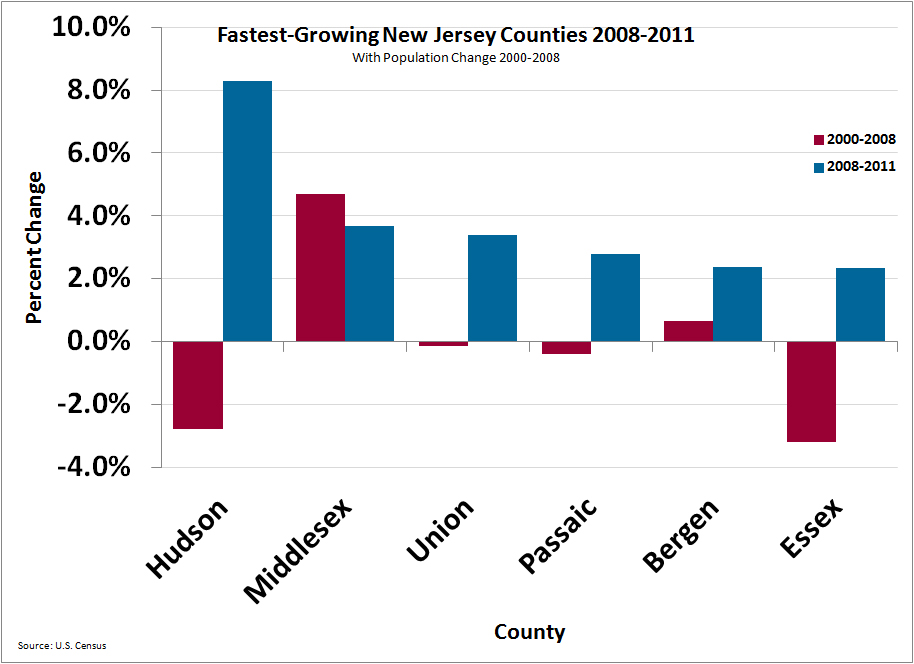

As an organization dedicated to using our land wisely, New Jersey Future has a great interest in whether the state’s population is increasing or decreasing, and by how much, and in what parts of the state. A rapidly increasing population means increasing development pressures on our towns, cities and remaining open spaces, while a declining population raises questions about what to do when economic and demographic changes render an industry or a development type obsolete. Both scenarios have implications for infrastructure investment priorities and place-based growth incentives. Therefore, it is important to understand the full picture of population growth or decline in our state.

Other policy organizations are interested in making the connection between population growth and state tax revenue growth. While tax policy is normally outside of New Jersey Future’s purview, the state’s ability to raise funds to pay for the maintenance and expansion of core infrastructure is of great importance. Additionally, growth and development policies and priorities will differ depending on whether population and tax revenues are projected to increase or decrease in the future.

There has been some confusion recently about whether New Jersey has been gaining or losing population in recent years (answer: It’s still gaining), and about the effects of population change on the state’s tax revenues. The confusion likely arises from the fact that two recent reports – one from the New Jersey Business and Industry Association (pdf) and one from New Jersey Policy Perspective – are focused mainly on people moving out of New Jersey, which is only one piece of the total population-change picture.

Population Change

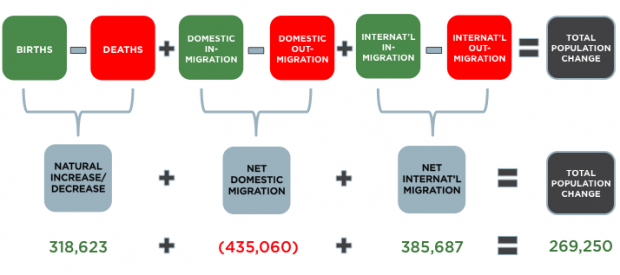

New Jersey’s (or any state’s) total population change over a given time period can be expressed as a combination of six components, some of which represent additions to the baseline population (shown in green) and some of which represent subtractions (shown in red). To simplify the equation further, the six components can be reduced to three by pairing up three sets of related components.

