New Jersey Future Blog

Targeting Industry and Geography Together to Foster Job Growth

September 12th, 2012 by Elaine Clisham

New Jersey Future Senior Director of State Policy Chris Sturm and summer intern Prachi Sharma are also co-authors of this article.

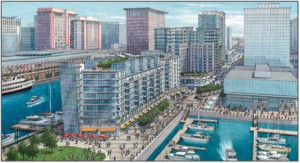

Rendering of the Innovation District on South Boston’s waterfront. Source: Seaport District

New Jersey’s disappointing employment numbers are even more disappointing when industry sectors are examined in detail. Unadjusted numbers show that, for the five industry sectors identified in the draft State Strategic Plan as being key to the state’s future prosperity, July 2012 employment either remained unchanged or declined compared with June:

- Manufacturing lost 3,100 jobs, including 100 jobs from the state’s key pharmaceutical sector; transportation and warehousing lost 4,300 jobs; technology lost 200 jobs; and financial services lost 300 jobs.

- By contrast, the leisure and hospitality sector, where some of the lowest-paying jobs can be found, saw the most growth in July with an increase of 6,600 jobs.

Some of these losses can be attributed to the state of the overall economy. Manufacturing and transportation and warehousing, for example, are expected to pick up as the economy recovers and demand for goods increases.

However, two key categories – the pharmaceutical industry and the technology sector – warrant further discussion, since they are often considered “innovation” sectors: those most likely to bring new products to market, to attract highly educated and highly paid workers, and to grow most rapidly. The job loss in these sectors is not a good trend for a state in which 34.5% of residents 25 and older have at least a bachelor’s degree, the fifth-highest college-education attainment rate in the country. If we cannot provide jobs for these workers, we put our future prosperity at risk.

Competing Cities Adopt “Innovation District” Strategy

In an effort to identify strategies that could help fast-track the growth of these key sectors and simultaneously strengthen host cities, New Jersey Future examined the concept of innovation districts – an economic development approach that aims to catalyze growth in specific locations through partnerships among government, the private sector and higher education. Our new report on the topic, Innovation Districts: A Look at Communities Spurring Economic Development through Collaboration, prepared by 2012 summer intern Prachi Sharma, is an interim examination of four rising districts that might serve as models: New York City’s CornellNYC Tech Campus, Boston’s Innovation District, 22@Barcelona, and Syracuse’s Connective Corridor.

Each of the cities studied based its district on the premise that face-to-face contact among innovators sparks collaboration and new ideas. Boston’s Innovation District seeks to lure young knowledge workers by creating a “Work, Live, Play” environment, including a dynamic mix of uses and start-up housing affordable to young entrepreneurs. Higher education represents a key partner in all of the districts, and perhaps most dramatically in New York where the city attracted a new engineering university by offering access to a development site and $100 million in infrastructure improvement funding. Targeted infrastructure investments in well-connected but underutilized areas has laid the groundwork for private investment; in Syracuse, New York, a public-private partnership garnered over $40 million for roads, transit and pedestrian improvements along its two-mile Connective Corridor. Barcelona, Spain, the longest-standing district, has led the trend to focus on specific industry clusters and to support their growth through dedicated meeting places, incubator facilities and networking organizations.

The importance in these case-study districts of proximity, which facilitates face-to-face collaboration and interaction; robust infrastructure, particularly transit; and the ability to attract and retain highly educated creative-class workers suggests that innovation districts have the best chance of driving growth if they’re fostered in “smart-growth” areas characterized by good pedestrian and transit connections and a closely concentrated mix of land uses.

As the draft State Strategic Plan describes, New Jersey has most of the fundamental assets and institutions necessary for the establishment of such districts: It is home to 31 four-year universities and 19 county colleges with two-year programs, which in the fall of 2011 were educating a total of 442,878 students. It boasts a strong bio/pharmaceutical and life-sciences industry, housing major firms and supported by a highly educated workforce (two-thirds of employees in the life-sciences industry and 63 percent in the technology sector hold at least a bachelor’s degree). Advanced manufacturing, finance, technology, and transportation and logistics are also prominent clusters. And there are strong transit connections both within the state and to New York City and Philadelphia.

However, to remain competitive, New Jersey must focus its investments even more strategically on the right combination of industries, locations, and supporting infrastructure in order to create fertile ground for growth and opportunity while also encouraging responsible land use. Once adopted, New Jersey’s State Strategic Plan should offer a clearer framework for moving such strategies forward.