New Jersey Future Blog

Where Jobs Have Gone, Affordable Housing Hasn’t

April 3rd, 2009 by Tim Evans

- Analysis of data contained in the state Department of Community Affairs’ “Guide to Affordable Housing in New Jersey” reveals 31 municipalities* whose income-restricted affordable-housing units make up at least an estimated 10 percent of their total housing supply as of 2004. Together, these municipalities host 52 percent of the units listed on the DCA inventory, while accounting for only 15 percent of total statewide housing units. Affordable housing is thus overrepresented in these places, a group that contains most of the state’s established urban centers.

- As a group, these 31 municipalities lost 3,292 private-sector jobs between 1990 and 2006, in contrast to a statewide gain of about 300,000.

- Affordable housing is underrepresented in places that have experienced job growth. More than half of New Jersey’s increase in private-sector jobs between 1990 and 2006 — 167,000 jobs out of a total gain of about 300,000 — was concentrated in just 20 municipalities.** Removing Jersey City (something of an outlier in terms of affordable housing) from the calculation, the remaining 19 big job-gainers account for an estimated 9.8 percent of total statewide housing units in 2004, but only 6.4 percent of the DCA affordable units.

Most Large Employment Centers Are Not Accessible to Transit

The Council on Affordable Housing (COAH) is charged with implementing the New Jersey Supreme Court’s directive, expressed in its two “Mount Laurel” decisions, that each of the state’s 566 municipalities is responsible for providing its “fair share” of the regional need for low- and moderate-income housing. But some critics have argued that the current system scatters affordable housing too broadly, into places where development is not appropriate, and have suggested instead that affordable housing be steered toward the state’s older urban centers, close to jobs, public transportation and existing infrastructure.

On the surface, this argument sounds compelling. It makes sense for those of limited means to live near their jobs, or at least to live near public transportation that can take them to their jobs. For some lower-income households, owning and operating a car is a luxury. For many others, a long car commute to work from a bedroom-community suburb would take a large bite out of their total disposable income. In either case, being able to walk, bike or take transit to work mitigates otherwise tough choices about how to allocate money between transportation and other basic necessities.

But scratch the surface and the argument reveals itself to be dependent on an outdated conception of the state’s job distribution pattern. Two key implicit assumptions — that most job growth is taking place in the older urban centers where affordable housing is already concentrated, and that most jobs are near transit — do not hold up under scrutiny.

Most of the places that already host the greatest numbers of affordable units — and to which many COAH critics suggest additional units should be directed — have, in fact, been losing jobs over the past two decades. Meanwhile, most job growth has taken place in municipalities that are undersupplied with affordable housing. Putting more affordable housing in urban centers would not only fail to address the need to put lower-income households closer to employment centers; it would also exacerbate the concentration of poverty, which research has shown is a powerful obstacle to economic advancement.