According to the Census Bureau, between 2004 and 2013, New Jersey had a net natural increase of 318,623 people, a net domestic migration loss of 435,060 people, and a net international migration gain of 385,687 people, resulting in an overall increase in the state’s population during this time of 269,250.

Natural Increase/Decrease

Natural increase/decrease is measured by subtracting the number of deaths from the number of births. In rare cases, the number of deaths exceeds the number of births, resulting in a natural decrease. This sometimes happens in rural counties whose young people are migrating to metropolitan areas and not sticking around to have babies within the county, while older residents continue dying off. In New Jersey, the number of births has continued to outpace the number of deaths, so this difference is a net positive or a natural increase.

Net Domestic Migration

Net domestic migration is calculated by subtracting the number of domestic out-migrants from the number of domestic in-migrants. When the number of people moving out to other states is bigger than the number of people moving in from other states, as it has been for New Jersey (and most of the rest of the Northeast) for many decades, then the result is a net out-migration; i.e., the difference between the two components is a negative number.

Net International Migration

Similar to domestic migration, net international migration is calculated by subtracting the number of international out-migrants from the number of international in-migrants. For most states, and particularly immigrant destination states like New Jersey, this difference is normally positive (i.e., a net inflow), since the number of Americans moving to other countries is generally much smaller than the number of people moving to the United States from elsewhere in the world.

State Revenue

How is population growth related to state revenue growth? In theory, each of these population components has income associated with it, although the NJPP study runs through numerous arguments for why the incomes of individual out-migrant households do not necessarily add up to what happens to total tax receipts at the macro level. (For example, when a person moves out of New Jersey but a new person moves in to take that person’s job, for the same salary, has the out-migrant’s income really left the state?) But let us assume for the moment that looking at the incomes associated with the households comprising the various components of population change yields, to the extent possible, a somewhat accurate picture of “income migration.” What do we know about the relative sizes of those components?

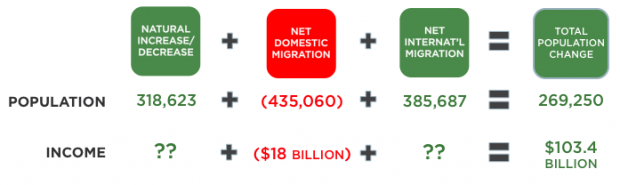

Consider population change first. From 2004 to 2013,1 the time frame being studied by the NJBIA and NJPP reports, New Jersey’s population change breaks down as described above, resulting in a net positive number of almost 300,000.

What about the incomes earned by these different groups? The NJBIA report uses IRS data to assert that New Jersey’s net domestic outflow of residents from 2004 to 2013 took a net $18 billion with it: “From 2004-2013, New Jersey lost $18 billion in net adjusted gross income.” This is the only individual component of population change to which either the NJBIA study or the NJPP study attached an income figure. However, this single statistic tells only part of the migration story – the net domestic out-migration part. It ignores the state’s natural increase, and it ignores immigrants from other countries, and the income (and, by extension, the tax revenue) generated by these two groups.

We do not know the actual values of the incomes generated by the other two components of population change because neither study undertook to compute them. But we do know, from the NJPP study, that New Jersey’s total reported income grew by $103.4 billion between 2004 and 2013. To calculate this, the NJPP study retrieved, from the same IRS data source used by the NJBIA study, data on total adjusted gross income reported by all households in 2013 ($319,093,488,000) and in 2004 ($215,694,524,000) and computed the difference: $319,093,488,000 – $215,694,524,000 = $103,398,964,000.

This $103.4 billion figure is the analog to the total population increase of 269,250 from the population-growth equation. (Incidentally, note that the $103.4 billion increase in total adjusted gross income represents a 47.9 percent increase over the 2004 income total, as compared to population growth of only 3.4 percent2 over the same time period. Whatever the explanation, and however much income may have “migrated” out of New Jersey, the state’s growth in total income nonetheless outpaced population growth by a factor of more than 10 over the time period studied by NJBIA and NJPP.) So we can construct an income analog to the population-change equation, albeit with two pieces whose precise values are unknown:

Clearly, while the exact numbers haven’t been computed, the sum of the collective incomes corresponding to the other two components – natural increase and international immigration – must be positive, because otherwise it is impossible for the three components to add up to a net increase of $103.4 billion in the total amount of income reported. In fact, we can infer that the sum of natural increase and net international immigration income increases over this time period should total approximately $121 billion dollars. To summarize, during the period of 2004-2013, New Jersey received approximately $121 billion of new taxable income and lost $18 billion, suggesting a net increase of $103.4 billion. A net increase in the state’s taxable income during this period has very different policy implications than would an implied loss.

