New Jersey Future Blog

Municipal “Ratables Chase” Doesn’t Necessarily Pay

August 4th, 2010 by Tim Evans

- Conventional wisdom among municipal leaders is that the key to keeping property tax rates down is to discourage residential development in favor of commercial (i.e. non-residential) ratables.

- Towns vary in terms of the breakdown between their residential and commercial tax bases. In the median municipality, the commercial share of the property tax base was 21.4 percent in 2006.

- Among the 57 municipalities with the highest concentrations of commercial properties (more than double the statewide median) the median property tax rate in 2006 was 1.58 percent. But among the 80 municipalities with the highest concentrations of residential properties the median tax rate was even lower at 1.43 percent.

- Of the municipalities that increased the commercial share of their property tax base between 1998 and 2006, six percent saw their property tax rates increase. In contrast, tax rates went up in only 2.5 percent of the towns that saw their tax bases become more heavily residential.

Link Between Commercial Development and Lower Property Tax Rates is Inconclusive

The practice commonly referred to as the “ratables chase,” wherein towns chase after high-value taxable, or “ratable,” properties has long been pursued by municipalities as a strategy for keeping down property tax rates. The theory is that residential development often creates more expense for a municipality in the form of school costs than it generates in property tax revenue, while commercial properties generate tax revenue without a high level of demand for services and, most significantly, no demand for public education (kids don’t live in office buildings). As a result, many municipalities use their zoning power to attract big-box stores, office parks and warehouses, while actively discouraging residential uses (with the exception of senior housing, which creates no additional school costs).

But does it play out this way in reality? Do municipalities with the highest concentrations of commercial properties also tend to have the lowest tax rates?

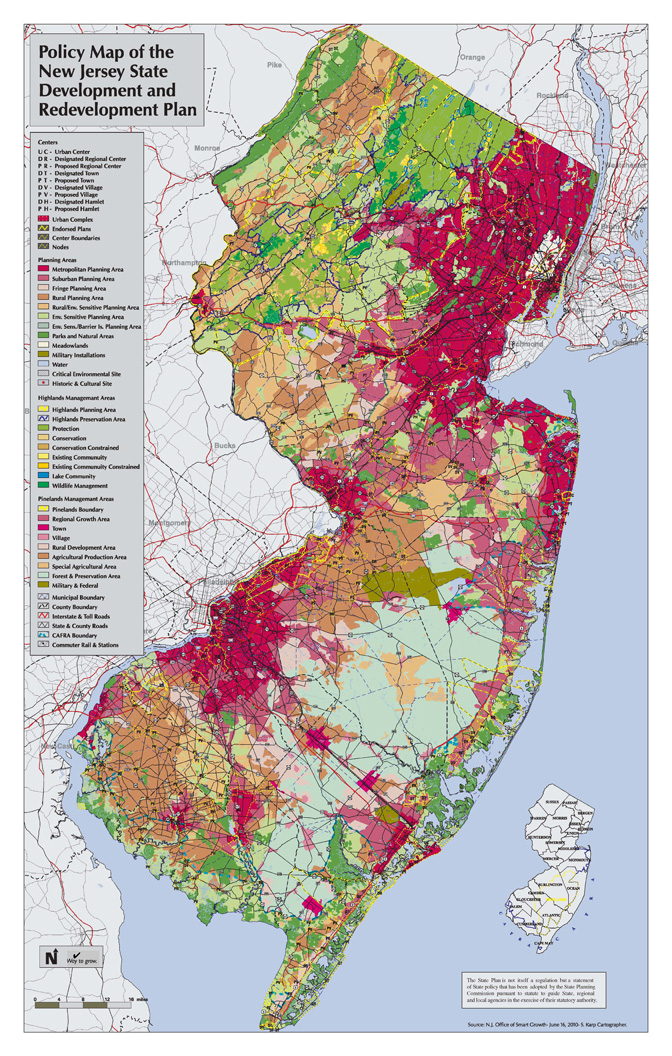

Using data compiled by the New Jersey Legislative District Data Book, New Jersey Future has compared municipalities’ property tax rates with the percentages of their total tax bases that are comprised of commercial property. The results are at best inconclusive, which in itself is newsworthy. Looking at 2006 data, there is no clear indication that a high proportion of commercial property in a municipality’s tax base necessarily corresponds to a lower-than-average property tax rate; in fact, plenty of municipalities illustrate that a low tax rate is possible even with very little commercial property. And the trend over time sheds no further light on the issue: the relatively few municipalities that increased the commercial share of their tax base between 1998 and 2006 did generally see their tax rates go down, but not systematically any faster than their neighbors .

There are numerous reasons why the expected relationship between more commercial property and lower tax rates might have failed to materialize, but whatever the reason, any municipality that thinks the secret to beating its neighbors at the property tax game is to score the next office park or shopping mall should probably take a look at the data first.

For more information, see the full write-up of New Jersey Future’s analysis of the ratables chase and the Daily Record’s companion article giving the local perspective.

In the full sense of the concept, there are very few planned communities in New Jersey. By this I mean areas that have developed and grown in accord with a comprehensive land use plan that accommodates all types of safe and nonpolluting land uses so that residents can live, work and play without having to jump in an automobile to get from point A to point B. One serious consequence is that upwards of 10% or more of the surface land area in many communities is dedicated to the automobile and automobile traffic. The lowest, worst use of valuable land is the surface parking lot; yet, virtually every office building and every strip shopping center and mall is surrounded by huge parking lots rather than far more efficient parking garages. Perhaps the most important reason this occurs is that land assessments are universally set at a fraction of full market value. Thus, there is no financial incentive (i.e., generation of cash flow) to cover the costs of constructing efficient parking facilities.

Whether or not one is convinced by scientists who argue we have reached the peak of oil production and that fossil fuel costs will in the not-to-distant future make our pattern of sprawling development unsupportable, it is clear that much more compact development is needed. We cannot continue to convert rural agricultural land into housing developments and raise the tax revenue to constantly recreate the infrastructure to serve these low-density bedroom communities.

A comprehensive land use plan is needed but is not likely given the hundreds of political fiefdoms and school districts that strangle attempts at regional growth coordination.

Two changes in policy should be pursued that might get through the state legislature and be signed into law by the governor. First, a state agency should be established to handle all property assessments based on market sales data. This is the only way to ensure equity across the state. Today and as long as property has been taxed in the state assessments as a percentage of market value are not only all over the map but are, by definition, in violation of the state constitution.

Second, we need to understand that there is an optimum amount of revenue to be raised via the taxation of property. Above this optimum is both inequitable and economically destructive. Below this optimum leaves in the hands of private property owners an economic benefit produced by aggregate public and private investment. The optimum amount each property owner owes to the community in taxation is whatever the tract or parcel of land held would lease for each year. Whatever improvements exist on the land parcel should be exempted from the tax base. This approach to raising revenue from property would achieve (a) a stable revenue base to pay for public goods and services; (b) reward property owners who maintain or improve property improvements; (c) provide a financial incentive for owners of land to improve land to its highest, best use as determined by market forces (and consistent with zoning, permitted densities and other government restrictions on development); and (d) eliminate the financial reasons for engaging in the speculative hoarding of land or simply ignoring land held vacant because the annual cost of doing so is nominal.