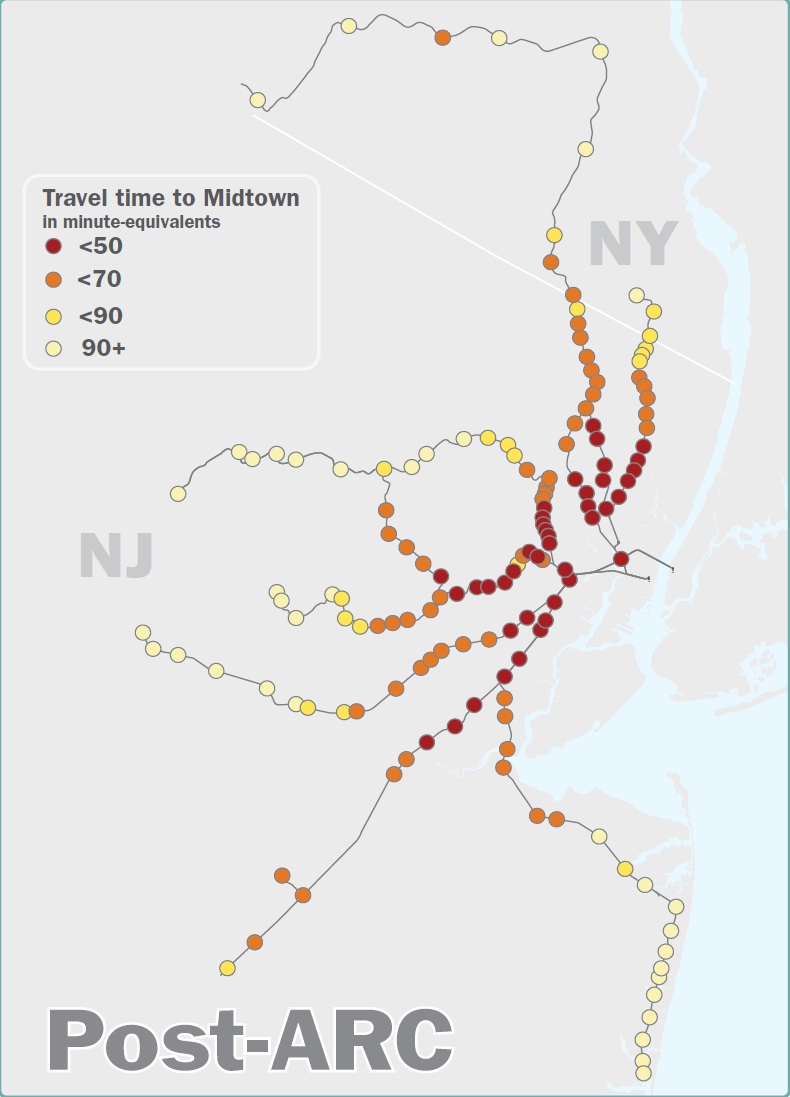

Steering affordable housing into cities and older boroughs would, in many cases, put that housing closer to the state’s public transportation network. But this largely doesn’t help, unless one’s job is in Manhattan or in job-losing Newark. Most large employment centers within the state are not accessible by transit, as evidenced by the fact that only 5 percent of intra-New Jersey commuters ride public transit to work — no better than the national rate. For every transit-friendly place like Jersey City that is actually gaining jobs, there are a dozen growing employment centers like Parsippany, Edison, Mount Laurel, Bridgewater, Cranbury, Plainsboro or Evesham Township, that are nearly impossible to get to without a car, or without taking a very long bus ride with multiple transfers. (For more on the topic of employer location relative to transit, see New Jersey Future’s 2008 report Getting to Work: Reconnecting Jobs With Transit.)

There is a legitimate case to be made for putting affordable housing where job growth is happening. Indeed, the Supreme Court expressed this very sentiment in the Mount Laurel II decision. This was also the rationale for including an employment-related growth-share requirement in the latest version of the COAH rules, in which a municipality must provide one unit of affordable housing for every 16 new jobs. But putting affordable housing near jobs does not necessarily translate to putting it in cities, where it is already over-concentrated. Instead, it will mean creating new units in some suburban communities that have not supplied nearly enough of them in the past. (For more on the imbalance between the distribution of jobs and affordable housing, see New Jersey Future’s 2003 report Realistic Opportunity? The Distribution of Affordable Housing and Jobs in New Jersey.)

If you have any questions about this issue of Future Facts, please contact Tim Evans, Research Director.

* These 31 municipalities, in descending order of estimated percent affordable, are Teterboro, Bedminster, Atlantic City, Salem, Hoboken, Newark, Bridgeton, Penns Grove, New Milford, Asbury Park, Trenton, Farmingdale, Orange, Camden, Keyport, East Orange, Wrightstown, Hampton, Pine Hill, Jersey City, West New York, Paterson, New Brunswick, Freehold, Lawnside, Upper Deerfield Twp., Burlington city, Egg Harbor City, Florham Park, Long Branch, and North Bergen.

** The 20 municipalities that gained at least 5,000 private-sector jobs between 1990 and 2006, in descending order of job gain, were Parsippany-Troy Hills Twp., Jersey City, Mount Laurel, Bridgewater, Evesham Twp., West Windsor Twp., Lakewood, Toms River, Brick Twp., Edison, Voorhees, Moorestown, Freehold borough, Warren Twp. (Somerset County), Franklin Twp. (Somerset County), Princeton borough, Princeton Twp., Woodbridge Twp., South Brunswick Twp., and Mahwah.