The NJBIA study observes that “(a)s New Jerseyans leave the state they not only take their income with them, but they take income taxes, sales taxes, property taxes, and purchasing power with them as well.” This may be true, but it is also true that people moving into New Jersey from other states and from other countries bring their financial profiles with them. And New Jersey’s natural population increase also contributes its share of income growth, by creating a stream of new workers that is more than sufficient to replace those who die off. Only by accounting for the tax revenues generated both by international immigrants and by the increase in the number of people who were born and raised here do we get a complete and accurate picture of New Jersey’s fiscal health. Any decisions being made about tax policy, particularly those that affect infrastructure spending and economic incentives, should be made with the entire picture of New Jersey population growth in mind and should not focus narrowly on domestic out-migrants.

[1] There is a nine-month gap in the Census Bureau’s published data between July 1, 2009 and April 1, 2010, because data on components of population change (which are estimated for the one-year period ending on July 1 of each year) for the 2000s run only to 2009, while the data for the 2010s pick up on Census day (April 1) of 2010. The totals cited here are computed by summing the various components from July 1, 2004 through July 1, 2009 and from April 1, 2010 through July 1, 2013 and will thus be slight underestimates of the true values because of the missing nine months. In contrast, the official annual Intercensal Estimates of state populations contain no such gaps but include total population only. This data gap, as well as methodological differences between the components-of-change estimates and the official state population estimates, accounts for the discrepancy between the total 2004-to-2013 population change of 269,250 cited here and the slightly larger figure of 295,854 that results from taking the difference between the official annual estimates for the two years. Back to article.

[2] Computed using the difference of 295,854 between the official state population estimates for the two years, as described in the previous footnote.Back to article.

Tim – Nice and more importantly accurate depiction of the fiscal picture in NJ.

Brian Slaugh

Great clarification on in/out migration income impact. For this analysis to be totally useful it must include the amount of state entitlements/expenses required by the in-migrants versus the amount no longer required by the out-migrants.

By way of an example, if 10 people out-migrate, taking $10 million of income and leaving $0.5 million of entitlements/expenses, and are replaced by 20 people in-migrating, bringing $0.5 million of income and requiring $1 million of entitlements/expenses, the total positive population change results in a negative change to net income.

I agree with your statement that “the state’s growth in total income nonetheless outpaced population growth by a factor of more than 10;” however it is my opinion that net income should be the better measurement of the financial impact of net migration results.

I do enjoy the hyperbole of chambers and others in the political arena as they make the point…but in a way that so stretches the truth that the point is lost. What still matters is that the total growth is still significantly below natural increase. I take that as both an environmental challenge (where they go creates larger negative effects than if they were here) and a missed economic/fiscal opportunity for us. There are reasons housing leads other states out of recessions…but not here. We need to do better.

Creigh — I made a similar point during the Q&A period at NJPP’s event that they held around the time that the two reports were released. I asked why legislators seemed to immediately leap to the conclusion that NJ’s net domestic out-migration was due to the income tax or the estate tax chasing high-income people out of the state, when, in my opinion, the MUCH more likely explanation is high property taxes and high home prices (caused by an artificially constricted supply) chasing MIDDLE-income people out of the state. I asked (rhetorically) if out-migration is only a problem if it’s rich people who are leaving. Many in the audience seemed to appreciate my question!

Good point! I’d love to convince you it has something to do with the supply of relevant zoning as well. At critical points we have been unable to provide the housing types needed. For all of our outmigration, we still maintain a below-structural level of vacancy. No matter what the people leaving say they were thinking, it turns out that the number leaving are the number that had to leave given our tepid housing production.

With the number of affordable housing settlements which will create a greater supply of multi-family zoning, it will be interesting to see if the production of housing increases commensurately.