New Jersey Future Blog

Upward Economic Mobility Is a Land-Use Issue

August 2nd, 2013 by Elaine Clisham

Reducing Income Inequality Can Enhance Economic Prosperity for All

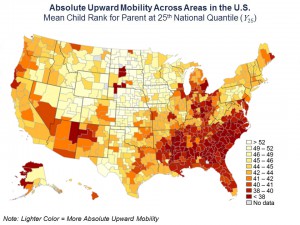

An interesting new study by a team of economists from Harvard and Berkeley shows a significant correlation between certain factors related to land use and the ability of children born into the lowest income levels to move into the middle class.

An interesting new study by a team of economists from Harvard and Berkeley shows a significant correlation between certain factors related to land use and the ability of children born into the lowest income levels to move into the middle class.

The economists, who set out to study the degree to which tax relief programs such as the Earned Income Tax Credit can help children move out of poverty, found only modest correlation there, but much stronger correlation between economic upward mobility and several other factors.

Nationally, the study found that prospects for economic improvement are hindered when the population in an area is segregated economically; that is, when poorer households are concentrated in areas far from more affluent households, good schools, and middle-class jobs. Long commutes to work from poor areas, especially in the absence of a supportive transit network, further inhibit economic mobility. Conversely, mixed-use, mixed-income communities are associated with greater upward mobility. For example, a person who is poor in Atlanta, according to the study, has greater difficulty moving upward because poor households in the Atlanta area are significantly more segregated from both employment opportunities and higher-income households than in many other areas. (One of the other factors that correlated strongly with higher mobility is increased civic engagement. It’s reasonable to assume that those in poor households who live close to others further up the income ladder may have access to a civic engagement network that can offer more opportunity, and may have more time to take advantage of it, than those in poor households without middle-class neighbors.)

New Jersey generally falls in the middle of the pack in this study, according to additional analysis done by The New York Times: In northern New Jersey, a child born in the bottom income quintile has a 9 percent chance of winding up in the top quintile by the time he or she is 40, placing the area 11th among the 30 most populous of the economic areas defined in the study. In the southern New Jersey area, which includes Philadelphia, the chance is almost 8 percent, placing that area 19th out of the top 30. (By contrast, the lowest-mobility areas in the country had bottom-to-top-quintile economic mobility rates for their children of less than 4 percent, and the highest-mobility areas had rates above 30 percent.)

The strong correlation between the opportunity for children who are poor to grow up in mixed-income communities and their ability to rise to the middle class means that the fortunes of New Jersey’s most disadvantaged residents depend in no small part on every community’s ability to provide access to housing for all income levels. In addition, a growing body of research has found that entrenched income inequality can exert downward pressure on overall economic growth, which means that the degree to which residents who are poorer have access to good schools, good jobs and good civic networks determines at least in part the degree to which our entire state can enjoy robust economic prosperity. Policies that keep housing out of reach to many – zoning that requires large lots, or restricts large areas of a municipality to single-family housing – and incentives that keep jobs and workers at great distance from each other, combine to restrict economic opportunity for some and, in so doing, constrain economic prosperity for all.