New Jersey Future Blog

Going the Distance

August 31st, 2005 by Tim Evans

- Annual vehicle miles traveled (VMT) per capita in New Jersey have increased steadily over the past three decades, from about 5,000 miles per year in 1965 to over 8,200 in 2003. In 2003, per capita VMT was 600 miles higher than it was in 1990.

- Because the state’s population has also risen over the same period, the actual miles driven – and pollutants emitted and fuel consumed – have risen at a much higher rate than the per capita figures show.

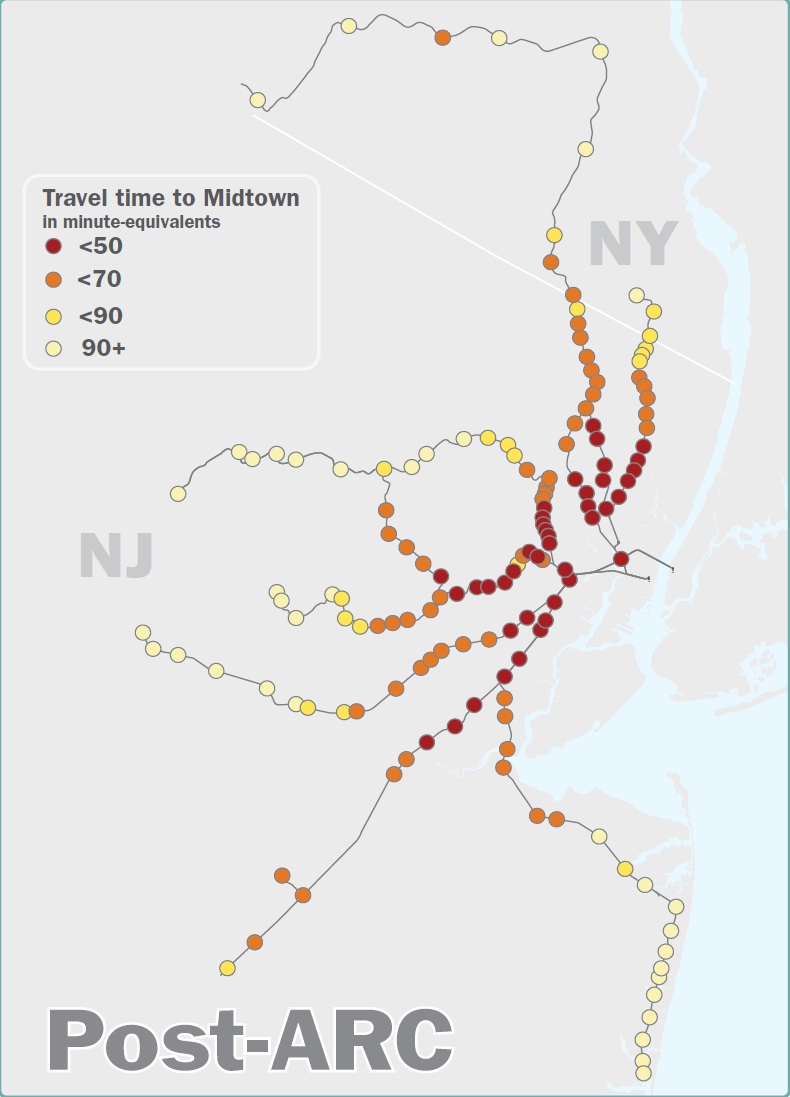

- New Jersey’s average commute time of 30 minutes is the third highest nationally and climbing. Over the past 20 years, employment locations in New Jersey have become much more dispersed. Most of the state’s older job centers have experienced a net loss of jobs.

- The costs of increasing VMT are high. The costs in lost time and excess fuel consumption due to traffic congestion amount to $6.8 billion a year in the greater New York City region, and approach $2 billion in the greater Philadelphia region. Vehicles also take a toll on the environment. Car exhaust is a major source of air pollution, including greenhouse gas emissions. In addition, the impervious surface in roads, driveways, and parking lots increases storm runoff and storm surges, eroding stream banks and increasing water pollution.

(Sources: NJDOT Bureau of Transportation Data Development from the Factbook; 2000 U.S. Census; New Jersey Legislative District Data Book; and The Texas Transportation Institute)

THE ROAD TO NOWHERE

With gas prices at record levels, there is an urgent need for policies that address our automobile dependence. Yet our reliance on cars continues to rise, and this trend shows no sign of slowing down.

New Jerseyans deserve more choices about how to get around, and how much time they spend in their cars. But many New Jerseyans do not have such a choice. Poor local planning fails to create complete communities, where daily activities are close at hand. Too many New Jerseyans need to burn a gallon of gas to get a gallon of milk because of few options besides the car for travel to stores, school, recreation, and work.

Additionally, policies and incentives lure employers away from public transit and increase truck and auto traffic. As employment locations in New Jersey become more dispersed, there are serious implications for traffic congestion and time lost to delays, as well as open land consumed by new office development. Many of the state’s older job centers that are losing jobs are “complete communities” that are walkable and well served by public transit, so job loss in these places – accompanied by job growth in automobile-dependent locations – has the effect of putting more cars on the road because some people who used to be able to walk or take transit to work must now drive.

If New Jersey is to continue to prosper, candidates for state office this fall should look to policies that make it easier for New Jerseyans to get around by increasing housing near employment centers, making town centers the de facto form of municipal planning, encouraging municipalities to allow more intensive development around transit facilities, and creating incentives for employers to locate in pedestrian- and transit-friendly settings.